Stock market trading has been transformed over the last two decades in ways that are fated to increase the likelihood of complete market collapse.

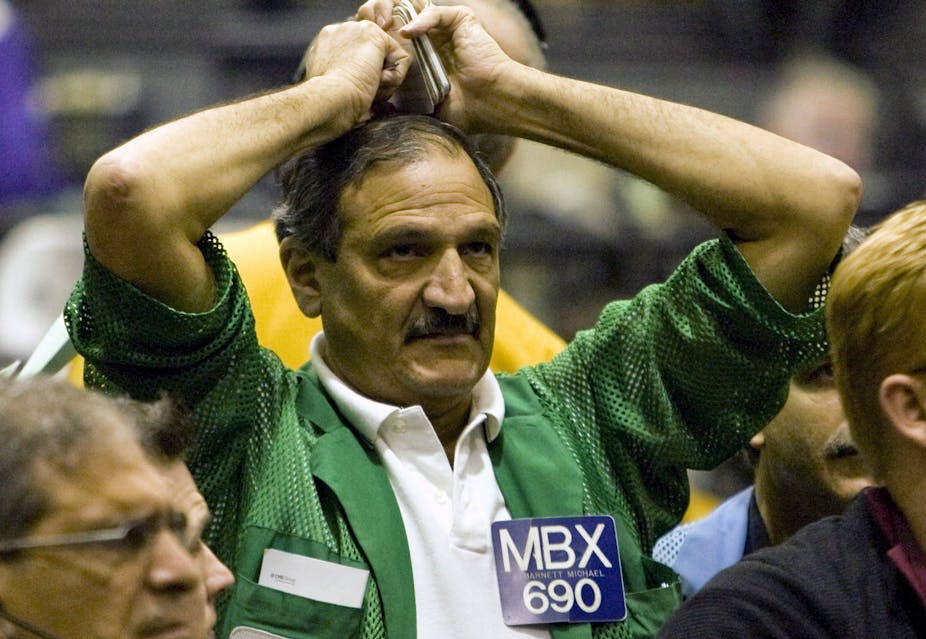

Stocks used to be traded by human beings through shouted buy and sell bids (the “open outcry” market).

Trades could only be made when the exchange was open; records were kept on paper. Today, every element of this has changed: trading decisions are “roboticised”, buy and sell orders are made by powerful computers according to the proprietary algorithms that hedge funds and investment banks have programmed into them.

Record-keeping is computerised and trades are made any time of the day or night. Because computers can respond more quickly than humans, electronic trading platforms have cut the time required to complete a trade to mere milliseconds, which in turn has caused trade volumes to soar.

High speed launch

The high-speed platform launched by the Australian Securities Exchange earlier this year, for example, boasts that ASX Trade “takes ASX’s latency down to 300 microseconds”.

In other words the machines can process 100,000 orders per second, 500 million per day.

Predatory traders constantly labour to discover and “game” the algorithms of opposing firms (the shelf life of an algorithm is now down to 14 days).

As a senior technology analyst at Japanese trading powerhouse Sumitomo Corporation has concluded: it was “a disturbing certainty” this “Brave New World” will lead to “a complete market collapse”.

Stock market crashes were hardly unknown when humans were in charge – the Great Depression of the 1930s is a case in point - algorithmic trading on electronic platforms poses significant new risks to world capital markets.

The interaction of high-speed trading systems processing thousand of orders per second can - and has - created disastrous, uncontrollable feedback loops.

Dramatic plunge

The most dramatic recent illustration occurred on May 6, 2010 when the Dow Jones plunged 573 points in five minutes and dropped close to 1000 points in less than an hour.

And although regulatory agencies around the world have tried to prevent this from happening again by requiring the installation of “circuit breakers” which shut down trading when “abnormal” patterns appear, mini flash-crashes are today a regular occurrence.

Australia has been a relatively minor player in this global poker game until now. But in May 2010 ASIC (the Australian Securities and Investment Commission, Australia’s national regulatory agency), began allowing high speed trading platforms and off-exchange trading here. The ASX immediately unveilled ASX Trade.

The arrival of Chi-X

From October 31, the Australian Securities Exchange will face competition for the first time when Chi-X, a multi-national market operator owned by Japanese investment bank Nomura launches its alternative execution venue. More competition and more market fragmentation, is sure to follow.

Preventing fraud in trades occurring at this speed, in this volume, with this level of programming sophistication and computer power, is what can only be called a significant regulatory challenge.

And regulatory agencies have indeed attempted to meet this challenge. Their main tools have been real-time surveillance systems that monitor stock market trades and signal officials when trading patterns appear abnormal.

One of the most sophisticated is the SMARTS system, devised by Mike Aitken and a group of academics at the Capital Markets Cooperative Research Centre in Sydney.

Their system sets out to measure both market efficiency and integrity. When trading patterns seem to indicate insider trading, market manipulation or other fraudulent acts are occurring, an ALERT is issued and regulators then check it out.

Deterring fraud

The efficiency of such systems in detecting and deterring stock market fraud, however, depends on the sensitivity of the program – too sensitive and a massive number of false positives will be generated; too insensitive and many frauds will remain undetected.

Ultimately, however, the success of these systems lies less in the technological capacity of the regulators (though this is never close to matching the computer sophistication of the regulated) than in their political power.

Only the bravest of regulatory agencies dare intervene in the highly profitable games of Goldman Sachs and their worldwide equivalents when markets are booming.

This has more significant consequences – more potential for wreaking social harm – today than ever before.

Stock dependency

From the 1980s on, governments around the world have been under the sway of neoliberal economic doctrines that mandated the downsizing or elimination of many universal entitlement programs, such as health care, education and pensions.

This made citizens increasingly dependent for their health and wellbeing on savings invested in world markets, usually done through pension (superannuation) funds.

As a result, like it or not, we are all dependent on stock markets now – as demonstrated most dramatically in the 2008 financial crisis when millions lost their jobs, pensions and life chances overnight.

It is incumbent on governments, those who are elected to protect the interests of all their citizens – not just those of the wealthiest 2% – to question what we are all told is technological “progress”; the happy results of traders’ “innovations”.

Which groups are reaping the lion’s share of the benefits? Which are taking the lion’s share of the risks?

In the words of the aforementioned technology analyst, action is necessary “to pre-empt the re-manifestation of greed and the birth of flash mega-recessions”.