The proposed Browse Liquefied Natural Gas Hub at James Price Point (known locally as Walmadany), 50km north of Broome, has created one of the most fiercely fought environmental and indigenous battles currently occurring in Australia. Despite the existence of alternative brown field sites (such as Karratha), the State Government prefers James Price Point even though it is likely to be a far more expensive option (an estimated $15 billion) for joint venture partners Woodside, BP, BHP, Shell and Mitsui/Mistubishi, and tax payers.

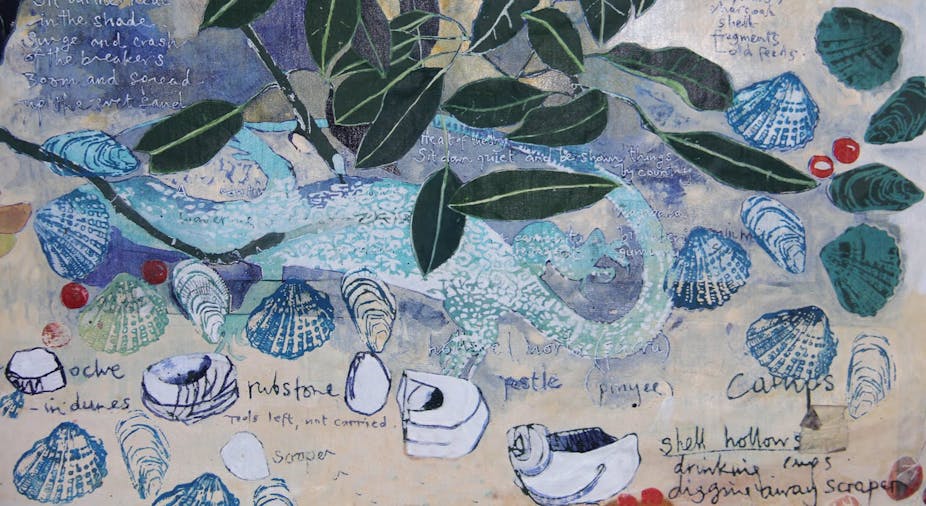

The James Price Point option is also far more pristine, biodiverse and ecologically significant, with a rich indigenous connection to country. The area is abundant with indigenous songcycle pathways, burial grounds, the Lurujarri Heritage Trail, calving Humpback whales, dugongs, dolphins, abundant fishes, coral reefs, seagrass, remnant rainforest, dinosaur trackways and breeding bilbies. The area is so ecologically and culturally rich that it was recommended for National Park protection by the Australian Academy of Sciences and the National Parks Board of WA in 1962; the WA Environmental Protection Authority in 1977 and 1993; the WA Department of Conservation and Land Management in 1991; the Broome Shire, Department of Land Administration and WA State Cabinet in 2000; and the Broome Planning Steering Committee in 2005.

This is all at odds with the state premier Colin Barnett’s description of the area as an “unremarkable” piece of coastline.

Despite all the recommendations for protection, James Price is the state government’s preferred option. It therefore requires an environmental impact assessment of whether the gas hub could proceed without significant, severe and long lasting impacts on the local environment.

The WA Environmental Protection Authority (EPA) recently completed an initial assessment. A further assessment is due from the Federal Environment Minister at the end of the year. The WA EPA based their assessment on the Strategic Assessment Report (SAR) prepared by the state government for the project, giving the project the green light.

As the proposed gas hub is one of the largest industrial projects in Australia’s history and will become the largest gas hub in the world, one would expect the environmental impact assessment to be well considered, comprehensive, robust and based on sound science. Unfortunately the EPA’s assessment fell far below these expectations.

Major issues occurred in the assessment process itself. The state government recognised that - due to the scale and complexity of the project - they’d need a high level of confidence in the science underpinning the SAR. They recommended establishing a peer review process. This didn’t happen: only the minority of the science was scrutinised and only when major inadequacies were revealed by independent and citizen scientists.

This leaves little confidence and much uncertainty in the quality of the SAR’s science on which the EPA based their assessment. When the assessment was undertaken, four out of five EPA board members had to be excluded due to conflicts of interest, leaving a “quorum” of one. As three of these conflicted members were excluded only months before the completion of the five year assessment, there was ample opportunity for their conflicts to influence the process.

Despite these procedural issues, how did the EPA justify impacts to the significant ecological communities and species of James Price Point? For brevity I will focus on two of the most significant ecological features of the area.

One of the most striking and significant ecological features of the James Price Point area is the monsoon vine thicket that occurs behind the coastal dunes. This little-studied remnant rainforest is incredibly diverse, containing 25% of all plant species from the Dampier Peninsula and up to 70 species of ants. This rainforest also contains one of the highest densities of bush tucker and medicinal plants in Australia and is therefore critically significant to the local indigenous people. Poor fire management, weeds and land clearing have led to fragmentation and declines in these communities. The communities are currently under assessment for federal listing as a threatened ecological community.

The James Price Point area contains one of the peninsula’s largest and most diverse vine thicket patches (19% of all Dampier Peninsula vine thicket). The gas hub will lead to a direct clearing of 132 ha of this vine thicket (or 5% of all peninsula vine thicket). Wider impacts are highly likely, due to fragmentation and major changes to the groundwater which sustains it.

On two previous occasions (1990 and 1991) the EPA recommended that no clearing of monsoonal vine thicket should occur due to its ecological significance. Yet for the gas hub, the EPA have allowed 132 ha to be cleared with no scientific justification of why this is not considered a significant impact or why their opinion has changed.

Out in the ocean, extending from Broome north to Camden Sound, is the calving ground of the world’s largest humpback whale population. Whales migrate up from the Antarctic to calve, rest and play in these waters, part of the most pristine tropical waters on the planet. Into this calving ground, the gas hub will impose a ~3km long jetty, a ~7km dredged channel and shipping traffic of ~1300 a year. Impacts from the port facilities (e.g. dredging, smothering etc.) will create what the SAR calls a “marine deadzone”, 50 km2 in size.

The EPA believe the hub will not cause significant impacts to whales. This belief is based largely on the SAR’s whale research. After reviewing the same whale research, the Cetacean Research Group at Murdoch University concluded that they had “very little confidence in the scientific integrity of the report and this is evidenced by the unfounded conclusions reached within”.

Among its weaknesses, the SAR suggests the James Price Point area is not part of the main calving ground, in direct conflict with the Federal Department of Environment’s definition and other scientific reports largely overlooked by the EPA.

The SAR also suggests that only a small number of whales (1000 in 2012) pass within 8km of the coastline where the major impacts will occur. Yet a community science whale survey currently underway has shown that these estimates are far too low, with estimates of over 8600 more realistic.

These are only two examples of important ecological features threatened by the gas hub yet not adequately represented by the SAR or assessed by the EPA. The SAR has also been shown to be inadequate for dolphins, dinosaur trackways, turtle nesting, bilbies, dredging and social impacts. Decisions regarding large scale industrial projects should be well considered and based on sound science: this has not occurred for the James Price Point Gas Hub.

There are alternatives to the James Price Point option, such as piping the gas and oil down to existing facilities in Karratha. These are cheaper for the companies and tax payer, and will create fewer environmental and cultural impacts. This seems like a win-win situation for all.

Unfortunately, James Price Point is the preferred option of the state government as it’s the thin edge of the wedge, providing port facilities and energy sources for the further industrialisation of the Kimberley. If this hub goes ahead, the environmental and cultural repercussions will not just be felt at Walmadany but throughout the whole of the Kimberley for decades to come.