The Azaria Chamberlain case is a reminder that the criminal justice system does get it wrong, with each error bearing its own human cost.

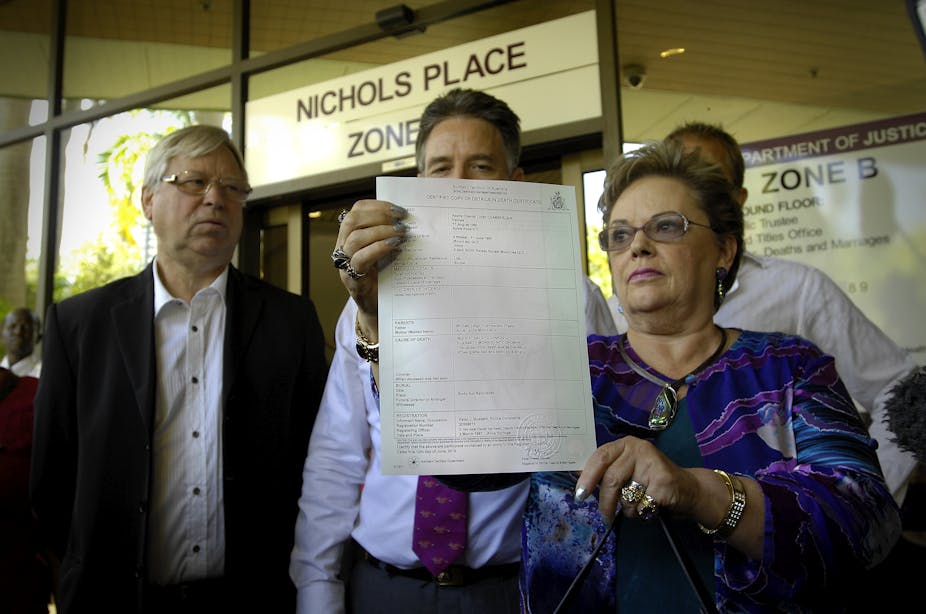

On Tuesday, the Northern Territory Coroner’s office concluded an inquest into the cause of death of baby Azaria Chamberlain near Uluru on the night of 17 August 1980. The finding: a dingo took the baby.

Despite the same determination in the original coronial inquest, Lindy Chamberlain-Creighton was tried and found guilty of the child’s murder in one of the most public criminal cases in Australian history. She was sentenced to life in prison and served nearly three years before new evidence and a Royal Commission Inquiry led to a pardon and reversal of her wrongful conviction.

The Chamberlain-Creighton conviction was based largely on the use of unreliable or improper forensic science during the trial. But the Chamberlain case is only one example of wrongful conviction following a flawed criminal trial. Many have been sent to jail or even executed on the basis of faulty evidence despite their innocence.

Innocence lost

The Innocence Project in the United States is dedicated to exonerating wrongfully convicted people through the use of modern DNA testing.

They report that in US history there have been 292 post-conviction DNA exonerations. From their experience, the seven most common causes of wrongful convictions are eyewitness misidentification, improper forensic science, false confessions, government misconduct, reliance on informants, and plain old bad lawyering – including defence counsel sleeping during trial.

Unreliable or improper forensic science was found to be present in 52% of the first 225 exoneration cases the Innocence Project have dealt with.

A lack of scientific standards for assessing the results of forensic testing methods was a key finding by Justice Morling in the Royal Commission Inquiry into the Chamberlain case. This unreliable evidence, along with unverified assumptions by experts, were presented as scientific evidence to the court.

Limited evidence

Despite advancements in forensic practice, modern concerns persist with respect to its use in criminal trials. For example, the term “the CSI effect” has been coined to describe the impact of television programs that depict a high level of sophistication in current forensic sciences. These shows foster unrealistic expectations among jurors as to the need for, and veracity of, forensic science in criminal trials.

Also with respect to jury trials, studies have shown that jurors can be prone to confusion as to legal directions and factual narratives, especially in cases involving complex evidence. They may also automatically defer to expert witnesses.

There is a large corpus of international human rights law directed at ensuring procedural fairness for defendants. These rights seek to balance the usually limited power of defendants relative to that of the state and to minimise the risks of injustice.

Key among these is Article 14 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) that ensures basic rights. These include the presumption of innocence, the right to silence, to be dealt with by an impartial tribunal, to be fully informed of charges and to participate fully in the examination of evidence.

Article 14 also confirms the right of all persons to appeal to a higher court and to compensation where new evidence leads to exoneration.

Deadly mistakes

But even with due process assurances, errors occur. In states retaining the death penalty such errors may result in the highest cost of all.

The Death Penalty Information Centre reports that in the United States 140 people have been released from death row since 1973 due to evidence of wrongful conviction. Some would say that this shows the criminal justice system working, as appeal processes have enabled the errors to be identified. To some extent this is true.

Sadly, however, there are cases where the error has not been uncovered in time or limitations in the system have worked against its recognition. For example, there is evidence to suggest that in 2004 Cameron Todd Willingham was wrongfully executed by the state of Texas. His murder convictions had been founded on discredited scientific theories as to how the fire that killed his children most likely occurred.

Earlier this year the Columbia Human Rights Law Review dedicated one of its editions to research detailing how Carlos DeLuna was executed in 1989 for a crime that he most likely did not commit.

Studies in the United States also suggest the race of a victim has a bearing on the likelihood of an imposition of the death penalty.

The death penalty and international law

International human rights law has yet to prohibit the use of capital punishment. Instead, Article 6 of the ICCPR limits its application to the most serious crimes and to defendants over 18 years of age.

Despite this, there is a global trend towards its abolition. This trend is supported by international instruments such as the 1989 Second Optional Protocol to the ICCPR which confirms that the abolition of the death penalty contributes to enhancement of human dignity and progressive development of human rights.

The Chamberlain case is a reminder that criminal justice systems are fallible. For the family in this case, the legal system has, as far as is possible, rectified the errors – the criminal conviction has been reversed, financial compensation awarded, and now the accurate recording of the cause of Azaria’s death.

Some wrongs can be rectified. But as philospher John Stuart Mill acknowledged in his eloquent defence of the death penalty in 1868, there is one argument against the practice which “never can be entirely got rid of. .. [T]hat if by an error of justice an innocent person is put to death, the mistake can never be corrected”.