MEDIA & DEMOCRACY: Today, Anne Tiernan looks at how voters have become consumers of political marketing, as part of The Conversation’s week-long series on how the media influences the way our representatives develop policy.

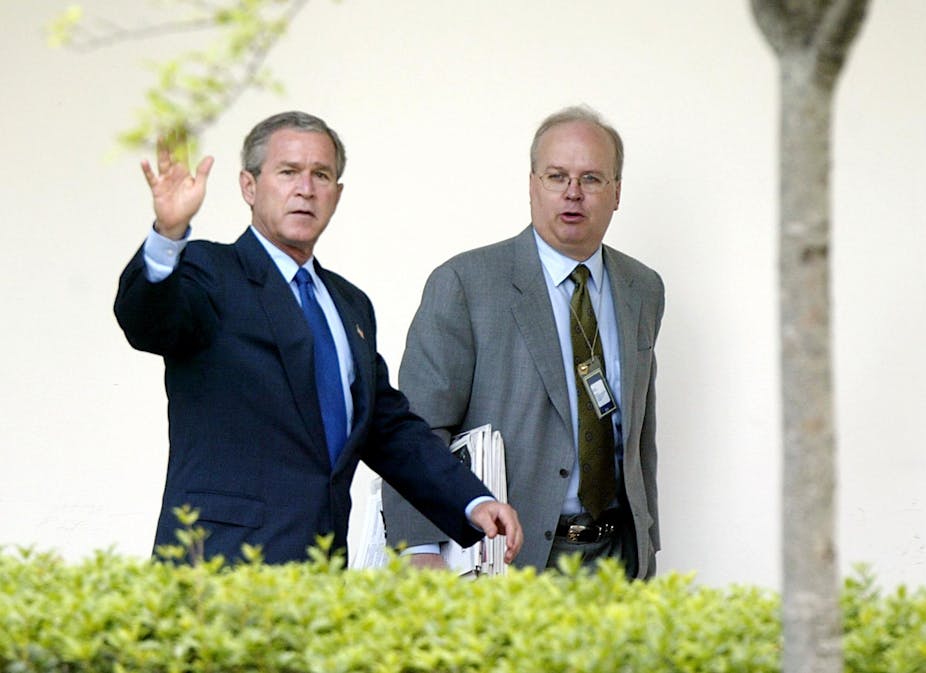

Karl Rove was known as President George W Bush’s “brain”. Alastair Campbell has admitted insisting that a controversial dossier of evidence published in the run up to the Iraq War had to be “revelatory”, and it became a persuasive document for the allied forces’ attack.

Between them these two political advisors made a significant contribution to changing the course of recent history. But should they have been able to? Should political advisors be able to control their democratically elected masters?

The Conversation spoke to Associate Professor Anne Tiernan of Griffith University to examine what whether democracy is at risk from those closest to those in power.

Is the power of advisors increasing or has it reached a zenith?

The power of advisors is delegated and they exercise authority on behalf of their ministers - in their minister’s name. This is one of the complicated things about the role of the advisor. It’s often not well understood that, theoretically at least, they have no independent status or authority.

They are an extension of their minister; a surrogate if you like. Our system assumes that any instruction they give or any decision they might take has their minister’s authorisation and that their minister has knowledge of and approves it.

But there are practical issues here. How realistic is it to expect that busy ministers have the time or capacity to closely monitor and supervise their staff, when as we know, recent governments have employed quite large numbers of ministerial staff. It is of course difficult to know whether a staffer is acting for their minister and with his/her authorisation, or on their own behalf. There have been some well known cases of staffers going beyond the limits of their authority - perhaps in their dealings with public servants, for example. When a minister says “I wasn’t advised”, but in fact a member of their staff was told something; or claims not to know a member of their staff was acting in a particular way, there is a problem of accountability.

Ministers are accountable to parliament, and public servants answer to parliament through ministers - we have ways of handling that. But staffers aren’t accountable to anyone except the minister and if the minister walks away and refuses to accept vicarious responsibility for their actions of their staff, that leaves a vacuum of accountability that can’t be resolved. Both sides of politics have been unwilling to allow ministerial staffers to appear before parliamentary committees because it would afford staff a status that they don’t and can’t really have - independent of their minister.

