Three weeks before the Olympics, Swimming Australia imposed a new “high-performance” funding model on its swimmers, reportedly to “see medallists rewarded”. The timing made it difficult, even unpatriotic, to question the new model but in the wash-up after the Olympics, it warrants scrutiny.

The new model meant swimmers received a low base rate for participating and then a sliding scale of bonuses depending upon their performance. These performance bonuses ranged from $35,000 for individual gold medals to $4,000 for 8th position … and nothing for less than that.

The model is profoundly revealing in two ways. First, it highlights the extent to which an economic understanding of human motivation has permeated all corners of Australian society.

Second, it starkly demonstrates the limitations of financial incentives in achieving outcomes. The model failed. It is generally agreed that the Australian swimmers performed well below expectations.

An economic understanding of human motivation has been steadily gaining ground in English-speaking countries for a long time. The pioneer of this approach was Gary Becker, a Professor of Economics at the University of Chicago. In the 1980s Becker argued that human beings essentially run a cost-benefit analysis on all of their decisions, and act accordingly.

Becker proceeded to apply this logic to marriage and the family, crime and punishment, and discrimination against minorities. He argued people “marry when they expect to be better off than if they remain single, and they divorce if that is expected to increase their welfare”. In 1992 Becker was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economics for his efforts.

Becker’s analysis inspired the application of the economic approach to all fields of human behaviour. It informed public policy – neatly illustrated in the constant reference of government ministers to the “business model” of people smugglers, and in the finely calibrated compensation packages for the carbon pollution emissions scheme. And it permeated popular culture, illustrated in the blockbuster Freakonomics franchise.

An economic understanding of human motivation provides important insights into aspects of human behaviour, but is profoundly limited nonetheless. Above all, it does not take into account our sociability.

Human beings are intensely sociable animals. We are more like chimpanzees than orangutans, and more like dogs than cats. We seek each other out, we congregate together, we rely on each other, we check each other out, we copy each other, and we compete against each other. The Olympics are a social event on a global scale.

There are two ways in which our sociability shapes our motivation. First, it shapes our character. Our character is formed in the crucible of our families. Humans are unique among all animals in the length of our dependency. This means there is unique scope for social learning.

Olympic athletes almost invariably acknowledge their parents when they win their medals. Swimmers thank their mums and dads for getting up early every morning and driving them to training in their early years. For encouraging and supporting them every step along the way. For making them into the champions they have become.

I’m not convinced young swimmers do a cost-benefit analysis of becoming an Olympic champion. Not least, the rewards do not match the investment. Rather, I suspect they swim because their parents and those whom they love and respect encourage them to swim, and praise them for their efforts.

Our sociability also shapes our motivation insofar as we care about what others think about us. We are motivated by praise and peer pressure. We are motivated by the prospect of criticism and humiliation. And we are motivated by the prospect of glory. The Olympics offers all of these things in abundance.

Instantaneous media coverage and social networking websites intensify the feedback loops. The moments of glory and humiliation occur in the glare of a global spotlight, for all to see. No wonder swimmers and other athletes seem more relieved than anything else when they meet expectations and win gold!

In this context, the high-performance funding model seems grotesquely feeble. Did Swimming Australia really imagine swimmers would swim harder because of its incentives? Did it really imagine it would boost the medal tally?

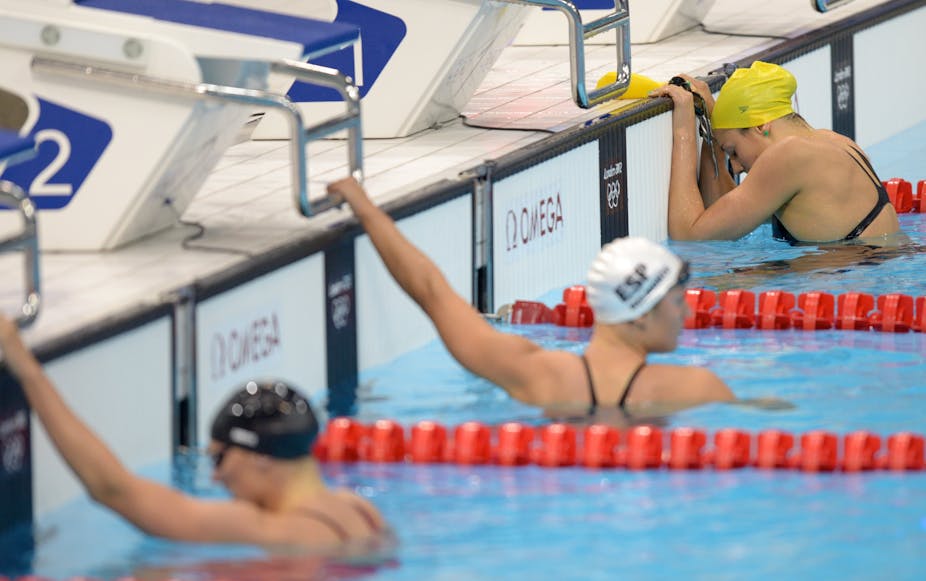

But the model was perhaps worse than feeble. The swimmer Brenton Rickard said it was a distraction. Daniel Kowalski, the head of the Australian Swimmers’ Association and a former Olympic medallist, said it was disrespectful. The implication here is that the model may have corroded the Olympians’ motivation and performance.

We will never know if the model actually had this effect or not. What we do know is that the model failed. The swimmers had their lowest medal tally since the 1992 Olympics, notwithstanding the record-holders in their midst.

It would be nice to think that the people responsible for the high-performance model are paid a low base rate for their efforts, with a performance-based bonus. Sadly, I’m pretty sure that won’t be the case.