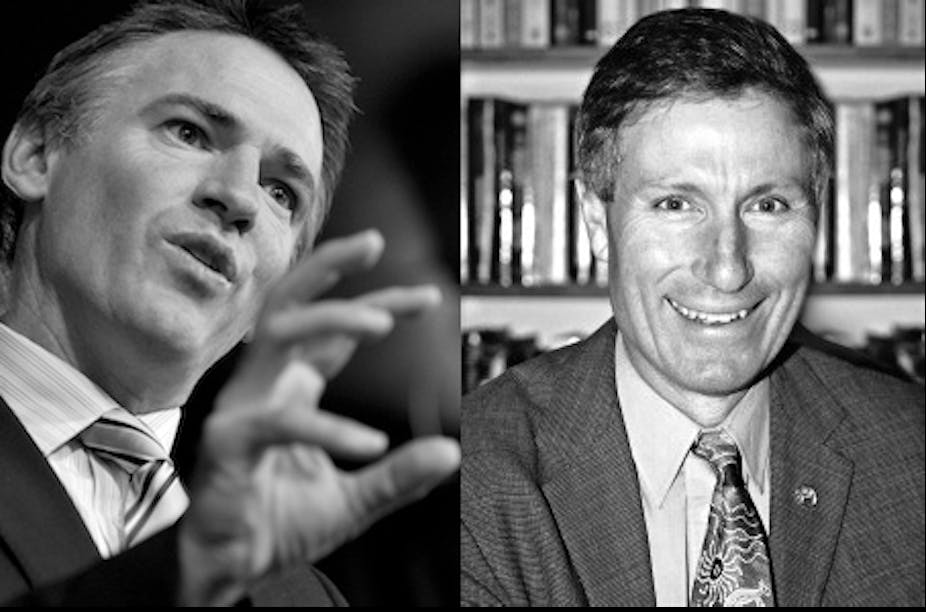

For the latest in our In Conversation series, Adjunct Professor of Political Science at the Australian National University, John Warhurst spoke with the Independent member for the NSW seat of Lyne, Rob Oakeshott, about the state of Australian democracy.

The 2010 election resulted in a hung parliament, where neither the Australian Labor Party (ALP) or the Liberal/National Coalition challengers won a majority of seats allowing them to govern in their own right.

It was this hung parliament - the first at Federal level since 1940 - that saw a number of independent and minority party MPs assume the role of kingmakers.

Despite having won a traditionally conservative seat from the National Party, Oakeshott decided to support the minority ALP government lead by Prime Minister Julia Gillard. He made the decision after negotiating a package of concessions which included significant parliamentary and political reforms.

Key points in the discussion include:

The progress of the democratic reforms he sought as his price of support

What it means to be an independent MP in contemporary Australian politics

Political parties and their relationship with vested interests

How the media relates to politics

Indigenous Australians and democracy

Constitutional reform and the possibility of a republic

Warhurst: I went back to your first speech…

Oakeshott: Still awake?

Warhurst: It was great stuff. You were a new independent member of parliament, and that’s where I wanted to start. Independents have quite a brand in Australian politics, partly because of your role both in federal and state politics. In that speech you were talking about a new era of representation. Could you just talk about what it means to be an independent and your contribution to Australian democracy?

Oakeshott: It’s nothing new, it’s really trying to invest in parliamentary processes and the original concept of what a parliament is. I was a member of a political party, I’m quite open about that, but I found it difficult to run on to the footy field with two jerseys on – one being a political party, one being community.

Warhurst: With the party jersey firmly on top, I should think.

Oakeshott: Well, that’s right and I took that one off and I didn’t know how it would go. But for me personally, I sleep a lot better at night as a consequence. There is no moral wrestle going on, you do make judgments based on their merits, based on the legislation before you and then you are a part of a parliamentary majority or minority, wherever those cards might fall.

