Web 2.0 tools and mobile technologies have lowered the barriers not just for people to access the internet but to create and share content. Through open-source, collaborative programs such as wikis, the creation and distribution of information has effectively been crowdsourced.

But can this democratisation of the production of information and the expansion of networked global communities lead to action in solving real-world problems? As inventor Vinay Gupta of Hexayurt sharply puts it: “Ten years from now there will be 2 billion people with broadband internet access, but no toilet.”

Access to technology is only ever one side of the problem. The other is how people bridge the gap between the creation and sharing of knowledge and action based on that information.

Crowdsourced crisis mapping represents a significant step upon this path.

Crisis mapping is often equated to a geographic information system (GIS). GIS is a way of visually presenting, analysing and managing data and statistics, primarily through the use of maps. For example, a map could show the population density throughout Australia by using a sliding scale of colours (see image above).

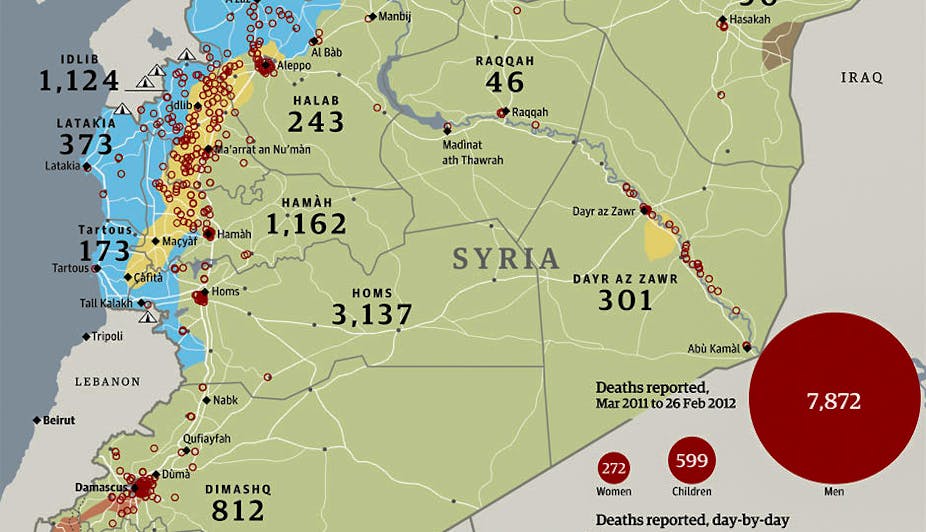

Crisis mapping goes further by embracing a broader set of tasks that provide a geolocated visualisation, allowing for filtering, categorisation and analysis of information. The Women Under Siege crowdmap from Syria, for instance, allows you to filter the information by category of attack, location and the report’s source, while checking for any available related media.

The Ushahidi (“witness” in Kiswahili) interactive mapping platform, with more than 20,000 deployments across 132 countries, ranks among the most popular crisis mapping tools.

Ushahidi was developed in the wake of the disputed Kenyan elections of 2007 as a way of reporting eye-witness accounts of violence across the country. People could text the volunteers of Ushahidi, who would display the reports through Google Maps.

In 2010, the team from Ushahidi released Crowdmap, a crowdsourced version of the platform, which allows people to “check-in” with their location and add relevant reports and information.

Crowdsourced crisis mapping aims to harness the streams of information that flow through social media to provide response organisations and other interested parties with near-real-time, categorised, and geolocated data.

The explosion of user-generated content through social media can be leveraged to assist first-aid responders and humanitarian organisations in the wake of natural disasters, crises and violent conflicts, or even (more tongue-in-cheek) a zombie apocalypse.

Automatic processes can be applied to extract, filter and structure content from social media – tasks that are currently performed by human volunteers.

