Australia is not doing well in the international literacy and numeracy attainment rankings and many rightly point out the funding issues, clearly identified in the Gonski Review, as central contributing factors.

Funding is a critical issue and the complexity of our schooling system funding does set us apart in international studies of schooling. However, if, as a parent or student, you’ve hmmphed at the news media and thought it’s not what you spend but how you spend it, you are also right.

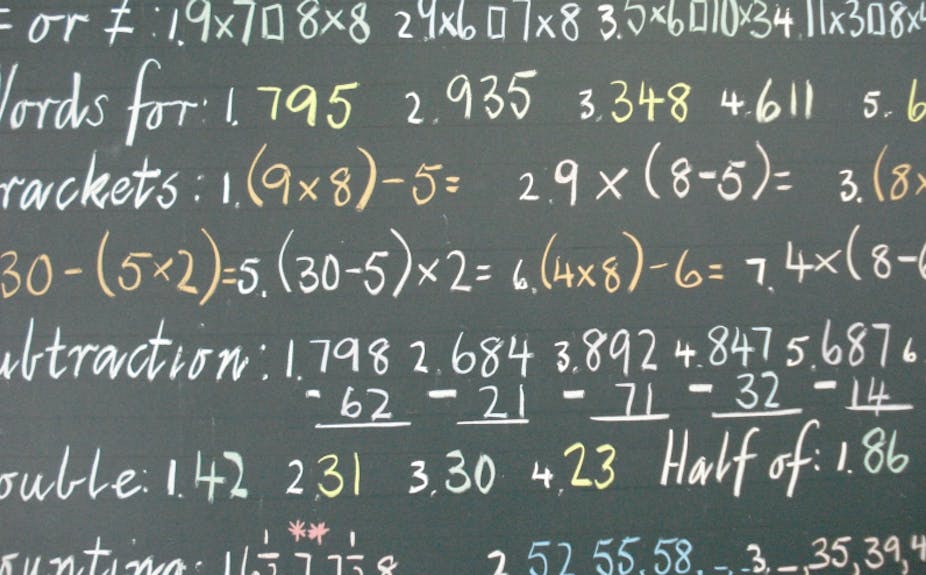

Here’s one simple example of what can be done.

Make maths mandatory. Australia is quite possibly the only developed nation on the planet that does not mandate maths study for high-school graduation. Surprising?

For most education systems a maths requirement is assumed. Yes, in the UK is it not a requirement for A-levels but it is required for the equivalent of Australia’s year 11 at GCSE. Across the USA and China it is a requirement for high school graduation, as it is in high attaining countries like Finland, South Korea and Singapore.

Maths should not be optional

Many young Australians will not have studied maths to year 12 level. It is not a requirement in New South Wales, Victoria and Western Australia; although it is compulsory in SA, and to a small extent in Queensland and the Northern Territory. In New South Wales the requirement for HSC maths or science study was removed in 2001; since then there has been a dramatic drop in maths with one quarter of students completing the HSC without maths. Many of these students have gone on to university and to teaching careers.

While there is a requirement for New South Wales primary teachers to complete general maths, many early childhood and secondary teachers are maths-free - yet expected to teach numeracy. Early childhood centres with an emphasis on the development of maths, through play, show better child outcomes overall. But many future teachers will disengage from the subject and because of a maths phobia that prevents them from using maths in their teaching. Thus some of the new generation of teachers may unwittingly set up a viscous circle of diminishing numeracy skills within our society.

The National Numeracy Review reported dramatic drops in national participation in maths since 1995 but the issue is yet to be addressed. As a nation, how can we value numeracy, and worry over international performance, if we are sending messages to students and teachers that maths is an optional element of education?

In this information age, deterioration in numeracy will pervade education, producing teachers who find it difficult to engage with technology and with educational data. By contrast, highly numerate countries, such as South Korea, are making rapid advances in education across curriculum areas because teachers have high levels of numeracy and scientific skills with which to organise, analyse and improve their teaching.

I am not saying that all teachers need to know calculus. Rather, they should be confident in the maths curriculum of the levels that they teach and comfortable in dealing with quantitative assessment data. In one study only one third of primary education students could attain 90% or above on Year 7 numeracy tests without further instruction.

The role of NAPLAN

Strengthening teachers’ numeracy skills is also needed to fully harness the shift to Assessment for Learning. The evidence is in: assessment, and they way teachers and students get to know each other through it, is powerful. However many teachers are seriously challenged by assessment because it requires them to be comfortable with data and numbers.

NAPLAN’s potential has been hampered by poor timing as teachers are not able to access feedback until late in the year which seriously hampers the way it can inform their teaching. However advances in technology, as seen in New Zealand’s ASSTLE system, can address these issues. What is more critical is that teachers are suitably skilled in maths, IT and data use so that they can harness the potential to improve their performance and drive student learning.

Academics in teacher training who oppose NAPLAN claim it is being used to assess rather than develop learning, however it is the job of teacher training to ensure that teachers are skilled to use NAPLAN to drive learning. With assessment it’s not what you do, but how you do it. Education academics are responsible for developing skills and sophistication in teachers that ensure we encourage learning and minimise harm from assessment. Technology now provides us with the tools to do this but, again, a lack of scientific engagement among some faculties limits their capacity to do so.

Time for change

It is true that Australia’s recent performance was weakest in literacy; however among the many factors contributing to the poor performance the decline in maths participation is influential – and one which could be remedied.

It’s time to make maths mandatory for high school certificates, make maths mandatory for all teachers and build a numerate culture in teacher training.