For me, being an independent is the investment in the original concept [of parliamentary democracy], that is it simplifies the whole process. But it also lifts the process in my view to one where critical thinking has status.

Warhurst: You talked about place-based thinking in your first speech, can you explain that concept a little bit?

Oakeshott: That really is a bit of a counter push to political party thinking, place-based thinking is very much about trying to empower local communities. So it’s taking the model of an independent member and getting elected by 90,000 people and their lovely support and then weighing up issues on their merits.

It’s actually also investing in, at a local community level, in health or education whatever it may be, empowering people to take control of the issues and provide suggestions and provide direction.

My job then becomes a lot simpler, in chasing and advocating for money or types of programs that very much fit in with ones that are on the ground. So it’s really just value-adding rather than necessarily re-inventing wheels on the ground.

Warhurst: So you see yourself as an intermediary? So rather than being out in front, you’re going back to the community and saying “what do you want”?

Oakeshott: When it comes to program delivery, yes. There are times that you do have to lead, times you very much follow. But when it comes to program delivery, I think a big failure of public policy in Australia, and everywhere, is when there isn’t that investment in how, in a practical sense, programs are going to be delivered on the ground.

And unless you’ve got early stakeholder engagement, and this comes out in a lot of research work, that unless you’ve got a good strong relationship network on the ground, programs are going to struggle.

And therefore, from a local member’s point of view, regardless of independent or not, I think a big investment of time and energy is in making sure relationships on the ground are as strong as possible. So when programs do come down the line, we’re ready to go.

Warhurst: And what about vested interests, have they pulled back a bit? In your speech, you also talked about vested interests often going ahead of the community interests in the way politics is played in Australia?

Oakeshott: This is a personal view, I think … what is a political party today? It’s a vehicle for vested interests to control agendas. That’s why so much noise in the [current hung parliament], so much noise is coming from those traditional vested interests. Because it is normally very easy for them to talk to the Treasury benches when it’s a majority government, one way or the other.

You can talk to half a dozen people and hopefully have some clear direction and some certainty, but also some confidence that you’ll get what you want.

Warhurst: Do you think the political parties are beyond redemption? Or can you see any sense in which perhaps over the last three or four years, they’re learning some lessons?

Oakeshott: This hung parliament is really interesting in that amongst parliamentary colleagues and also amongst the community, we’re going through a whole process of trying to work out what it’s like to have a parliament with a heartbeat, for good and for bad.

And I don’t think we’re across the line there of really understanding the powers of what we’ve got – both at a parliamentary colleague level and a community level.

I think we’re still going through thinking, “this thing’s frightening,” for honest thought and honest ideas. And so at the moment the Woolies or Coles, the Ford or Holden mentality in Australia which is our tradition of Labor or Liberal…

Warhurst: Not much choice there for the average citizen.

Oakeshott: But I think it’s winning the day. I actually think there is a level of comfort still in majority government because in my view, you don’t have to think as much.

The vested interests do all the work behind the scenes with the political parties, caucus room or coalition party room – that’s where anything happens and it’s clean.

Whereas from my perspective, better policy comes from accountability and transparency on the floor of the parliament, no one controls the agenda, everyone shares a bit of the risk and that is a much better outcome for public policy even if it is a little bit more uncertain.

Warhurst: And a bit messier?

Oakeshott: Oh, it is messier because you’re getting to see the fights, politics is about the fight, it’s not behind closed doors, it’s on the floor of the parliament.

So I would hope at the end of this three years, in answer to your question, the political parties get some of the advantages of parliaments with a heartbeat, parliaments that are alive and try and incorporate that into their business models.

For example, Malcolm Turnbull is in the room next door, so giving some people who have good ideas freedom to express them on the floor of the parliament rather than playing this traditional game of so-called party discipline which is, in my view, almost treasonous. You are denying someone the opportunity to express their views on behalf of their constituents.

