My favourite Freudian idea is omnipotence of thought. It explains everything from superstition to lucky charms to OCD and it’s what’s “new” about cash cows like The Secret.

That our thoughts are powerful enough - are magical enough - to change things.

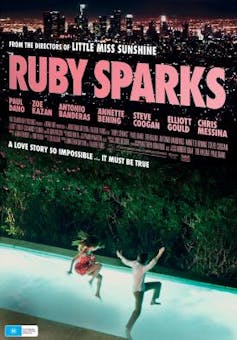

As a writer, the idea that thoughts, that words, could have such power is thoroughly seductive. Seductive and oh so very self-indulgent. And it’s the premise of Ruby Sparks.

Neurotic wunderkind novelist Calvin (Paul Dano) dreams about the perfect girl, types her up and just like magic she appears. In real life. In all her flame-haired, coloured-stocking, blow-job-enthusiast glory.

So I really hate the what do you want question as related to relationships. Equally do I loathe the what do you like question in regards to sex. I don’t know how to answer either. There’s too many ifs and buts and variables.

And I was thinking about these questions - about my inability to answer them - while watching the preview for Ruby Sparks a couple of weeks ago. Calvin’s powers lacked appeal for me because I don’t know what I want well enough to type it.

The handful of times I’ve desperately crossed-my-fingers wanted something and when I got it was, often, horrible. I write this not merely as support for the be careful what you wish for adage, but more broadly because I don’t think it’s possible to wish with sufficient accuracy or specificity.

How do you type up wanting love, wanting to be needed, wanting copious amounts of affection but also manage to accurately identify all those on-my-terms and in-palatable-doses-only caveats?

How do you specify wanting the dream partner to appreciate your work, to satisfy you sexually, to find you hilarious, but also manage to make them forget that they’re only doing it because you’ve forced them?

I went into the cinema over the weekend convinced that I wasn’t interested in Calvin’s superpower because I don’t trust my imagination or skills as a writer. I left the screening convinced of it for quite a different reason.

Philosopher Pierre Bourdieu has a line about taste being born from what we’re “condemned to”. While Ruby Sparks makes no overt references to Bourdieu, his idea pervades the film: that we can only ever have an appetite for what we know.

That our vision of the perfect partner at most is a version of ourselves.

Calvin can only fantasize about the perfect girl by using the points of reference he has. He can give her traits that his previous girlfriend didn’t possess, perhaps gift her qualities he’s desired but never experienced, but the ideas are still only drawn from the finite pool of what he knows; from what he thinks he has a taste for.

To me this idea explains my complete befuddlement when trying to answer the what do you want/what do you like questions. How can they be answered when embarking on anything new? How does anyone know what they like when with someone they’ve never been with before?

The other day I clicked on a Fairfax blog post which - in far too much detail - pitched a a road map to the G-spot. More interesting than the post however, was one of the reader comments:

I dont really buy all these “twiddle knob A, push button B while operating flange C” style things…You should just fool around and see what she likes

Encapsulated in this comment is the key to working things out in the bedroom, but more so, in life. And it explains why Calvin’s “gift” turns out to be such a disaster. There’s what you think will work in theory - on paper - and then there’s just seeing how things go. Without the lists and the planning and the obsessive orchestration.

Like Garden State, like High Fidelity, like Me and You and Everyone We Know, like Synecdoche, New York - films I loved but which nevertheless tried very hard to be cool - sometimes Ruby Sparks felt laboured. But I liked it. Despite myself I liked it.

I am, afterall, a sucker for ever newer lenses to examine my neuroses.