What do Shane Warne, Kylie Minogue, Muammar Gaddafi, Mike Tyson and Kermit the Frog have in common?

Believe it or not, all have been awarded university doctorates.

Yep, that’s right, Dr Warney. Southampton Solent University in the United Kingdom awarded him the honour for services to cricket. On receiving the doctorate, Warne proclaimed, “I am officially the spin doctor now.”

A rising tide of celebrity doctorates suggests they may be the latest must-have accessory. In fact, many famous names have received honorary doctorates, including sports stars (Muhammad Ali, humanities); administrators (Joseph Blatter, FIFA president: arts); presidents (Bill Clinton, public service); actors (Clint Eastwood, fine arts); and musicians (Billy Joel, music).

While Drs Tyson and Ali may be famous students of the “sweet science” of boxing, their doctorates weren’t a product of academic prowess. These are not the kind of doctorates you get from years of hard slog to become an expert in your chosen field.

One of the more outrageous examples of honorary doctorates was highlighted earlier this year. Non-governmental organisation (NGO) Change.org started an online petition calling on the nine universities that had awarded former Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi an honorary PhD to revoke the honour. The call sparked debate among academics and researchers about what honorary doctorates symbolise, why they are awarded, and to whom.

This debate was re-ignited earlier this month when pop-star Dannii Minogue received an honorary doctorate in media for “services to the entertainment industry” from Solent University in England’s South East (obviously a chronic offender). This, hot on the heels of sister Kylie receiving an honorary doctorate for services to breast cancer.

When Dannii stated she was “shocked” to receive the award, the Twitter PhD community responded with a similar amount of incredulity.

Many PhD holders described the years they spent in their stressed out, lowly-paid slog that ended up with those three letters after their name. Some asked if the Minogue sisters would now be prepared to accept an academic salary to go with their doctorates. (One asked whether Dannii’s honorary doctorate meant that she was entitled to be an honorary pop star.)

From a university’s perspective, awarding honorary doctorates can be a valid way of recognising outstanding achievement in a particular field, or recognition for service. But does the awarding of celebrity PhDs undermine the academic reputation of a university or its graduates?

Most Australian universities have published policies on awarding honorary doctorates. These typically refer to academic eminence and services to a university or wider community. Some universities have decided not to award honorary doctorates. MIT, Cornell and Stanford are part of this club, as is UCLA, which awards its own UCLA Medal instead of honorary degrees.

Even with these guidelines, why do many universities drop standards of academic performance for some, while the system is so tightly regulated for most? It’s ironic that Danni Minogue was awarded her doctorate on the same day that University of Queensland Vice-chancellor Paul Greenfield resigned after admitting he accepted the enrolment of an under-qualified relative.

Of course, there are times when honorary doctorates are well deserved. Few people would argue with Nelson Mandela’s six honorary doctorates for services to humanity, including one from the University of South Australia.

And there are actually a few famous musicians who have earned a real PhD. Dr Brian May of rock group Queen fame – not content with being named by Rolling Stone as one of the 100 greatest guitarists of all time – recently finished a PhD in astrophysics.

One thing that irks people with a real PhD is when honorary recipients call themselves “doctor”. This is generally discouraged, but there are notable examples of people who have embraced the use of the title.

Former governor general Peter Hollingworth was controversially very fond of calling himself Dr Hollingworth.

More recently, the new Director-General of NSW Health, Mary Foley, has begun referring to herself as Dr Foley since receiving an honorary doctor of letters from the University of Western Sydney (UWS), a move that’s sure to engender respect in the many real doctors working in the system she leads.

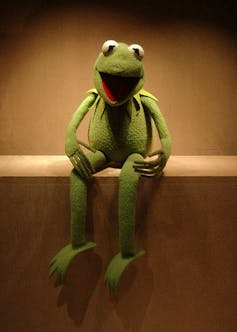

Maybe it’s best to leave the final word on honorary doctorates to a fictional character. Kermit the Frog received an honorary doctorate of amphibious letters from Long Island University, in recognition for services to environmentalism through his song “It’s not easy being green”. In his acceptance speech, Dr Frog said:

“To tell you the truth, I never even knew there was such a thing as ‘Amphibious’ Letters. After all those years on Sesame Street, you’d think I’d know my alphabet. It just goes to show that you can teach an old frog new tricks”.

Is it time to abandon the honorary PhD? Share your comments below