It’s no secret that prisoners inject drugs. And because they don’t have access to sterile needles, inmates not only share needles – they share infectious diseases as well.

The ACT government is currently deciding whether to trial a program to distribute sterile needles and syringes to prisoners. But the Community and Public Sector Union (CPSU), which represents prison guards, is fighting the introduction of such a program, saying it doesn’t want to facilitate illicit drug use and expose officers to potential needle stick injuries.

Spread of infection

Hepatitis C is a virus that causes inflammation of the liver. It’s present in the blood and is transmitted by blood-to-blood contact. Some people are able to clear the virus from their system but others can develop serious complications such as cirrhosis and liver cancer.

Hepatitis C is a significant public health issue, with more than 259,000 Australians estimated to be infected with the virus.

More than 40% of Victorian and New South Wales prisoners are infected with hepatitis C and the proportion may be higher in other jurisdictions.

Prisoners suffer poorer health than the general population and the common life experiences of inmates include sexual victimisation, physical and emotional maltreatment, and suicide attempts by significant others.

Illicit drug use

Drug use occurs within prisons in spite of correctional authorities searching visitors and staff, testing prisoners for drugs, using sniffer dogs and, in some states and territories, offering drug substitution programs and detoxification.

An evaluation of drug policy and services in the ACT’s only full-time adult correctional centre, Alexander Maconochie Centre, found almost one third of inmates reported having injected illicit drugs while in the centre. The facility has been operating for less than two years.

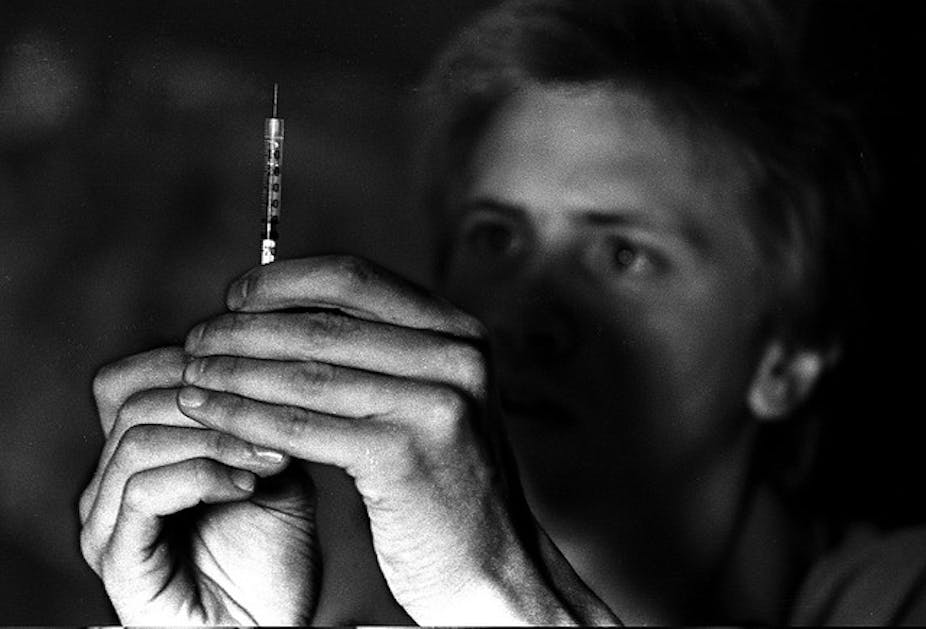

Needles and syringes are shared within prisons in a process that one informant to the Regulating Hepatitis C report described as dangerous, unsterile and clandestine.

A 2009 survey of prisoner health noted that of 112 prisoners who reported injecting, only three used a new needle. This implies the other 109 prisoners were at risk of being infected with a blood borne virus such as hepatitis C or HIV.

Minimising harm

Unlike many other countries, Australia has a pragmatic approach to drug use. The government’s blueprint for reducing the impact of drug use, the National Drug Strategy, wants to reduce the supply and demand of drugs but acknowledges that in spite of doing this, people will continue to use illegal drugs.

All levels of government support the National Drug Strategy’s harm reduction interventions, including the distribution of sterile needles and syringes. But so far this hasn’t translated to establishing a prison-based needle and syringe exchange program in any Australian state or territory.

Similar provisions are made in ACT legislation. The preamble to the ACT Corrections Management Act 2007 notes detainees should have access to health care that is equivalent to community standards and that conditions in detention should “promote the health and wellbeing of detainees”.

There are various other regulatory instruments at a national, state and territory level that support the distribution of sterile needles and syringes, including statements from the Correctional Administrators from each state and territory who note “each prisoner is to have access to evidence based health services”.

The wrong fight

There is substantial international evidence to support the safety and efficacy of needle and syringe programs in correctional settings.

A review of interventions to reduce the transmission of HIV in prisons, published in The Lancet, found prison needle exchange programs reduced the sharing of needles and syringes. The programs halted the spread of HIV and hepatitis (with no new cases found) and improved staff safety. There was also a reduction in overdoses.

The resistance to a prison needle exchange program in Australia reflects a culture within correctional services of being tough on prisoners.

Prison officers also have an uneasy history with injecting drug users since the death of prison officer Geoff Pearce, who was stabbed by a syringe filled with HIV-infected blood in Long Bay Gaol in 1990.

While some officers are breaking rank and calling for a trial needle exchange program, the CPSU seems unlikely to back down. A statement in its employment agreement with ACT custodial officers states that “for the safety of staff, no needle exchange program, however presented, shall be implemented without prior consultation”.

The ACT Government is expected to make a decision by the end of the year about whether to trial a needle and syringe exchange program.

I hope it considers all the evidence and sees this decision for what it is – a human rights and health services issue that could reduce the spread of hepaptitis C in the prison community and the wider population.