On the first page of Long Island, an unnamed “Irishman” kicks Colm Tóibín’s new novel off in grand style by presenting a startling ultimatum to Eilis Lacey, the character at the centre of this love story.

Review: Long Island, Colm Tóibín – (Picador)

He announces on her doorstep that Eilis’ husband, Tony Fiorello, a plumber, has left his wife pregnant after a number of generous house calls to get her plumbing properly fixed. The Irishman states bluntly that he will be leaving the baby at Eilis’s front door in a few months’ time.

Even under the initial shock of this brutal Dickensian (or perhaps, more accurately, Swiftian) threat, Eilis manages to observe the man somewhat coldly.

He was, she thought, a man who liked the sound of his own voice. But she recognised something in him, a stubbornness, perhaps even a sincerity.

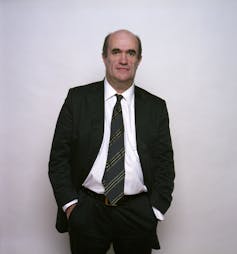

There is no doubt the prolific Colm Tóibín is an Irishman who likes the sound of his voice in writing and his many readers do too. It is a mesmeric voice. And what more do we need and want from our novelists than a beguiling voice and a mischievous stubbornness to get the story out, along with enough of what we recognise as sincerity?

The Irishman at the start of Long Island disappears as quickly as he appeared. We are left with this vivid reminder of what kind of man might be behind this smoothly told tale of love misdirected, misunderstood and misjudged.

Perhaps it is a dangerous thing for a novelist to write a sequel, for it limits the readership to those who have read and remembered the earlier work and a lesser number who have admired it enough to want to follow this new development. In this case the prequel is Brooklyn, a novel published 15 years ago. But equally, it is naïve to assume writers plan their works in wholly deliberate or strategic ways.

Ideas take hold, characters make demands, talent bends in certain directions, the slant of light in a room on a certain day can suggest a whole world demanding to be written. In any case, these two novels work wonderfully well side by side and could be equally engaging if read as single works. There is enough back story in Long Island to allow it to stand alone, though as a reader I am grateful for the pleasures of both novels.

An explosive

Where Brooklyn was a book of suspended decisions and relentlessly increasing pressure, Long Island lets off its explosive at the very beginning for us to then watch, over the next several hundred pages, the aftermath.

In Brooklyn, what is solid about the world comes too quickly to seem to be a dream, and what begins as dream becomes solid. Each character finds they must choose a life to live while time and events won’t pause long enough for them to delay too long over making that decision.

In Long Island, a decade and a half later, there is less dreaming, decisions are finally made. But the characters find each decision has only opened them to the necessity of making further and more decisive commitments to the life they will have to live and the person they turn out to be.

These characters hold desperately to the notion they can and do make decisions, that free will does exist. Eilis holds her husband to account for his decision to be unfaithful when she declares she will not ever tolerate even glimpsing this illegitimate baby on its way to her doorstep.

But in a very Catholic move, we are asked, eventually, to contrast Tony’s blatant insult to a marriage with Eilis’s slower burning, more subtle and persistent infidelity of the heart.

Who has been most wronged in this marriage? Is there after all something healthy in Tony’s reckless action and his family’s pragmatic reaction, in contrast to the paralysis, ethical failures and foolishness that come from being chronically unable to be honest with oneself? The novel throws such questions at our feet.

Both books are about silence. That kind of silence produced in a noisy family constructed out of secrets (Tony Fiorello’s tight-knit, intergenerational, American-Italian family) and another kind of silence produced in a small town where everyone knows everyone else’s business but won’t bring anything the least embarrassing or unconventional out into the light.

And there is the more intimate silence of characters who cannot speak their mind for fear of closing down options in their lives. When Eilis says she never wants to see the coming illegitimate baby, she cannot, for instance, speak out loud the “or else” contained in that statement:

She wished she could speak clearly to Tony as he drove, let him know once and for all what the consequences would be if he and his mother did not see sense. But if she spoke, she would lose him. He had already decided what he would do about the baby. Once more, she saw that if she made threats, she would mean them. And it was that knowledge that was stopping her from speaking. She was not sure she wanted to lose him […]

The tragedy of smallness

Words can expose us to the realities of power in a relationship, and words can make things clear, sure, but irrevocable. While the characters choke on their silences, or grow smug on them, Tóibín lets us into all the swirling secrets, which is both a lot of fun and a source of exquisite discomfort.

Tóibín’s considerable skill is in bringing us into close sympathy with these characters so instead of a comedy of manners we have the tragedy of smallness. Jim Farrell, the publican in Enniscorthy across both novels, is a man we can’t help but warm to as he falls in love with Eilis, is forced to accept her apparent decision to leave Ireland, then makes of his life a calm and harmless bachelor businessman’s routine that offers the town a pub worth going to.

That he then falls headlong into the ruses, silences, suspended decisions and lies of omission like almost everyone else in Long Island becomes a cause for our distress as readers. We want to shake him by the shoulders until he acknowledges there might be some right way to go in his small, singular life. Tóibín’s Jim Farrell becomes a powerfully felt portrait of a limited man caught in the headlights of twin possibilities.

Both novels develop portraits of men and women, and the men and women seem very different creatures. Mostly the men are dim, mild, easily distracted by sports, keen to get to a nearby pub, dazed by ethics, eager to be loved but careless of the women that love them. Even when they’re good it’s in a gormless way. I can’t help but think these two novels are not much interested in the men, for they more or less deserve what they get.

And what they get is more or less what the women decide they will get. Tony receives his ultimatum and Jim does too eventually. The women on the other hand, and in particular the lovely Eilis, put in an effort to do the work of feeling, sympathy, management and the truly hard work involved in loving.

Tóibín’s female ventriloquism, if it could be called that, takes an extreme turn in Brooklyn with Eilis’s early experiences of sex with Tony, her husband-to-be. Tóibín writes of her second time with Tony as if describing a form of reckless rape:

This time the pain was even worse than before as though he were hitting against something inside her that was bruised or cut.

“Is that better?” he asked.

She tightened as much as she could.

“Hey, that’s beautiful,” he said. “Can you do that more?”

The moment is shocking for its explicitness in the context of the novel, and also because the narrative simply moves on from this as though Eilis, as much as Tony, has no other expectation of love. Brooklyn is set in the mid-20th century, leading into the more experimental years of the 1960s by the time of Long Island.

And though there are trysts in hotel rooms and a long secret affair in Long Island, that novel doesn’t go into details of love-making, perhaps because the characters are older now and might either know what they are doing, or have shaped their expectations towards other, more lasting, questions about love.

Finally, these novels, and Long Island in particular, offer us a portrait of the town of Enniscorthy on the east coast of Ireland in County Wexford. It is Tóibín’s childhood town, and the streets are described with easeful accuracy. The pub perhaps is modelled on the hotel he worked in as a barman at 17.

At the centre of the town is the character of Eilis’s mother, a woman of irony, wit, reduced horizons, labyrinthine cunning, and an almost magical absorption of gossip which could somehow reach her in the semi-dark insides of her home. She almost steals Long Island.