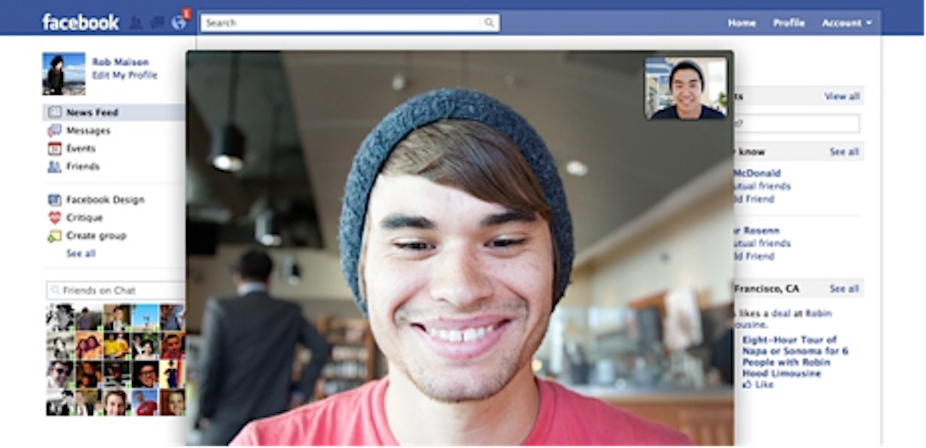

Last week, Facebook introduced one-to-one video calling. With a claimed userbase of 750 million accounts, the potential for ubiquitous video calling seems obvious.

But, will it work?

Of all post-industrial revolution communication technologies, video calling has had the rockiest path to usability and popularity.

Could Facebook have the edge that has eluded prior services?

Seeing as you ask

The concept of seeing and hearing a distant interlocutor was sparked in the public imagination soon after Alexander Graham Bell patented the telephone in 1876 and Charles Emile Reynaud’s Praxinoscope was projecting moving pictures in 1877.

Just one year later, there were a flurry of fictional depictions of this idea by French futurists: George du Maurier’s “Telephonoscope” (1878), Albert Robida’s “Telephonoscope” (1883), Jules and Michel Verne’s “Phonotelephote” (1889), Georges Méliès’ “Long Distance Wireless Photography” (1908), and an anonymous postcard depicting “Correspondence Cinema” (1910) (see picture below).

In 1930, the same year as a German comic (The End of the World) depicted mobile video calling (see image above), the New York Daily Mirror reported that US telecommunication giant AT&T’s president, Walter Gifford, held a live two-way video call with researchers in a nearby Bell Labs building.

The German Post Office ran the world’s first public video calling service from 1936 to 1940. AT&T debuted its Mod I Picturephone at the 1964 New York World’s Fair and later set up Picturephone booths in three US cities.

But the three-minute call cost of $16 proved unpopular, and cutting rates by 50% the next year did not help.

Scheduling issues

Cost aside, the biggest problem with the public booths was the social inconvenience of having to schedule the call well ahead of time and, of course, the special trip to a specific location.

Undeterred, AT&T released the Mod II commercial Picturephone service in 1970.

Although it was now available in the home, the cost was still outrageous: $160 a month subscription and an $18 per minute connection fee at both ends.

Recent failures

This pattern has been repeated with videophones up until as recently as 2009. AT&T failed again with its 1992 Videophone.

In 2005, the Vialta Beamer (see video below) and the Amstrad em@iler E3 videophones were discontinued, and the Verizon Hub was a failure upon launch in 2009.

All these services required subscriptions for proprietary single-purpose hardware, lock-in to a particular service, and started operating with little-to-no user base.

Add to this huge costs and generally acceptable (but certainly not high-quality) audio-video, and some of the reasons for failure become quite clear.

That said, video calling clearly does exist now on computer-based devices – Skype being the obvious example.

Free and easy

Around the same time as AT&T debuted the Picturephone in 1964, two far more utilitarian technologies developed and began to converge: the internet and personal computers.