Warhurst: So do you think one of the impacts you are having is that other MPs, Labor or Liberal or National, are looking at you and saying, “Gee, I could do with a bit of an injection of independence”?

Oakeshott: Without a doubt, the main reason members, particularly backbench members, really put some heat on independent MPs, in my view, is that they can see what they don’t have and that is the freedom to express views on behalf of their constituents and freedoms to make decisions on the floor of the parliament based on their merits.

That is the original concept of a parliament, we’re not bringing anything new to the table, we’re not re-inventing anything. But that has been given up by those who have chosen the path of the political party and in one sense, it’s an easier path with all the money of campaigning – it’s much easier.

But from my perspective, it is also a lot harder once you are elected because you really do give up a lot when it comes to moral conscience and representation. And that’s why it comes down to – “how dare you have an idea, how dare you express it!”

Warhurst: So in general terms, how do you think the first year of a minority government has gone?

Oakeshott: Process-wise I think it’s been good. Legislation is passing and that is the bottom line test and not easy legislation, some of it is hard.

Warhurst: Better legislation do you think?

Oakeshott: Well, I think so because there is more accountability and transparency, and all of us who are on either the cross-benches in the lower or the upper houses have saved governments throughout various points in the last 12 months from putting themselves into stupid positions.

As we have worked with the Coalition at times, from the opposition benches, so that is the way a parliament should work, all ideas welcome. It goes through a process of compromise, negotiation, and oversight and transparency and through that you get the best policy you can.

So I think from that perspective, it’s working.

The politics is ugly, and that goes back to that previous point, I think everyone is still working out just what is this beast that we’ve all created. And in the end, from my perspective it’s pretty simple – it’s the original idea of what a parliament is. All ideas are welcome, participate in the process and we will be stronger as a consequence.

But there are those that are wanting to say majority is better because there is less to fear. I think some of that politics is cutting through because it doesn’t require as much thought and energy to participate.

Warhurst: And that has led to some communities to call for an election to have a majority government.

Oakeshott: Well, calls for citizen-initiated referenda is the model which is, if we really get down to it…

Warhurst: Yeah, happy enough with that, sure.

Oakeshott: It is based on issues of contention which have been around, it’s based on a price on carbon, people feeling they’ve had three goes at the ballot box already and wanting a fourth because they view that as the opportunity of the moment, where there’s only one vote difference between government and opposition.

I would be surprised if the same politics was being played if there was a clear majority government. And the other thing is, if we’re talking pricing carbon and early elections, there is an important bit of democracy that is being missed and that is, one of the up-sides of this parliamentary reform and private members bills, and some have been successful in the first 12 months, there’s an opportunity for any member to put up a bill on anything including a direct action policy.

So for those that are leading the call for early elections under the guise of democracy, well, true democracy would be that you’ve got an opportunity to get your legislation through at the moment, why do we have to wait two years.

Warhurst: You mentioned private members’ bills, is that one aspect of your agreement for parliamentary reform that you are happiest with or see as most important? Or would there be other key reforms you would point to?

Oakeshott: The private members’ bills I think is the one. It opens up from just being a show about ministers and the executive to 150 members of parliament in the lower house matter, and do have the opportunity to participate. So everyone needs to be thinking, it’s not all care, no responsibility from opposition. If they’re going to put something up, it will get tested and it could get up. And I think there’s been three or four that have got through in the first 12 months.

The committee structure is generally the other area, I think most members are happy that there’s a bit of a re-investment in the committee structure of the parliament. So there’s a process now for referral of legislation to committees, ministers have to respond within a certain timetable, if there are going to be amendments that’s the opportunity for that to get flushed out.

So when legislation in its final form goes through, it’s been thoroughly tested and in a pretty efficient way. It’s not slowing the show down too much.

Warhurst: Is the question of an independent speaker still a live one for you?

Oakeshott: It is a live one, I wish the speaker, [Harry Jenkins] would use more of the authority that he has been given. And I think it’s still early days, and we are still working out what we have created.

