From Tunis to Oakland, Madrid to Athens and Sydney, an estimated 900 major occupations of public places by citizens took place around the world during the past 12 months. The following notes probe their political significance. With apologies to Marx and his well-known Theses on Feuerbach (1845), they were written for a session of the Sydney Writers’ Festival, held on May 17th, 2012.

First thesis: public occupations are proof positive that small groups of committed citizens can have big effects. Especially in the Atlantic region, against hefty odds, they’ve given a bad name to government ‘austerity’ policies that protect the rich, slash wages, scale back public employment, tear up collective bargaining and let banks and credit institutions off the hook. Occupy politics is a declaration of independence from ‘odious debt’, an insistence that there are times when debts are so foul that citizens collectively have the right to declare them null and void. So the occupations have helped revive ‘the social question’. Talk of rich and poor, injustice and indignation is back in fashion. So is Karl Marx.

Second thesis: understanding occupation politics is a formidable challenge. In his eleven theses on Feuerbach, Marx helpfully suggested that analyses of conflicts over the distribution of wealth must avoid becoming knotted in other-worldly abstractions. Pay attention to the context, he said. Stay close to the ground, stand alongside the flesh-and-blood combatants. Try to understand what they say. So let’s take his advice by giving a twist to his final thesis on Feuerbach: ‘In sympathy with occupy politics, millions demand change, including philosophers, but the point is to interpret the world, without lapsing into mysticism.’

Third, the phrase ‘Occupy Movement’ is a stale mantra. Despite great variations of language, style and tactics in such different settings as Puerta del Sol, Kuala Lumpur’s Independence Square and Zuccotti Park, most activists and observers talk in terms of a ‘movement’, or a ‘motion on the way to being a movement’ (Todd Gitlin).

My fourth thesis: the word ‘movement’ has a questionable history. It’s neither innocent nor timeless nor ‘neutral’. It’s a neologism from the 1840s, when Lorenz von Stein and others first used it as a toponym for making sense of the birth of class politics. This was a period saturated with images of a world in motion. Industrial progress, the spread of European empires, railways, electric motors, the conquest of nature, belief that classes are capable of reading and performing the script written for them by the revolutionary forces of history: the category of ‘movement’ belonged to that era. A fish in its waters, it fed on metaphysical presumptions. ‘It is not a question of what this or that proletarian, or even the whole proletariat, at the moment regards as its aim’, Marx (with Engels) wrote in The Holy Family (1844). ‘It is a question of what the proletariat is, and what, in accordance with this being, it will historically be compelled to do.’ Strange stuff.

Thesis number five: people who today use the term ‘movement’ are usually unaware of its tainted genealogy. In their vocabulary, it functions as a taken-for-granted signpost that warps their worldly perspective. Take an example: the pragmatists who complain that occupation politics has no single narrative, no coherent organisation and no leadership, in effect trash it for failing to act as a movement with a sense of its own political mission. It needs to pull itself together, they say, agree proximate goals, put together a coalition, fashion a single coherent narrative, then elect some representatives who speak on its behalf, positively in its defence. Strangely old-fashioned, pragmatists overlook the novelty of occupy politics.

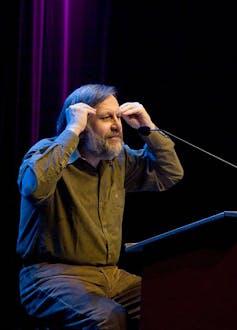

Sixth: certain philosophers, keen to outdo the pragmatists, fancy themselves as the Master Intellectuals of occupy politics. The ‘occupy movement’ is ‘the beginning, not the end’, says the chest-plucking, hirsute, self-styled Marx and Lenin of the 21st century, Slavoj Žižek. He thinks of it as (potentially) a unified force that contains the germs of ‘the truly New’. In the same breath, he chastises its narcissism, treats it like a child, praises its historical potential and expects it to become the Universal Subject-Object. He fancies himself as the dramaturg of a great historical drama. For him, it’s not a question of what this or that activist, or even the whole occupy movement, at the moment regards as its aim. It is a question of what the movement is, and what, in accordance with this being, it will historically be compelled to do. That’s why he insists that the ‘movement’ face the terrible truths: democracy and human rights are bourgeois rubbish. It’s ‘Capitalism’ which ‘is now clearly re-emerging as the name of the problem’, he writes. The Occupy Movement is its solution. Žižek is amusing, but he’s a reactionary clown, a peddler of 19th-century mysticism.

Seventh, occupation politics contains multiple tendencies, diffuse aims and fuzzy edges. It’s a networked carnival of the disaffected. Their protests are infused with a strong sense of performance and satire. When evicted from UC Berkeley, protesters launched helium-filled tents above the heads of riot police; in Sydney, a Guy Fawkes rally featured a large placard: ‘I don’t believe in anything I’m just here for the violence’. The most potent resource of the occupiers is their democratic political attitude: they reject bossing and bullying, they refuse to play the bankers’ and politicians’ game of ‘playing poker with people’s lives’ (Alexis Tsipras). But occupation politics isn’t a movement. The toponym doesn’t fit its topography, which is more complex, more fluid, more interesting. Occupation politics has antecedents. It recovers the spirit of Make Poverty History and the Battle of Seattle; and it’s a creative remix of some earlier democratic inventions, such as the peace vigil, the civil rights sit-in and the student teach-in.

Eighth thesis: occupy politics is a child of the age of communicative abundance. Harnessing the latest tools of communication, its gatherings resemble multi-media broadcast studios, lighthouses, early warning stations, loud cries to the world by witnesses who know its sufferings. Occupation politics may feel ‘utopian’, but it’s a high-tech and down-to-earth media forewarning of how easily democracy is destroyed by unfettered markets, great inequalities of wealth, the fetish of consumption and the arbitrary ‘thieving’ power of elected governments, banks and credit institutions. The occupations are monitory democracy in action.

Ninth thesis: occupy politics cannot side-step questions about political representation. Despite efforts to practise ‘liquid democracy’ and new forms of finger-wiggling ‘consensus’ and ‘non-violent direct action’, the tricky business of ‘who represents whom’ within its own ranks lingers. There’s another reason why the subject of political representation can’t be avoided: anger and indignation are not enough. Occupation politics is vulnerable to official manipulation and repression. Self-protection against these forces thus requires finding coalition civil society partners, outflanking political parties, influencing election results and forcing parliaments to change course. If citizens are serious about ‘taking back their institutions’ (Beppe Grillo), they need more than action at a distance. Occupy politics implies the ‘occupation’ of representative institutions.

Tenth thesis: the occupy initiatives foreground the frightening build-up of state violence in all actually existing democracies. To occupy (originally from the Latin occupare) is to seize a place, often without warning, for the purpose of turning it into something other than what it was, to transform its significance. Occupation using peaceful methods automatically disrupts power relations and wins the moral high ground. That’s why political authorities feel threatened and why they fight back, initially with smooth words and firm warnings. Sooner or later, they reply with steel cordons, truncheons, tear gas, rubber bullets, water cannon, drones, or troops. The trending Twitter hashtag of the Spanish indignados, #HolaDictadura (Hello Dictatorship) captures the point: occupation politics teaches us that democratic ideals now come encased in high-tech surveillance and repression.

Is there an eleventh thesis? Marx thought so, but why not instead treat it as an open space, to be occupied by others?