Julian Barnes today won the Man Booker Prize for his novel about a childhood friendship and the fragility of memory, The Sense of an Ending. This is the fourth time he’s been nominated, and Barnes declared himself “as much relieved as I am delighted” at finally winning.

The Chair of the Judging Panel, the former head of MI5 Dame Stella Rimington, served up this year’s dose of controversy by directing the judges to focus on the “readability” of the books, ringing alarm bells in the literary world. But does this mean the prize is being “dumbed down”?

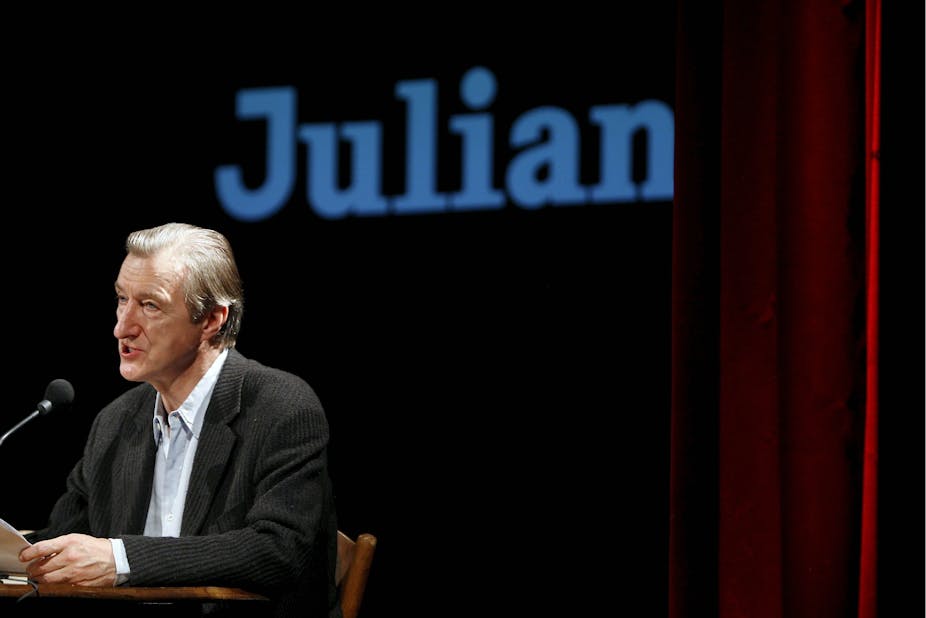

David Brooks, Associate Professor of Literature at the University of Sydney

The Booker Prize has been regarded as a publisher’s prize. To be considered you already have to be pretty much a bestseller and must be published in the UK.

The argument about readability is a storm in a teacup. One of the things a commercially successful book has to have is it has to be accessible to a large number of people. But it can also have a lot going on beyond the immediate surface. The head of the judging panel said about Barnes’ book that you want to read it a first time, then a second and a third, and that’s the sign of a very good book.

So the difference here is that Stella Rimington used the word “readability” which set the fox among the chickens, even though that has probably been a consideration since the Booker began.

It could be that the word has impinged on the elitist nature of the prize. We had a Booker panel here in Australia earlier this year, and they were very nice people, but one feeling I got was that you had to be “in the circle’” in order to be in contention, and to fit in with a certain model of literary empire. It probably helps to have a lot of friends in London. The Booker Prize is a sort of colonialist endeavour, and anything that challenges that is probably a good thing.

Robert Phiddian, Deputy Dean, School of Humanities at Flinders University

The Booker prize is a decision made by a committee locked in a room until they come to a decision.

Not too much should be made of it every year. However, the present controversy about whether it is being dumbed down in the pursuit of readability does point to something broadly real in the world of literature.

We live in a market economy where every day marketers look for ways to make it easier for us to buy and consume their products. People increasingly expect the same of books. So, while the mass market for books sucks up to us more every day, piquing our particular interests and never deliberately challenging our powers of comprehension, we lose capacity to deal with linguistic and artistic difficulty.