I still get people saying Question Time is terrible, how can you say there’s been parliamentary reform? Well, an independent speaker now has the authority, without points of order, to pull people up on relevance on questions or answers.

And I continually urge him, and her in the future, to do that. They have unlimited powers to make sure the place runs smoothly.

Warhurst: Sounds like with parliamentary reform as a work in progress that a full three-year term is really essential for the lessons to be learned and the processes to be embedded and for cultural change to come about.

Oakeshott: Specifically for parliamentary reform, yes, the longer the better because it is a cultural shift. The nervousness will be when majority governments do come back, if and when, in the 44th parliament, how much will be retained and that’s where the cultural change..

Warhurst: I suppose the odds are some time you will get a majority government, if not next time, the odds are it will happen.

Oakeshott: And that’s where, as much of it is culturally ingrained will survive. And that’s why it’s been so important to engage the major political parties and make sure they’re comfortable. And on the vast majority of it, they are.

There’s some issues around the sitting timetable, there’s been some mini-revolutions on but most stuff people are pretty happy.

Warhurst: Speaking of cultural change, you said earlier on the idea of independent MPs was catching on around your whole district, in terms of local government and state government, then a setback or two. And I was just wondering, what you thought…

Oakeshott: You just met [Peter Besseling].

Warhurst: Oh right, he was the state MP for Lyne, now the penny drops. I saw him play for the Brumbies years ago. But without being too down about all that change, does it mean that the cultural change was washed away?

Oakeshott: Others before me or alongside me are more sensitive about independents versus political parties, I’m not. I’m more about independent thought, so critical thinking and that’s where, if I can be part of a process that lets a few political party members off their lead a bit… I’m more about a parliament being alive and having a really important place alongside, and ideally above, an executive rather than just being dead.

In fifteen years of public life prior to this parliament, the number of times I have sat alongside people who didn’t have a clue what they were voting on – and it’s disgraceful and it’s not representation. And if they’re disengaged, community is going to be disengaged and it’s policy by apathy.

Warhurst: If one outcome of your role was a revitalised political party system and better candidates and more direct elections…

Oakeshott: This whole idea of party discipline is one that really grates me. And Australian political parties are some of the worst anywhere in the world, Republicans and Democrats work together in the US, the whipping system in the UK, you get the freedoms of one, two or three ticks next to legislation. Even some of that would be a breakthrough for Australian public policy.

Yet there seems to be this cultural mantra that you only win elections if you speak with one voice, and that might be true, so maybe the audience of Australia needs to be more comfortable with a range of voices coming from either a political party, or a parliament.

And hopefully, what this parliament can contribute is to some of that, is to make people comfortable with more than just Ford and Holden, more than just Woolies and Coles. There’s a lot of grey in most ideas and the joy is exploring it from a whole lot of different angles and you get better policy as a consequence.

Warhurst: A lot depends, of course, on how the media report what’s going on in this building. Are the media one of the vested interests that need to learn what this new era is all about, the new ways of doing things?

Oakeshott: I think they know, I think media know.

Warhurst: They know? Alright. Well, are they playing the game?

Oakeshott: I think they are, I think part of it is still adversarial, it still is through implications to prime ministers or opposition leaders and in many ways reading more into policy suggestions than probably what is there.

How about policy for good policy reasons rather than good political reasons? That doesn’t get much air time.

But one of the reasons I’m a supporter of a media inquiry is I do think there has been some blurring of the lines between media, business, political interests, old media, new media – just what is media today?

I think that’s a good question. Is this [interview for The Conversation] media? Therefore, does it fall under the Press Council or the Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA) or you know, what is this that we’re doing now?

So I think there’s some fertile territory not to change a topic or not to be part of a socialist, communist takeover of free thinking.

It’s actually in defence of good journalism and in defence of free thought that we make sure truth has its place on the landscape.

