TRANSPARENCY AND MEDICINE – A series examining issues from ethics to the evidence in evidence-based medicine, the influence of medical journals to the role of Big Pharma in our present and future health.

Here Adam Dunn discusses his research into authorship networks, which revealed the position of industry researchers in academic publishing.

There’s growing concern that large pharmaceutical companies are capable of undermining the truth about the published evidence doctors use to treat patients. The suspicion is that pharmaceutical companies may be trading lives for profits.

Clinical trials are one of the main sources of information that guide doctors when they treat patients. But controversial drug withdrawals have given doctors good reasons to be sceptical about the evidence that reaches them, and eroded their trust in the evidence base.

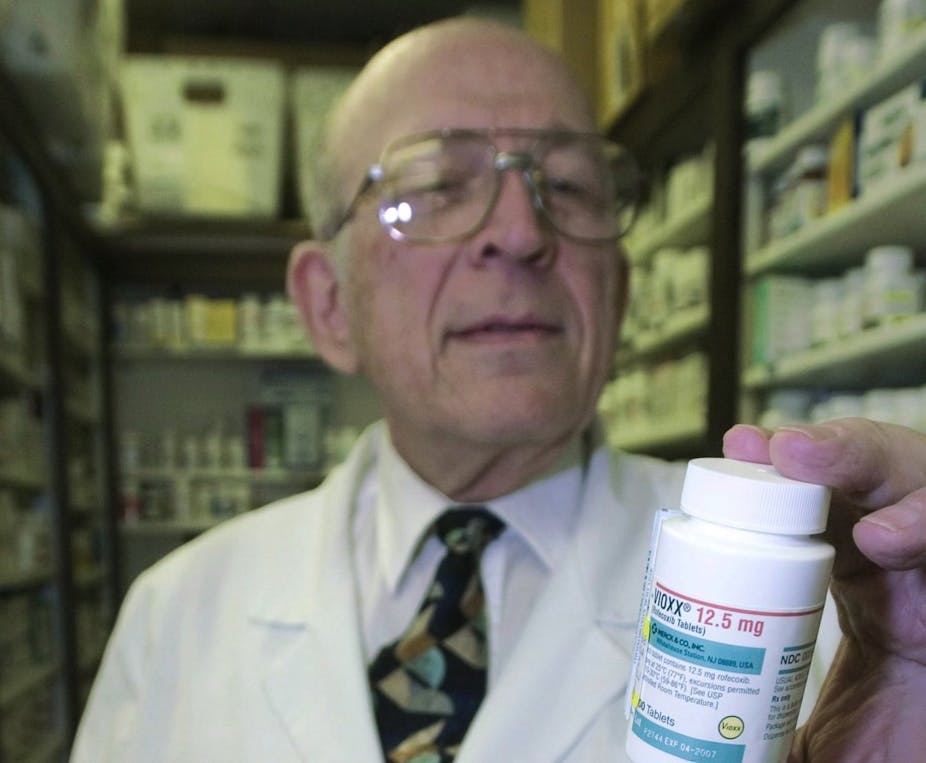

Vioxx gave us the quintessential story of what can go wrong when a big pharmaceutical company exerts influence over the evidence base. The arthritis drug was prescribed millions of times in Australia before it was revealed that it doubled the risk of heart attack. Vioxx was withdrawn in 2003 but the evidence showing its harmful effects was available years earlier.

So when looking for someone to blame, the fingers of prominent academics point directly at the pharmaceutical industry. But are their views justified?

With colleagues from the Centre for Health Informatics, I used network analysis to investigate clinical trial collaboration for a selection of widely prescribed drugs. Much like the way network pictures of Twitter or Facebook are drawn, we connected researchers who had worked together in a clinical trial.

We wanted to see how important each researcher was in their network, especially those who were affiliated with pharmaceutical companies that manufacture the drugs they study.

Our results showed that industry-based authors of clinical trials held more influential positions in their collaborative networks. These authors also received more citations than their non-industry peers.

We concluded that when it comes to clinical trials about drugs, industry researchers occupy influential positions, and their work is more widely cited. These conclusions left us feeling very uneasy about clinical evidence.

It appears that pharmaceutical companies are disproportionately powerful in coming up with the evidence to support the safety and efficacy of their own drugs.

Those familiar with clinical trials might ask how this could happen when clinical trials are registered under strict protocols and published after rigorous peer-review processes. In other words, if clinical trials are so tightly controlled, how can they be manipulated to show a drug is safe when it’s not?

The simple answer is that industry groups do trials differently. Industry-sponsored trials are less likely to publish negative results and more likely to design trials that will produce positive results in the first place. On top of that, industry is responsible for more evidence now than ever before – over a third of registered clinical trials each year are now funded by pharmaceutical companies.

When important evidence is designed to provide only positive conclusions, the data proving a drug’s safety is simply not made available. This is exactly what happened when diabetes drug Avandia was shown to increase the risk of heart failure in 2007. Even after a decade in the market, there were simply not enough data available to show the long-term risks or benefits.

Avandia was a key piece of the evidence puzzle for our research because it revealed the clear and direct negative effect of industry influence. An analysis of articles about the drug revealed that researchers with financial conflicts of interest continued to write favourably about the drug even after the negative evidence was published.

And although Avandia was withdrawn in the United Kingdom and New Zealand, it remains available (albeit under much tighter controls) in Australia and the United States.

So it seems that the lessons from this case may not have been learned. How can we know where and when industry influence will next tip the evidence balance in the favour of another harmful drug?

We’ll need to know more than whether or not clinical trials demonstrate safety and efficacy – we need to know if the right kinds of clinical trials were done in the first place.

This is the eighth part of Transparency and Medicine. You can read the previous instalment by clicking the link below:

Part One: Power and duty: is the social contract in medicine still relevant?

Part Two: Big debts in small packages – the dangers of pens and post-it notes

Part Three: Show and tell: conflicts of interest undeclared for clinical guidelines

Part Four: Eminence or evidence? The ethics of using untested treatments

Part Five: Don’t show me the money: the dangers of non-financial conflicts

Part Six: Ghosts in the machine: better definition of author may stem bias

Part Seven: Clearing the air: why more retractions are good for science

Part Nine: Insight into how pharma manipulates research evidence: a case study

Part Ten: Why data from published trials should be made public

Part Eleven: Open disclosure: why doctors should be honest about errors

Part Twelve: Reaching full and open disclosure for universities, medical schools and doctors

Part Thirteen: Ethics of accepting suppliers’ gifts in the business v medical world

Part Fourteen: Conflicts of interest in guideline development: the NHMRC responds

Part Fifteen: Consumer input in Medicines Australia’s code of conduct review