The economic troubles of Italy are largely homegrown. Some might argue that they have been made worse by the fiscal austerity measures adopted under pressure from the European Union. But the truth is that, Europe or not, three decades of fiscal profligacy eventually had to come to an end. The landing could not possibly be soft.

If problems are homegrown, then their solution should also be homegrown. In this regard, the elections held last week-end could have been a good starting point: new parliament, new government, and a new push towards long-term, pro-growth reforms.

But this does not seem to have been the case. First of all, throughout the campaign, the issue of long-term growth has been overshadowed by the debate on fiscal austerity. Parties have talked a lot about cutting taxes and balancing the budget, but they have not said much about what should be done to re-launch growth after twenty years of stagnation.

Second, the polls yielded a highly fragmented parliament which is unlikely to generate the type of solid and cohesive government required to undertake long-term economic reforms.

No party or coalition has a majority in both Houses (House of Representatives and Senate). In the House of Representatives, the centre-left coalition led by the Democratic Party (PD) won by a very small margin over the centre-right coalition led by the People of Freedom Party (PDL). Because of the Italian electoral system, even such a small margin translates into a significant majority in the number of elected representatives.

In the Senate, the situation is much more complicated. The total number of senators is 315: the PD and its allied gained 119 seats, the PDL and its allied 117 seats, the Five Star movement 54 seats, and Civic Choice 18 seats. Even if seven seats still remain to be assigned, it is already clear that none of the parties/coalitions can reach the majority quorum of 158.

Winners and losers

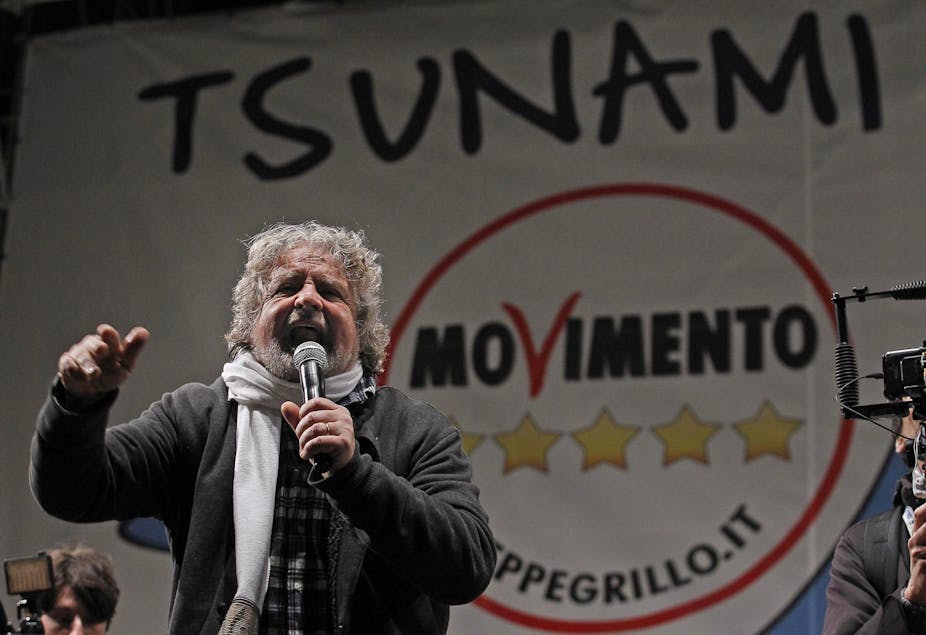

There are two main winners in this election. One is certainly the new Five Star movement, led by former comedian Beppe Grillo. Five Star is an anti-politics movement whose campaign was based on a rather populist platform.

Five Star gathered the “vote of protest” of most Italian citizens dissatisfied with the political class. It achieved a remarkable 25% of votes in the House of Representatives (a bit less in the Senate), which makes it the largest single party in the legislature.

The second winner is Silvio Berlusconi, the leader of PDL. Thrown out of office 15 months ago and currently on trial for various charges, including a sex scandal, Berlusconi led his centre-right coalition to an amazing climb back.

