Psychosurgery’s troubled history of lobotomies and unregulated procedures has left modern psychiatry with strict regulations. But now, legislation designed to protect patients is actually denying those with severe mental illness access to cutting edge treatments.

Psychosurgery was developed in the 1940s after experiments revealed that a person’s behaviour could be altered by making certain incisions in the front of their brain.

The potential therapeutic benefit of the procedure was quickly recognised and gained Portugese neurologist Egas Moniz the 1949 Nobel Prize for Medicine. But the practice of psychosurgery soon diverged from what would now be considered evidence-based medical practice.

In the 1950s and early 1960s thousands of procedures were conducted in most western countries, predominately on patients hospitalised in old-fashioned asylums. These procedures were inadequately regulated and resulted in considerable harm to many patients who suffered permanent and severe side effects.

Psychosurgery almost completely died out in the 1980s and 1990s. It continued to be practiced in a handful of countries but in a much more limited way, mostly to treat severe obsessive compulsive disorder in patients who hadn’t responded to other treatments.

Since the development of deep brain stimulation approaches, surgical intervention for psychiatric disorders has undergone a revival.

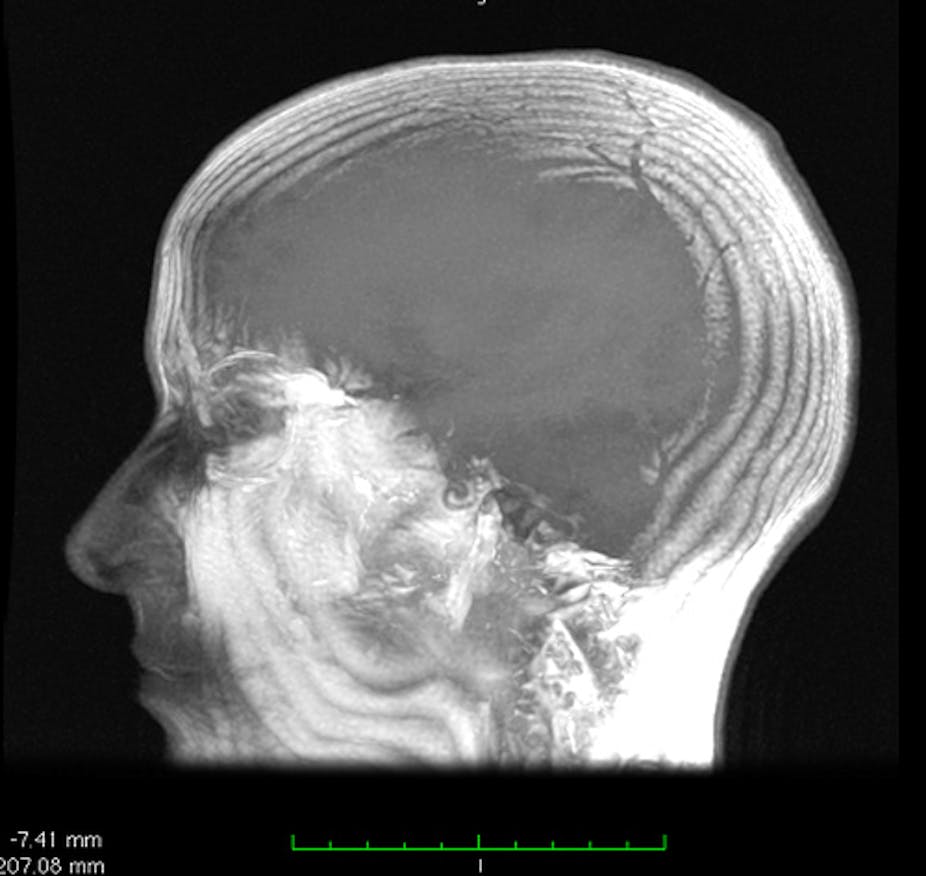

Deep brain stimulation involves the implantation of fine stimulating electrodes into small areas of the brain. The electrodes are then connected to a pacemaker-type device placed under the skin of the chest. The electrodes electrically stimulate local brain areas to try and modify brain activity that is proposed to be abnormal in a particular disorder.

Deep brain stimulation is used extensively in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease and a number of other neurological disorders, with around 85,000 patients having undergone this surgery.

In the last 10 years psychiatrists have recognised the potential of the surgery to help patients with severe psychiatric disorders like obsessive compulsive disorder and depression, especially when these disorders have not responded to standard medication treatments and psychotherapy.

Deep brain stimulation has been trialled successfully in the US, Canada and Europe for obsessive compulsive disorder and to a lesser degree, severe depression. Trials continue in these countries and the treatment has achieved limited approval for use in obsessive compulsive disorder in the US.

In most Australia states, the use of deep brain stimulation to treat psychiatric illnesses is defined as a form of psychosurgery. That means it falls under the restrictions of state-based mental health legislation and as such is banned in NSW.

If used to treat mental illness in Victoria, deep brain stimulation is heavily regulated. Operations must be approved for each patient through a body called the Victorian Psychosurgery Review Board. This body must assess whether the patient is able to consent to the treatment and that it is being provided as a ‘treatment of last resort’.

These criteria seem reasonable but because there are so many medications available to treat depression, it can take years to get to this ‘last resort’ and it can be extremely difficult to judge when this point is reached. After a number of medication trials have failed, there is no guarantee that an alternate medicine will work.

It also presents practical challenges. Applications to the board take many months (often up to a year) to fully prepare. The patient is required to attend a hearing where they are extensively questioned about their illness, their interest in the procedure and their capacity to understand the procedure. Patients almost universally find this stressful, humiliating and degrading.

The existence of this sort of paternalistic regulation is an understandable hangover from the excesses of the use of psychosurgery in the 1950s and 1960s. But we need to ask if it is still required, and what impact it has on patients who might benefit from these techniques.

Why should a consenting patient with a disorder that is defined as ‘psychiatric’ be treated any differently to one considered ‘neurological’?

A patient with Parkinson’s disease may be suffering from considerable depression and cognitive impairment (problems with thinking) as these are common in the later stages of the illness. The Parkinson’s patient can receive deep brain stimulation without any external review, potentially only days after assessment by a neurosurgeon. But a patient with depression faces a long, uncertain and stressful process to achieve the same outcome.

What about a condition like Tourette’s syndrome? This is contained in the DSM IV, the diagnostic manual used to define psychiatric illness, but surgery for it is free of review board overview in Victoria as they have deemed it not ‘psychiatric’. A patient with Tourette’s syndrome and obsessive compulsive disorder, a pair of conditions that commonly occur together, could have surgery for his or her tics without review but not for his or her obsessions.

Clearly surgical procedures for psychiatric and brain conditions should not be taken lightly. Appropriate procedures must be in place to ensure they are used appropriately, with ethical and scientific standards maintained. But these procedures should not, by definition, discriminate against a group of patients or prevent access to life-altering interventions.

The stigma associated with mental illness is finally starting to be addressed in our community. We need to consider thoughtfully how this stigma is reflected in our institutional structures. We certainly shouldn’t allow attitudes from a past era to restrict access to care in 2011.