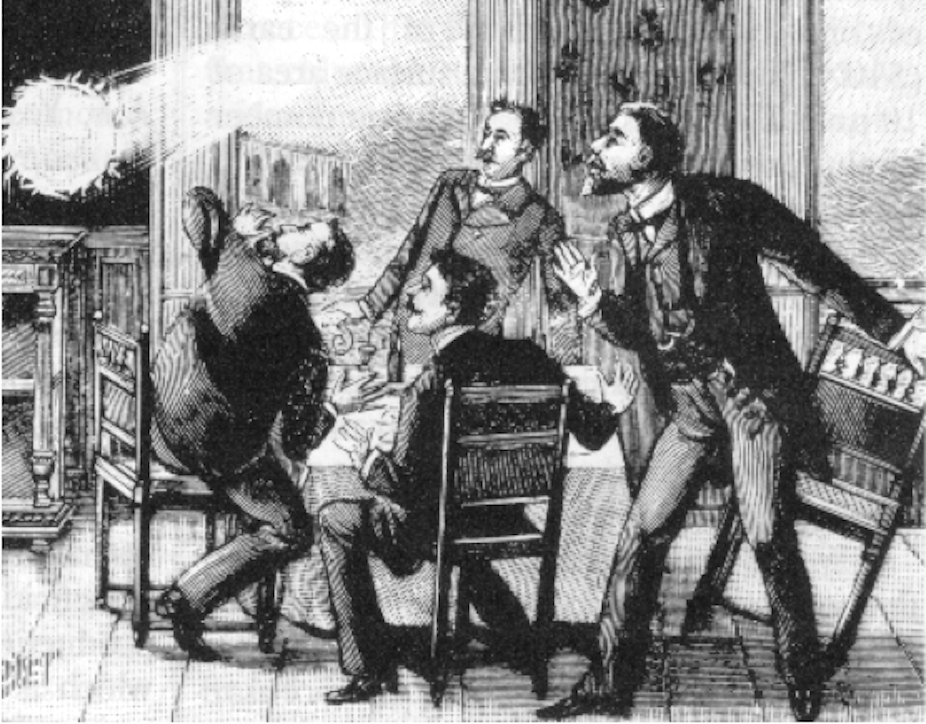

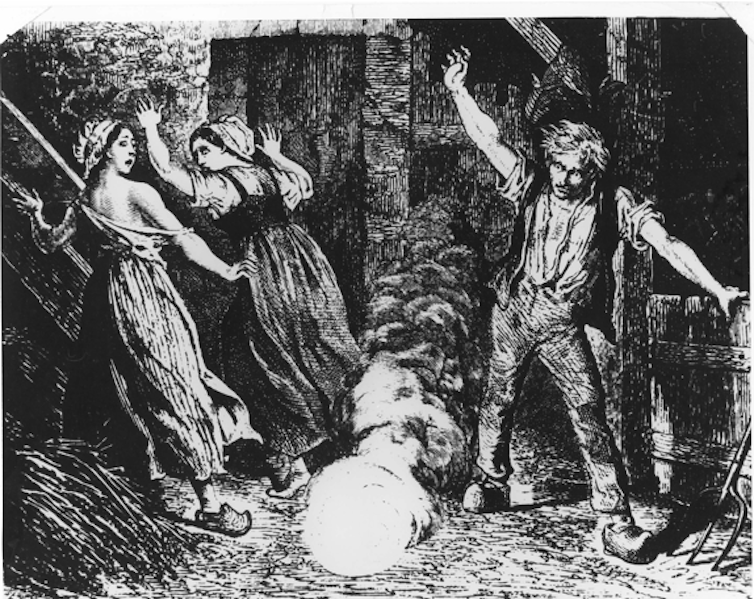

Ball lightning is one of the strangest phenomena on our planet. It’s usually seen during thunderstorms as a ball of light about the size of a grapefruit, with the intensity of roughly a 40W light bulb. It moves at about walking speed, roughly a metre above the ground, and lasts about ten seconds.

It’s been seen by hundreds of people for hundreds of years in almost every country of the world – but has remained something of a mystery. Put simply, we don’t know what it is, what provides its energy, or why it moves independently of any breeze.

But my colleagues and I have published a new paper that should shed some light on this mysterious phenomenon and bring us one step closer to understanding, definitively, what ball lightning is.

