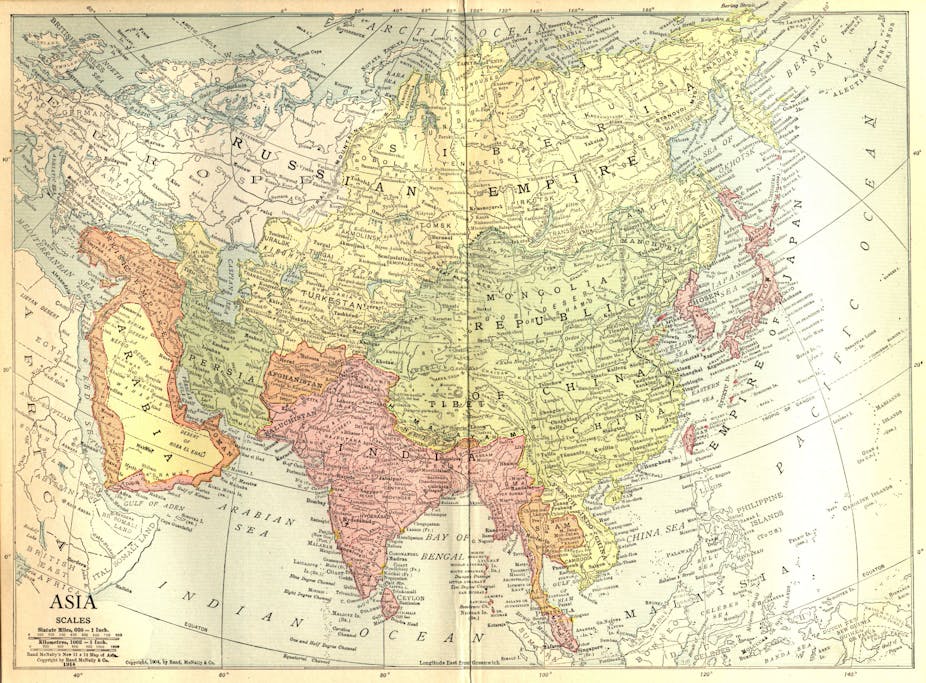

It seems 2012 was all about Asia: from the Australia in the Asian Century White Paper, to the possible repercussions of the Obama administration’s “Pacific turn”, and the continued rise of China. These conversations will continue into next year’s federal election.

While the specific shape of recent discussions of Australia’s place in the world may be new, the underlying dynamics that frame the debate are not.

They are informed by an enduring sense of isolation and ambivalence in a nation torn between its traditional Western allegiances and the promise of economic prosperity signalled by China becoming its largest trading partner. This tension between history and geography has long characterised the language of Australia’s political leaders.

Stories of Asia

Over 110 years of election contests in Australia, campaigning leaders have sought to construct a compelling narrative of Australia’s place in the region and the world. They have engaged in contests over national identity and security, inviting voters to worry about potential cultural, economic and even military threats from Asia and the Pacific and then reassuring them that, if elected, they would manage these threats.

These stories lie at the heart of election campaign communication. When political leaders appeal to the nation for their votes, they speak to ideas about the community: who we are and who we want to be.

In research published in this month’s edition of the Australian Journal of Politics and History, I traced national anxiety about Asia and the Pacific region in Australian election campaign language since Federation.

I analysed almost 1000 pieces of campaign communication, from radio and television interviews to press conferences and policy speeches. This analysis reveals the evolution of the specific language through which we collectively “worry” about, and manage, perceived regional threats.

Civilisation and liberation

In the first decades following federation, political leaders such as Alfred Deakin and Joseph Cook spoke of the role Australia (as a member of the British Empire) could play a role in spreading “civilised” values to an “uncivilised” region. By bringing “peace and order” to surrounding nations, as Deakin put it in a 1903 policy speech, Australia could ensure that the unknown region would become familiar and British-Australian identity would be secure.

After World War II, a new image emerged, with leaders painting Australia as a benevolent force that could help counter regional instability. In the 1966 election, for example, both Arthur Calwell and Harold Holt characterised Australia’s interventions in the region as helping manage processes of change. For Calwell, Australia would assist with Papua New Guinea’s moves towards independence; while Holt saw the nation’s role in Vietnam as helping stop the spread of Communism. Australia’s involvement would help to make the neighbourhood calmer and more stable.

Engaging the neighbours

From the 1980s onwards, frameworks of engagement and opportunity have characterised contested campaign debates over Australia’s national values and priorities. The campaigns of the 1990s, in particular, featured passionate battles over the future of Australian identity.

In 1993 and 1996 Paul Keating, drawing on the legacy of his predecessors Whitlam and Hawke, talked of Australia as naturally belonging in the region. His opponents contested his vision by emphasising traditional images of Australia’s identity and security.

In 1996, John Howard successfully argued against Keating’s picture of an Australia that would find its true identity in engagement with Asia and the Pacific. He contrasted the Keating regional vision with his offer to support families, protect job security, and ensure that “traditional” identity would not be challenged.

The need for control

Despite this evolving language, a constant refrain echoes throughout Australian campaign history. While constructing the perceived “threat” in different ways, campaigning leaders have consistently attempted to reassure voters that they and their party could manage these threats. A vote for us, they argue, will help Australia take advantage of opportunities, protect against threats, and therefore safeguard national identity.

This language, at its heart, is about reassuring Australians that they are in control of their own identity as well as their borders and prosperity. Leaders from both sides of politics promised Australians that they would protect not only their communities and values, but also the national space in which they flourished.

21st century angst

In the campaigns of the 21st century, this manifests most clearly as a desire not to be left behind by the rapidly developing economies of neighbouring countries. Kevin Rudd’s 2007 campaign rhetoric exemplified this, when he spoke about Australia falling behind its neighbours in education and broadband development.

Rudd’s anxiety about Australia’s ability to compete in the region betrayed a deeper fear of the recasting of the balance of power in Asia and the Pacific. In the wake of a rising China and strengthening economies in places such as Singapore, Japan and South Korea, his campaign language searched for a new image of Australian identity that would enable voters to feel secure in a new kind of region.

The lack of focus on national identity and security in the 2010 election campaign was unusual by historical standards.

But there are signs that next year’s federal election will feature a more robust debate about Australia’s relationship with Asia and the Pacific.

This will continue the public struggle that has unfolded across more than a century of election campaigns over Australia’s anxiety about its place in the Asia Pacific region, and its quest for a secure identity.