Scientists say they have developed a way to use a patient’s own stem cells to build fully functional organs in a laboratory, in a potential solution to the global donor shortage crisis.

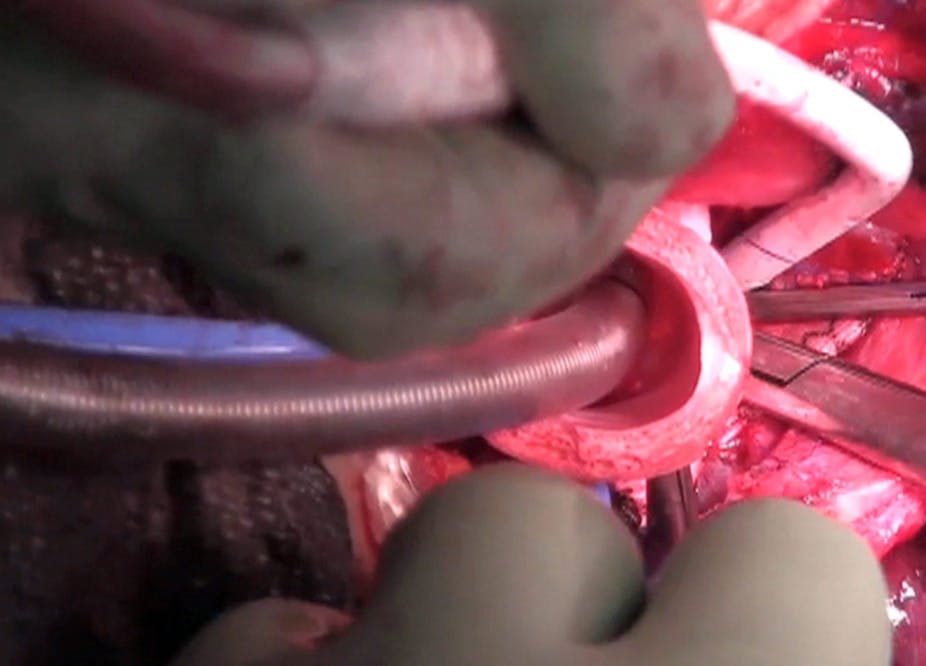

The technique involves creating a three-dimensional biological scaffold made with human or animal tissue then inserting the patient’s stem cells to regenerate and transplant organs. It requires no human donors, has no problems with rejection, and has no need for immunosuppressive drugs, say the researchers in a paper published in The Lancet.

The lead author, Paolo Macchiarini, from the Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden, said that the approach “has already been used successfully for the repair and reconstruction of several complex tissues such as the trachea, oesophagus, and skeletal muscle in animal models and human beings, and guided by appropriate scientific and ethical oversight, could serve as a platform for the engineering of whole organs and other tissues, and might become a viable and practical future therapeutic approach to meet demand after organ failure”.

Dr Macchiarini said that the technique could help to address the crisis in whole-organ donor supply. In Australia, the average waiting time for a transplant is about four years, but it is not uncommon for patients to wait up to seven years. On average one person dies each week while waiting for a transplant. Patients who are fortunate enough to receive a donor organ still face life-long expensive and potentially dangerous immunosuppressive therapy.

Identifying the best cell sources for different organs, as well as the ideal scaffold material, were among the challenges that would need to be addressed before widespread clinical use could be adopted, Dr Macchiarini said.

In the paper, the authors warn that there are numerous ethical issues raised by the new technology. “The pressure to advance this technique, driven by demand, the race for prestige, and the potential for huge profits, mandates an early commitment be made to establish the safety of various strategies … particularly when there are so many potential patients and doctors who are desperate for any remedy that offers hope.”

Wendy Rogers, a Professor of Clinical Ethics in the Department of Philosophy and the Australian School of Advanced Medicine at Macquarie University, said that the promise of stem-cell engineered whole organs was attractive because it offered the potential to side-step the ethical issues involved with organ donation and transplantation from living and dead donors.

“This technology has the capacity to alter the landscape of organ transplantation,” Professor Rogers said. “It won’t be possible to know whether engineered organs are better or worse than transplants from other (living or dead) humans for many years, so that we will stay in the "experimental” phase for a long time until long-term follow up trials have established safety and effectiveness profiles.

“This creates the possibility that there may be pressure for people who are refused conventional transplants to volunteer for or accept engineered organs. Second, if it seems that life with engineered organs is better - which it obviously has the potential to be, given that no immunosuppression will be necessary - then we may get a two-tier system in which those who can afford engineered organs will get them while others accept organs retrieved from humans.”

The results of this natural approach to tissue engineering were “quite dramatic”, said Martin Pera, the Program Head of Stem Cells Australia and Chair of Stem Cell Sciences at the University of Melbourne.

When creating the scaffold, however, “in order to avoid the use of animal products, and to get around the shortage of human donor tissue, it is likely that future research will focus on mimicking the natural templates with synthetic materials,” Professor Pera said.