There was a quite torrid debate about this during the Senate inquiry into the “Children Overboard” affair. A subsequent Senate inquiry into the role of staff employed under the Members of Parliament Staff (MOPS) Act, made a number of recommendations that were subsequently adopted by the Rudd government when it won office in 2007. These included the suggestion from former Chief of Staff to Prime Minister Paul Keating, Dr Don Russell, that in a situation where a minister walked away, and refused to accept responsibility for the actions of their staff, that the chief of staff could be called [and be accountable for decisions].

Now, that hasn’t been tested but that recommendation has been adopted as policy by the government, federally. And we haven’t seen as much contention about the role of staff more recently as we did during the Howard years.

Do we have the rise of the political class where the advisors see what they are doing as a step to a safe seat?

It is important to understand that there are different types of roles within ministerial offices and many different kinds of people working in them. There is a bit of nuance about that and I prefer not to generalise. Broadly though, most offices have policy people, who may or may not have a substantive background in the minister’s portfolio; political and issues manager types who might handle relationships with the party, for example; there are media and communications people who tend to come from journalistic or public relations backgrounds. Then there is a group of administrative and support people who handle appointments, invitations, correspondence and so on. Experienced administrative staff are highly sought after; sometimes they work for one minister and then the next. It sounds obvious, but having good staff is incredibly important - as much because it creates the perception of ministerial effectiveness and competence, as well as the reality.

How many staff there are depends on the minister’s position: cabinet ministers have more staff than junior ministers; the Prime Minister, Treasurer and senior ministers have more staff and they’re more senior as you would expect. The mix of staff and skills required depends on the portfolio, but it also reflects what the minister him/herself wants and feels will suit their preferences and working style.

Not everyone who works in a ministerial office has political aspirations but it is clear that many of the people who go on to achieve pre-selection have come through a policy advisory or media advisory type and yes, it is absolutely a stepping stone to pre-selection in those cases.

You can look down the federal front bench of both sides of Australian politics and very many of them spent time working in what I would call para-political roles. Gillard was, Abbott was, Hockey [was](http://www.joehockey.com/meetjoe/default.aspx.

There are contending views about the desirability of this. Some people think that politics is a professional game and you really have to have the knowledge and skills to know how to operate effectively in it. Others are concerned that people are coming from a very narrow career background to these roles and both Labor and the Coalition have asked themselves at the party level whether this is a good thing.

Howard raised questions about this when he was Prime Minister about the narrowing of the political gene pool, as he described it, and said he didn’t think it was a good thing.

Other people say how would you know how to do that work unless you’d come through some sort of professional training because there is no training to be an MP or a minister.

How much influence do advisors, particularly media advisors have? There are a lot of popular culture representations of this. How accurate is that?

The simple answer is it depends: it depends on the minister and it depends on the staffer. Good ministers who know what they want to do and are policy focused aren’t going to be run by anybody, but they might have somebody who becomes quite important to their performance.

Take for example, the way the role of the Prime Minister’s Chief of Staff has evolved. It has become very important. You’d have to say that Arthur Sinodinos is regarded as having been a very effective chief of staff to Prime Minister Howard. He was integral to Howard’s performance as PM and pivotal within his system of advice.

Did Arthur Sinodinos run Howard? I don’t think anybody ran Howard except John Howard. So how much influence did his people have? Decision makers will test out ideas, they’ll bounce ideas off people, that sort of thing. How much influence? It is impossible to know. It can change over time. An inexperienced or weak minister may be heavily influenced, but political leaders control for this. They oversee the appointment of staff through various arrangements. They make sure, for example, that an experienced senior staffer is available to help and support a new minister; to “mind” one the leader doesn’t necessarily have full confidence in; or can help out a minister in a difficult portfolio. Those arrangements are increasingly sophisticated in Australia. There’s been a lot of learning about the importance of staff selection and management.

After the resignation of Andy Coulson as the British Prime Minister’s Director of Communications following the News of the World scandal, David Cameron introduced a policy of only employing civil servants as his strategy advisors. Would that work in Australia?