This paved the way for multiple applications running on cheap general-purpose hardware based on the same infrastructure, removing the awareness of specialist technical knowledge required to use some of the older videophones.

Internet Protocol (IP) video calling was born in the late 1980s and soon lead to a profusion of software+service video calling providers in the 1990s.

CU-SeeMe (see image below), PalTalk, and SightSpeed offered subscriptions far cheaper than videophones.

Costs plummeted still further in the mid-2000s onwards, as all major Instant Messaging (IM), Voice Over Internet Protocol (VoIP), and some web-based services began to offer free video calling.

Still, despite being cheaper or now free, and even with userbases of several million users, IM, VoIP, and web-based video calling services have always faced – and continue to face – barriers to having the critical mass necessary for ubiquity.

Seeing is deceiving

The first barrier is purely quantitative. Users need to be drawn to a service, often by one person asking another to join. But “joining fatigue” soon sets in, especially when people use a range of difference services.

There are, of course, aggregation applications that allow users to connect to multiple IM, VoIP, and social media sites, but despite some standardisation of video calling protocols in general, several of the biggest services have incompatible video calling signals, so the aggregators don’t work for video calling.

Facebook clearly has an edge here by virtue of having existed well before introducing its video calling service. As said above, Facebook claims an enormous userbase of 750 million accounts.

Of course, the actual number of potential Facebook video calling users is likely to be significantly lower. But these few million people are already on Facebook, as are many of their contacts, and Facebook has a combination of high utility and easy usability that lowers the barrier to entry.

What’s more, if users don’t already have video calling-capable devices, the sudden availability of large cohort of people to video calling with may be just the push needed to overcome the psychological barrier to buying a cheap add-on camera or perhaps buying a new device.

Facebook’s real edge, though, may be qualitative. The second barrier to ubiquity is that video calling demands people have the place, time, and desire to devote most of their attention to the audio and video of one another.

Facebook does this remarkably well. The company encourages us to continually update or create our profiles, our contacts do the same, we all connect and, like magic, we develop a very rich, persistent knowledge of each other.

This knowledge melds physical and online life, and cues us to return. Further, notifications of new comments and events by email and SMS reach out of Facebook and draw us back. This goes beyond the basic sense of presence awareness, whereby you’re aware of those “around” you, and vice versa, to magnifying a persistent and pervasive sense of the movements and experiences of your social network.

Real-time chat, introduced to Facebook in 2008, added a new chronological dimension to this presence-awareness, and, of course gave people another reason to log on and stay on Facebook for longer, and setting the stage for video calling.

Hello? Is there anybody out there?

On Facebook, the opportunities for spontaneous video calling are extremely high – much higher than for IM, VoIP, or web-based services alone – because we are cued to be responsive to the presence of others.

Particularly for those people using Facebook in non-work periods and environments, Facebook video calling eases the scheduling difficulties that are the common social barrier to video calling.

Because many of our friends, family, and acquaintance have Facebook accounts already, and may be “on” simultaneously, our sense of Facebook’s social infrastructure comes to resembles that of the telephone: we are likely to be able to contact just the person we want, just when we want to, without much preparation.

Until Google+ gains significantly more users, this, more than the one-on-one versus group capability, will be the main difference between Facebook video calling and Google’s new multi-person Hangouts (announced just days before Facebook’s offering). That being said, perhaps group video calling will turn out to be the real key to video calling ubiquity.

What you see is what you get

But not even the mighty Facebook can change the physical conditions in which we have to do video calling. Seeing and being seen in a video call is markedly more intimate that hearing and being heard in voice chat alone.

Indeed, it may be that video calling simply gives too much away to ever become as ubiquitous as the more constrained voice chat, email or textual chat.

On the other hand, as rich as it is, video calling also still feels limiting for all sorts of interactions with intimates or colleagues.

Video calling may end up being a stepping-stone on the path to multi-sense immersive telepresence, rather than an endpoint in and of itself.

Until then, we’ll be seeing more of one another – perhaps more than we ever bargained for.