IDEAS AND OWNERSHIP: The concept of protecting ideas and innovation by legal means dates back to antiquity. But in the age of the internet and multinational business models, many of the existing laws are under strain, their suitability and ultimate purpose called into question.

Bruce Arnold kicks off a new series on The Conversation looking at where we are, where we were and where we’re going with regards to patents, copyright, trademarks and IP.

It’s become a cliché that most Australians are part of an information society or information economy. In fact, we’re all part of an intellectual property society. Intellectual property (IP) affects what we consume and what we create. It also affects when we’re born and when we die, given modern medicine is founded on pharmaceuticals and devices that are encouraged by intellectual property law.

This article offers a snapshot, quick and irreverent, of what IP is, why it’s controversial, and the difference between some key terms.

In essence, IP law provides rights owners with the power to stop unauthorised copying. That power is for a finite period of years. At the end of the period (which can be as little as five years) the owners’ rights evaporate.

IP involves a tension between society’s respect for individuals as creators, incentives for investment (getting a life-saving drug into the market costs hundreds of millions of dollars) and the benefits for both individual consumers and society resulting from easy access to innovation.

Put simply, we want to encourage our authors, artists and researchers to produce good things (and to make money for investors such as the superannuation funds that will pay for our old age). We also don’t want to lock up creativity so that it’s too expensive or too secret for all of us to benefit from sharing.

Australia’s part of a global economy, so we also need to comply with international agreements, some of which (contrary to mythology) place public health over the rights of multinational tobacco companies.

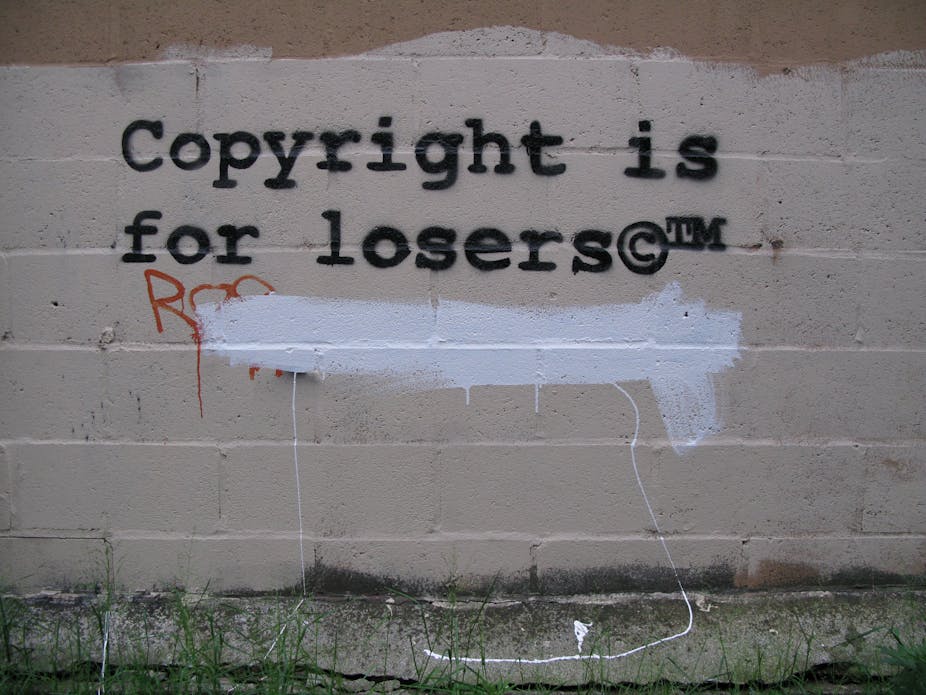

Some people disagree about the balance; others simply assert we can disregard IP in the hope that people will play nicely.

Copyright

Everyone is a creator when they write a letter or an email, take a photo, post a blog or do a sketch to amuse the kids. The good news is that their creativity’s protected by the Copyright Act 1968. The bad news is that there’s a commercial difference between my scribble and a masterpiece by David Malouf or Peter Porter, your sketch and a Rothko canvas.

The good news is that, irrespective of commercial rewards, copyright law protects all, offers an incentive for creativity by all. The same law allows non-commercial copying by scholars, journalists and others, balancing individual and community interests.

Copyright encompasses music, film, broadcasts, text, software, architecture and the graphic arts. It’s different to trademarks, patents and designs.

We are immersed in trademarks, signs that function as indicators of quality and of the consumer’s taste or affinity. Trademark owners can use the Trade Marks Act 1995 to stop a competitor from using their sign to falsely identify a product of service.

That sign might be words, or a logo (the McDonald’s “Golden Arches” and other icons damned by Naomi Klein). It might be a unique sound (the “Dolmio Waltz” or “Ah McCain” ding). It could even be a scent that uniquely identifies a particular product.

Trademarks and patents

Trademarks represent the most in-your-face aspect of contemporary capitalism. They also indicate trust and safety. It matters if your medication is really from Pfizer (with an authentic mark) or a concoction of rat faeces and plaster that uses a counterfeit mark.

Patents – the most contentious form of IP for many academics – protect inventions. The inventions covered by the Patents Act 1990 include car parts, pharmaceuticals, toys, devices such as the iPad, paints, ploughs and even business methods.

Some of those inventions are trivial and soon forgotten. Others are fundamental and deservedly provide the inventor and investors with large rewards. Think of MRI scanners and stents in medicine, ABS brakes on cars, the chips found in most electronic devices.

Patent law deals with invention, not discovery. It is concerned with originality. After a maximum of 25 years the protection ceases: anyone is free to copy the invention (piggyback on the inventor’s creativity and hard work) without payment or permission.

As with copyright, patent law involves a balance between respect, incentives and social needs. It is contentious because some people consider the balance is overly weighted towards large corporate interests.

Examples of this would be pharmaceuticals being too expensive, speculators engaging in “patent trolling” or the traditional knowledge of indigenous peoples being appropriated through biocolonialism . Others respond that the problem is with global economic disparities rather than patents per se.

Looks matter

Not all IP is about billions or biopolitics. Ever sighed over a Fink jug or a “to-die-for” textile? Copyright law coexists with the Designs Act 2003, which gives designers short (five years) protection regarding the appearance of a manufactured product.

That appearance might be shape – the sensuous curves of a jug – or it might be the pattern of a textile (Marimekko or Ken Done).

What if you develop a blue rose, a crispy lettuce, disease-resistant wheat, an extraordinarily tasty melon or a fast-growing tree? Your innovation – again potentially involving major investment, effort, skills and frustration – can gain short-term protection through the Plant Breeders’ Rights Act 1994. Other similarly specialised law protects creativity such as the layout of computer chips.

IP is ultimately about power, money, innovation and regard for individuals who struggle to add to the sum of knowledge and cultures. Academia needs to make decisions about its own IP on an informed rather than emotive basis, and work with other interests in developing equitable law and practice.

IP is not just something that belongs to the vice-chancellor or Bill Gates: it’s about us.

Further articles in this series will be published on The Conversation in the coming week.