A bright history

My association with ball lightning began in the 1960s when I was working for Westinghouse Research Laboratories in Pittsburgh in the USA – working on the theory of cooling air formed from electric arcs in circuit breakers.

Next to my office was the office of physicist Martin Uman who now, having written three text books on lightning, is regarded as the world’s leading lightning scientist.

One day, over coffee, Martin mentioned that ball lightning was one of the very few phenomena we don’t understand at all, despite having been seen by hundreds, maybe thousands of people.

I replied that I thought ball lightning was just hot air produced from a lightning strike – the ball of hot air being so large that it cooled only slowly, giving it a lifetime of seconds (rather than the fraction of a second a lightning strike lasts for).

Several months later, Martin came back from one of his trips to Washington with a contract from the US Air Force for me to research ball lightning. I presume the US Air Force were interested to be able to make ball lightning and use it in the Vietnam War to scare the Viet Cong!

But there was a problem with my “hot air” theory: hot air rises and ball lightning does not generally rise. In 1969, after the contract period had expired, my colleagues and I concluded we still had no idea what ball lightning was.

Yet we wrote a paper, published in the Journal of Geophysical Research, entitled Toward a theory of Ball Lightning, in which we explained ball lightning could not just be hot air because hot air rises.

Lighting up the house

While many sightings of ball lightning have been made outdoors, it is also seen inside houses. In fact a recent French survey of 350 sightings in France found far more observations of ball lightning inside houses than outside (181 to 94).

Perhaps even scarier, ball lightning has been seen inside of aeroplanes.

Luckily, it seems the ball lightning that appears inside of houses and aeroplanes is harmless and no injuries have been reported. I’ve heard one report of ball lightning in a plane passing right through or around an air hostess as it travelled down the central aisle of the plane.

(By contrast, outdoor ball lightning has been seen to initiate very damaging lightning strikes.)

So how do these balls of lightning get inside houses and aeroplanes? And why does ball lightning almost always move?

People claim to have seen ball lightning entering a house through a closed glass window, yet subsequent examination of the window reveals no damage or even discolouration of the glass.

There have been hundreds of papers written in scientific journals speculating on these issues, variously assigning the energy source of ball lightning to nuclear energy, anti-matter, black holes, masers, microwaves … you name it.

A recent theory (besides our own) about ball lightning – published in Nature in 2000 by John Abrahamson at the University of Canterbury, New Zealand – is that ball lightning is a ball of burning dendrites (branched projections) of silicon fluff formed after a lightning strike vaporises material from the ground.

But it seems impossible that such a mechanism could cause ball lightning inside a house or aeroplane.

New and improved

The new theory about ball lightning that my colleagues and I have published is unlike any before it.

We propose ball lightning is powered by ions (charged particles) formed in the atmosphere, particularly from lightning, where columns of ions kilometres in length are produced from a lightning strike and “stepped leaders” (paths of ionised air).

In this way, ball lightning does not “pass through” closed glass windows, but is formed on the inside surface of the window by ions piling up at the outside surface of the window.

The piled up ions on the outside surface of the glass – which is an electrical insulator – increase the electric field on the inside of the glass, and can initiate ionisation – that is, the creation of charged particles.

Charges of the opposite sign to those outside on the window will be attracted to the inside of the window leaving a charged sphere of plasma free to move away from the window. This discharge is ball lightning.

Using the conventional equations for electron and ion motion in an electric field we were able to predict such a ball-like structure from a stream of ions impacting on glass.

In this way, we’ve explained (we believe) the principal mysteries of ball lightning. The energy source is ions left in the atmosphere after a lightning strike. The roughly ten-second lifetime of ball lightning can be explained as the time taken for ions to be dispersed to the ground.

The ball moves due to electrical forces from other ions that have collected on insulators, such as those that exist on the walls of rooms or aircraft. For instance, ions from the ball lightning discharge can collect on a plastic or wooden surface if the ball comes into contact with it, repelling the ball and giving the appearance of “bouncing”.

Creating ball lightning

Of course, the definitive proof of any theory is experiment. What we need is an experiment to actually reproduce ball lightning in a controlled way.

Several of the observations in aircraft have been when there was no evident thunderstorm. We postulate that the ions in this case were produced by the aircraft’s radio antenna.

If this is true, such experiments for the production of ball lightning should be possible, independent of the power sources of natural lightning, which typically generates up to 100 million volts.

If these experiments come to fruition, it is highly likely that, in the next few years, the long-standing mystery of ball lightning will be definitively solved.