One touch and you’re infected. By the next day your muscles ache, you have a fever and the beginnings of a headache.

You don’t know it yet, but you only have a one in three chance of survival and you’ve already infected three other people. Two weeks later, 8 million people have been infected.

This is the scenario presented by Steven Soderbergh’s latest film Contagion, but is it pure fantasy or an alarm bell, a warning of a devastating future?

Making it real

The creators of Contagion, writer Scott Z Burns (screenplay writer for The Informant and Bourne Ultimatum) and director Steven Soderbergh (director of Traffic and the Ocean’s trilogy), were determined to illuminate the potential catastrophe of a worldwide pandemic as realistically as possible.

To do this, they employed a number of technical consultants from the field of medical research, including Walter Ian Lipkin, a professor of epidemiology, neurology and pathology at Columbia University, whom they asked to design the virus that would cause the pandemic.

An expert in his field, Professor Lipkin was recruited by Chinese officials to help curb the spread of SARS during the 2003 outbreak in China in which 8000 people were infected and 750 people died.

Professor Lipkin recently wrote about how he had been approached by several movie-makers over time, but before the Contagion team, none had convinced him that they genuinely wanted to make a movie that “… didn’t distort reality but did convey the risks that we all face from emerging infectious diseases.”

The virus

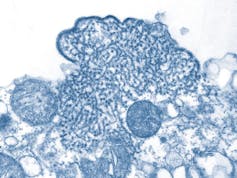

Lipkin and his research team decided to base their fictional virus, MEV-1, on the very real and deadly Nipah virus.

The Nipah virus infected 265 people in Malaysia between late 1998 to mid-1999, with a 40% fatality rate. Since then, it has caused 12 separate outbreaks, mainly in Bangladesh but also within Singapore and India.

In some of these outbreaks, every infected person died.

Initially transmitted from infected pigs to humans through direct contact, strains of the virus have since mutated, enabling much more dangerous human-to-human transmission.

Emergence of disease

Within infected humans, Nipah virus causes respiratory difficulties but can also induce an often-fatal inflammation of the brain, known as encephalitis.

Signs of illness begin with influenza-like symptoms of fever, sore throat, headaches and muscle pain, progressing to dizziness, altered consciousness and neurological signs that can include fits – such as those prominently depicted in the trailer.

In Contagion, the virus originates from Hong Kong, a not unlikely scenario given the first SARS outbreak centred there.

Many different diseases (known as zoonotic diseases) that have similar modes of transmission – from animals to humans – have come from neighbouring South-East Asian countries.

Among others, they include Nipah virus and swine flu.

A high mortality rate is very real for these viruses, but could millions of people really become infected? And could it spread beyond Asia to wreak equivalent havoc in Western countries, such as America, where most of the film is based?

Global reach

Viruses spend their life replicating. Some, such as cytomegalovirus, can shed more than a million viral particles within a drop of saliva.

Viruses such as rotavirus need as little as twenty viral particles to effectively infect a person and make them very ill.

According to the International Air Transport Association, there were 750 million scheduled international flights taken worldwide in 2010.

So it’s not beyond the realms of possibility for such a virus to spread to disparate regions of the world within weeks.

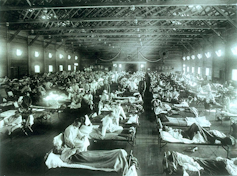

The 1918 Spanish influenza outbreak (mentioned in the film) is thought to have infected 30% to 40% of the world’s population at that time.

Conservative estimates put the death toll attributed to this strain of influenza at 50 million people. At the time of that pandemic, the aviation industry was only just beginning.

So a virus infecting and killing millions of people worldwide is not only feasible, it’s happened before.

Elusiveness of cure

But don’t the current worldwide surveillance of outbreaks, more advanced medical research capabilities and modern healthcare infrastructure, make a repeat of a pandemic like the Spanish flu, or the fictional MEV-1 of Contagion beyond the realms of possibility?

Unfortunately, no. The increasing encroachment of people into previously uninhabited areas, in addition to unhygienic animal husbandry practices in many South East Asian countries, means new viruses are now being introduced into the human population.

Early mutation of such viruses could give rise to human-to-human transmission, and it could easily spread before any surveillance organization has a chance to notice an emerging pocket of disease.

In fact, the detection of the MEV-1 virus in Contagion, its identification and the resulting global co-operation to curb its spread is in many respects the best-case scenario.

Even though the real Nipah virus had its first outbreak in 1998, a vaccine for it has not yet been developed. Nor are there any effective anti-viral drugs for treatment of symptoms in the current treatment protocol.

Have Steven Soderbergh and Scott Z Burns created a realistic pandemic movie? It’s the most realistic I’ve seen, and certainly not beyond the realms of possibility.

Can reality be scarier than fiction? Absolutely.