I think there are some good brains in the media that know exactly what’s going on, it’s whether that suits various agendas within the media, whether that is reported, whether the truth of the moment [is reported]. Whether the power sharing is welcomed or not.

For example, I’ve had plenty of journalists say, “this is really hard to report.” That’s a good thing, not a bad thing! It used to be easy, you’d ring a minister and get a story. But the fact that they don’t know 100% to give that story, I think is healthy - a positive not a negative.

Warhurst: One of my gripes is that the way politics is conducted is encouraged by the media, that is the adversarial nature of it and the nastiness which I think contributes to turn-off by average citizens.

Some get turned on and want to march on parliament. But I think a much larger number of people just say, “to hell with it, that’s not the way we think, people should speak to one another, argue cases and all these sorts of things”. And I think some of the media plays into that.

Oakeshott: Very much so, and in my view the last decent media inquiry was the 1991 print media inquiry, and that’s when the internet really came into vogue.

Warhurst: A lot has changed since then.

Oakeshott: In the last five years, anonymous blogging has really changed the discourse in my view and newspapers have struggled with the question of how does this sit alongside what they do?

But what I’m noticing a lot of them do is have this anonymous blog page, which is just a free-for-all, it’s just a character assassination because it’s all anonymous. But then that drags the general tone of discourse down, it becomes all about character assassination, that’s the game. So you know, you used to have to put your name to what you’ve said.

Warhurst: And it is toxic, to use the favourite word of one of our political leaders. I think it’s a real turn-off and it’s unaccountable.

Oakeshott: I actually think in the last month, it’s starting to twist and that’s why I mentioned those community forums before, I just did six of them last week and I noticed a lot more people are starting to push back. [With] talk back radio, they’re being a lot more critical in their thinking about what are we listening to and are we being told fact from opinion?

Warhurst: And do these forums get conducted in a reasonable way?

Oakeshott: The first 15 minutes is a free-for-all, you know, they say “you’re a bastard for pricing carbon or for going with Julia Gillard.” And then once the lid had been blown on that, at most meetings there was about 30 questions on a whole range of different topics and a lot of interest and a lot of engagement back and forth. So that’s the way it should be.

Warhurst: Could I go back to your first speech again, you talked quite a little bit about [laughs]. I’ll re-phrase that.

Oakeshott: 17 minutes.

Warhurst: You said that, not me.

Warhurst: At the beginning of your first speech, you were talking about indigenous Australians and it strikes me, in terms of policy outcomes, if you’re going to measure the success or failure of a democracy then how indigenous Australians have been treated, what their situation is, is one fair measure of whether we’re fair dinkum about fairness, equity. Do agree with that?

Oakeshott: I think that’s our benchmark, very much so.

Warhurst: Would you like to do specific things in that regard?

Oakeshott: It’s a combination of what we’re talking about before with place-based thinking. Community empowerment is the missing link.

Warhurst: Empowering the people who really don’t have power, isn’t it? Not just everyone in your local community because some of them will have a little bit of power, it’s the others.

Oakeshott: Yes, and that’s capacity building, that’s the place-based model and there was only last week, Channel Seven got that cabinet-in-confidence document of all indigenous expenditure programs showing really questionable outcomes for big dollars.

And I don’t think that’s a blight on those trying, nor is it a blight on those who at a community level are wanting to get better health, or education, or employment outcomes. It is just this complete disconnect between the two.

And so that is, in my view, a very big role that local members of parliament do and should play is that place-based thinking and really engaging and helping connect Canberra with community. And indigenous health, education and employment programs are some of the most challenging but when successul the most rewarding.

And they are the benchmark, if we cannot address the plight of indigenous Australia as part of the Australian story of today – we’ve failed.

Warhurst: You’re planning more forums, I presume it’s part of your whole process, rolling forums. And do you find that people understand your job here in Canberra?

Oakeshott: Increasingly, but no. I think that’s part of the explosion of the moment of a tight parliament is the fact that civics isn’t good in Australia.