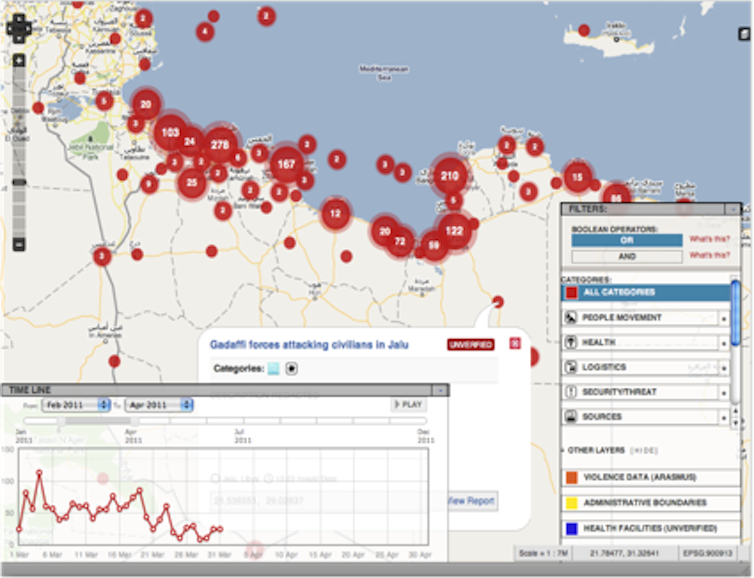

In the 2011 Libya Crisis Map, a joint initiative of the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) and the Standby Task Force, online volunteers would work in shifts to monitor social media sites and extract relevant information to manually create reports.

Other teams would provide GIS coordinates, perform categorisation checks and seek to verify the information – a highly complex task when it comes to crowdsourced information.

The advantages of crowdsourcing are becoming apparent in other areas. Software engineer and political activist Tarik Nesh-Nash launched an on-line platform where citizens would post comments and vote for articles of the new Moroccan constitution, attracting 200,000 visits in a few weeks.

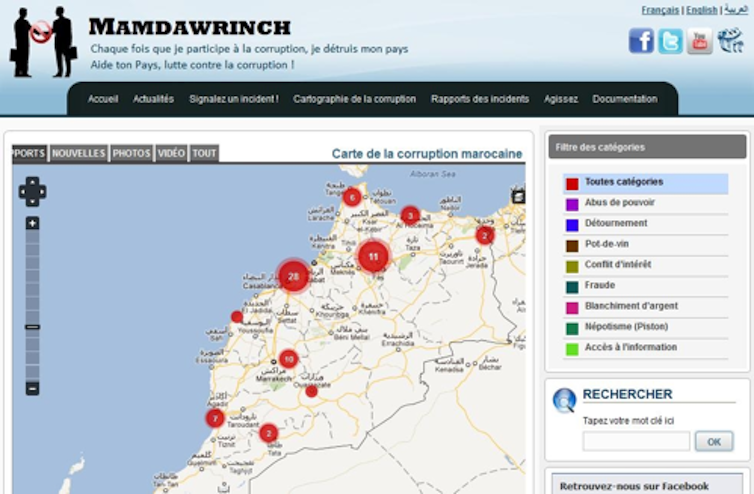

He has partnered with Transparency Morocco to set up Mamdawrinch (see image below), inspired by the Indian site I Paid A Bribe – a site dedicated to tracking, verifying and mapping corruption incidents across the country.

But there is still plenty of room to foster further cooperation between computer scientists, human rights activists and digital citizens. The social web and the “web of data” have to become more inter-connected and usable in the deployment processes.

The World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) Open Linking Data Community Project is a collective effort to extract structured information from Wikipedia and to make it more readily available and reusable.

The W3C is also working on a framework for sharing knowledge and emergency management operating systems, with the aim of helping to classify and manage the content of reports. But, this has yet to be tested through the reality of crisis mapping deployment.

Digital neighbourhood actions can operate under extremely difficult scenarios: collapsed states, countries undergoing transitional justice and development of democratic institutions.

In sensitive environments such as the Libya Crisis Map or, more recently, the Syria Tracker, building a set of trusted information sources may involve major security issues. It can seriously compromise the safety of the people who originally published information on social media.

The crisis mapping community is currently developing general standards and the ethical, privacy and security issues that need to be carefully addressed in each case that crowdsourced crisis mapping is deployed.

To protect and maintain the ability of human-rights activists to operate in this digital space, a renewed framework, or “relational law”, is required that can bring technology, networked governance and legal protection together.

One thing’s for sure – there will never be a shortage of crises nor, hopefully, enough people willing to help solve them.