In my twenty-year career as a university teacher of English, Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels has gone from being from being fairly straightforward to a real effort, Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist from intriguing to impossibly weird, and poetry of any complexity has gone out the window.

It’s not that students (and the wider reading public) are getting dumber. It’s more, I think, because the culture and practice of close attention to complex artistic works is being worn down by a multimedia entertainment culture.

If the pleasure and enlightenment of these new, easier artworks is as deep as that provided by the Modernists, or even Dickens’ serpentine sentences, then this is merely progress. Difficulty can fade into history along with Morse Code and other primitive modes of communication.

Actually, though, I think we are watching the fading of a rich and powerful mode of cultural appreciation. The hyper-attention of digital media has its pleasures and purposes, but the close attention that difficult texts should not be cast off casually as a machine-age technology we no longer need.

Michelle Smith, ARC Postdoctoral Fellow at University of Melbourne

The idea of exclusivity as what makes literature worthy of awards is a fraught concept to uphold.

Why should exceptional writing be unfathomable to a large segment of the reading public? Why can’t literary merit coexist with popularity? Many canonical works commonly understood as “good literature” today (if such a thing could be defined) were wildly popular when they were originally published.

Charles Dickens finds a home in most prestigious university English departments but was eagerly read by a broad swathe of literate people in the Victorian period.

Many of his works were published serially in magazines, complete with “cliff hangers” to conclude each instalment to keep up the public thirst for “what comes next”, in the same way as today’s television series.

Though it is true that some of the most popular Victorian novels have slid into obscurity, lacking a perceived ability to speak across time, we cannot say for certain that simply because a novel is popular that it is not meritorious and will not subsequently be defined as a classic.

Indeed, the very idea of “merit” is continually shifting, which has lead to the intellectual rediscovery of books that were dismissed in the author’s lifetime.

Anne Brewster, Associate Professor, School of English, Media and Performing Arts at University of New South Wales

The announcement of the Man Booker Prize winner is often an occasion for controversy and this year’s event is no exception. I think the chair of the judging panel’s privileging of readability is regrettable as it suggests that there is a category - that of unreadable novels (presumably those that are formally difficult and challenging) - that are less suitable for the prize. What kind of message does this send to writers?

If it had been eligible, would a difficult (yet stunning) novel like Alexis Wright’s Carpentaria (which won the Miles Franklin a few years ago) have been in the running to win the Booker?

Literary prizes are one of the few avenues to promote novels of achievement that are innovative and challenging. In doing so they can encourage the broader reading public to expand their ideas of what a novel can do.

The Man Booker seems to be feeling a bit of heat over the introduction of the new Literature Prize. It broadens the pool of eligible writers - it will be open to novels published in English as distinct from the Man Booker which is for writers published in the Commonwealth and Ireland.

However both these prizes are only for books published in the UK and are therefore narrow in their conception of the field of world fiction in English.

The Commonwealth Writers Prize is much more up-to-date and inclusive - it is for fiction in English published throughout the Commonwealth and it draws its judges from all of those regions while the Booker - as far as I can see - uses only British judges. If this is the case it implies that British publishers and judges alone can be the arbiters of quality fiction in English.

Judith Sandner, Lecturer in Media, Communication & Design, University of Newcastle

The greater focus on readability does not mean that the Booker prize is being dumbed down. The fact that the dumbing down issue has been raised at all suggests that there are people involved in these sorts of hierarchical processes that have a deep investment on what’s perceived as quality work.

So from a sociological standpoint, if you think of Theodore Adorno’s ideas about the culture industry and popular culture versus high culture, and those old traditional diametrically opposed ideas about what constitute value, it’s a bit of an outdated concept I believe.

And I think that taking into consideration who is actually voicing the concerns is key when it comes to these sorts of issues because if it’s about a group of powerful elites holding on to their system of evaluation then it’s problematic.