That would be going back to an old model. In the Australian context the whole purpose of the development of the advisor’s role was to have someone to be political support to the minister. You can argue that it has actually reduced the risk of the public service becoming politicised.

If the media advisor is out there spinning - putting a positive spin on what government is doing, as often they do, and they were a public servant, that would I think raises questions about their professionalism and impartiality, which is what we expect of a career public service. I think an incoming government would have very real, and valid, concerns about that public servant’s ability to serve an alternative government.

There are official spokespeople for departments in Australia. Often they are an expert, the Chief Health Officer or Chief Veterinary Officer, for example. Media spokespeople for ministers tend to be political staffers: press secretaries or media advisors, and you’ll note they are rarely named - they speak on behalf of the minister. Putting a public servant into an advocacy and a selling the government’s message type role would, I think, be a fatal step. Our model has more to recommend it because when someone is out talking on behalf of Prime Minister Gillard or the Treasurer, you know that is the Treasurer’s line. To have a public servant doing it would be very problematic in my view.

It’s difficult to draw comparisons between the UK and Australia when it comes to political staff and the public service. The two models are very, very different. Take for instance the issue of ministerial staff. The number of special advisors (or SPADs as they’re known there) in the UK is very small, many, many fewer. Our numbers are up over 450 federally where they have about 80 in the UK and the ministries are lot bigger over there.

Will there be questions flowing from the relationship Andy Coulson had with Cameron?

Certainly. But can you think of the last senior serving gallery journalist who went to work for a minister in Australia? They don’t tend to. There was tendency in the 70s and 80s but that has been very much less the case now in my observation.

The well documented case in Australia is Greg Turnbull. It was very hard for him to go from working for Labor back to the gallery because the then government felt that he was a political actor who had shown his colours and they weren’t going to get fair treatment. Was that fair? Probably not. But when Turnbull went back to the Ten Network it made his job very difficult and Howard didn’t go on Meet The Press for a long time. I think political journalists are less likely in a more adversarial political context to do that.

Why do we have so many advisors?

The staffing system has its formal origins in the Whitlam government and it has expanded under successive governments. Each government that comes in promises to the cut the numbers and they do for a while: Howard did, Rudd did, and pretty soon they find it hard to manage the business of government given the multiple demands. So the numbers creep back.

We have so many because ministers are overloaded and because there is an enormous demand and focus on ministers in our system. Everything coming down the funnel for decision-making lands on ministers’ desks and increasingly, the Prime Minister’s desk. So it’s worth asking whether the numbers of staff really are so big in the scheme of things? We have 42 ministers and parliamentary secretaries and the average allocation per cabinet minister is about 10 staff. That includes a chief of staff, policy advisors to shadow each part of the department, a media person, administrative support. Is that really so many? Some people think so.

Numbers are less significant than accountability issues about where they fit in, how they work with the public service, the impact they have and the quality of advice they give to ministers.

The Rudd administration did a review of government staffing numbers in 2009 that laid out what I think is a really good formula developed by bipartisan agreement.

This is the seventh part of our Media and Democracy series. To read the other instalments, follow the links here:.

Part One: Selling climate uncertainty: misinformation in the media

Part Two: Forget the fantasy politics - advertising is no substitute for debate

Part Three: Democracy is dead, long live political marketing

Part Four: Selling the political message: what makes a good advert?

Part Five: Drowning out the truth about the Great Barrier Reef

Part Six: Event Horizon: the black hole in The Australian’s climate change coverage

Part Seven: Spinning it: the power and influence of the government advisor

Part Eight: Cops, robbers and shock jocks: the media and criminal justice policy

Part Nine: Bad tidings: reporting on sea level rise in Australia is all washed up

Part Ten: Big money politics: why we need third party regulation

Part Eleven: Power imbalance: why we don’t need more third party regulation

Part Twelve: Scientists vs farmers? How the media threw the climate ‘debate’ off balance

Part Thirteen: Warning: Your journalism may contain deception, inaccuracies and a hidden agenda

Part Fourteen: The hidden media powers that undermine democracy