No more than two months ago, PDL lagged 20 percentage points behind the PD in the opinion polls. The electoral results today say that the PD-led coalition and the PDL-led coalition are both around 30%, separated by a mere 0.5% in the House of Representatives (1% in the Senate).

The main loser is instead PD, which lost the large advantage it had over both PDL and Five Stars in just a couple of months. For one thing, the leadership of PD was unable to communicate effectively with a large segment of moderate electorate. For another, PD remained trapped between the strong anti-taxation stance taken by Berlusconi and the general sentiment of distrust towards politics, which drove the success of Five Star.

The second loser is outgoing Prime Minister Mario Monti. His Civic Choice movement, allied with a couple of small centrist parties, did not go beyond 10% of votes in both Houses, which makes it almost irrelevant in the coalition game that will be played by PD, PDL, and Five Stars.

Monti was appointed Prime Minister in November 2011, when it became evident that Berlusconi’s government was unable to respond to the debt crisis. He headed a technical government that undertook tough measures of fiscal austerity.

While at that time there was no alternative to fiscal austerity, Monti should have also started an ambitious plan of reforms. Unfortunately, this did not happen and the austerity measures significantly worsened the recession.

During the electoral campaign, Monti somewhat loosened his fiscal stance, promising to lower certain taxes and to start reforms, but evidently Italian voters were not inclined to give him a second chance.

Someone might read Monti’s poor showing as a vote against the European Union. The Five Star movement, which loudly demands a renegotiation of Italy’s agreements with Europe, might have also benefited from a growing anti-European sentiment within the electorate.

However, more than a rejection of the European Union, the vote might signal that citizens have understood what parties still fail to grasp: it is the lack of economic growth that makes fiscal austerity necessary. Re-start growth, and draconian fiscal measures will no longer be needed.

Playing the coalition game

Because of its majority in the House of Representatives, the PD is still the obvious candidate to form a government. Numbers are such that some sort of agreement with either PDL or Five Stars will be needed in the Senate.

The leader of PD, Pier Luigi Bersani, is probably orientated towards striking a deal with Five Star. The most likely scenario is one where PD forms a minority government (together with the other small parties in the centre-left coalition) and Five Star provides some conditional external support.

It is hard to say what kind of economic policy a government like this would be able to implement.

PD’s policy platform includes a set of tax cuts for lower-income households and an increase of deductions on taxes on reinvested earnings. To offset the decrease in tax revenues, PD proposes to cut transfers and government consumption and to raise extra-revenues from the sale of public assets and the fight against tax evasion.

In principle, these are all measures that Five Star might be willing to support. The central question is what Five Star will ask in return. The answer here is particularly difficult because the movement avoided any debate with other parties/coalitions during this campaign, and its published policy document does not provide much detail on economic policy.

Making the public administration more transparent and less expensive is a recurrent theme in the rhetoric of Five Star, and it is something the PD should be prepared to do. But some of the other ideas of Five Star in the area of labour market reforms or European integration might be difficult for the PD to digest.

Moreover, it is unclear to what extent a protest and anti-politics movement like Five Star is willing to support a PD-led government. In fact, Five Star has probably more to gain by staying in opposition, at least for now.

The alternative for PD is an alliance with the centre-right. Paradoxically, some common ground for this coalition could be found in the policy programme of PDL, which includes a large fiscal stimulus package with comprehensive tax cuts, an increase in public investment, a reorganisation of tax expenditures, stronger action against tax evasion and capital flights, and an aggressive public assets sale plan.

In a post-election interview, Berlusconi indeed suggested that PDL might be willing to cooperate with PD to form a large coalition government. But the two parties have been engaged in fierce competition for 20 years, their leaders have attacked each other violently, often on personal grounds. The wounds caused by this conflict are too fresh and too large to be quickly healed. Hence, not surprisingly, Bersani promptly rejected Berlusconi’s offer.

If the attempt of the PD to form a government were to fail, then there would be only one possible way forward: new elections. In itself, the risk of having to put the country through another long campaign, in these economic conditions, should be a strong-enough incentive for parties to find an agreement.

But alas, the present economic and political situation of Italy suggests that, in the past, the good of the country got often lost in the subtleties of the political game. Can we expect anything different this time?