Warhurst: Even when it’s there, it tends to be a bit dry I think.

Oakeshott: I think we’re about half way there but there is a fundamental misunderstanding of many aspects of what it means to vote for someone.

Whilst lots of the language is that you are a servant of the people, that doesn’t mean you are a slave. It doesn’t meant that you agree on 100% of someone’s issues or items because there’s 90,000 [opinions].

Warhurst: Yes, you can’t agree with everyone.

Oakeshott: I think there is a real grappling with that at the moment, and maybe it’s because I’m at the pointy end of the numbers, but I’m enjoying really talking it through with my communities, and just watching people grapple with what representative democracy does or doesn’t mean.

Warhurst: So with two years to go in this term of parliament, what are your priorities in terms of putting into place what you envisaged 12 months ago, both in terms of what your vision was for Australian democracy as a whole and parliamentary reform in this building?

Oakeshott: So the one thing that particularly Tony Windsor and I talked about a lot, in fact we were criticised for talking about it so much, was stability.

So we didn’t talk about “good government” necessarily, we talked about a “stable government”.

And I think that is a foundation that is the least we can provide for as long as possible, these were unique cards that were thrown up by 22 million people and so if we can, at least keep it running as long as possible, I think that is some good work.

There’s a whole list of outcomes, local and national, there’s about 85 parts of my agreement over supply and confidence. Most are now ticking along.

The next big one on the radar for me is the National Tax Forum in early October and really having a wrestle with the Treasurer about many aspects of that. I think we all get the sense that they’re trying to play it down and I’m trying to play it up.

Warhurst: Maybe the executive doesn’t quite understand the new era?

Oakeshott: Yes, so that one is on for young and old, and hopefully we can get some really good fairer and simpler tax outcomes as a consequence on the back of, what I consider, the very good work of the [Ken Henry review].

I think this session of parliament there’s going to be about half a dozen items, there’ll be education funding which is a really interesting one.

The Gonski review will land before Christmas but so far so good from all sectors, there seems to be a bit of faith in the process. So he’s done a fantastic job up until now in what is a hotly contested area.

The private health issue is going to be on in the next couple of months, the 30 per cent rebate, the Minerals Resource Rent Tax and all the implications of that. There is a lot of interest locally and nationally around gaming reform, so that one is hot to trot.

Warhurst: And of course, one of your fellow independents, Andrew Wilkie says he will bring down the government over that issue.

Oakeshott: And so that’s an interesting one awaiting legislation, and that’s just off the top of the head. And that’s not talking about the local ones, either connected to that or separate all together.

Warhurst: So it’s not going to get any easier.

Oakeshott: No, it won’t get any easier. Constitutional reform in regards to indigenous recognition is one that I’m involved with and again that will probably have some public statements prior to Christmas.

In regards to next year, that one will become increasingly important. The National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) – making sure they actually stump up and go through with that I think is really important.

Warhurst: Same sex marriage and other social issues?

Oakeshott: That one will more than likely get a run in the next three to six months. And the only one that I really think in all of that, that we haven’t touched in a tight parliament, there will be two constitutional questions, so there’s local government which I’m wanting to be convinced on and the indigenous one, and then the one which I hope everyone agrees is a no-brainer is the head of state question.

Warhurst: It would be fantastic to do something there, Rob.

Oakeshott: Well, that’s the only ball that is not rolling in some form.

Warhurst: Well, I would love to push that ball along and if you were happy to push it along that would be fantastic.

Oakeshott: It’s picking the right moment because I think the dance card between now and Christmas is very full. But how we look next year depending on whether the economy is still strong, the fundamentals around the economic issues is strong, that will be an interesting ball to roll and just see where Australia stands in 2012.

Warhurst: Thank you very much, Rob.

This is a transcript of the interview which has been slightly edited for fluency and concision. See the full interview here.