Have you ever driven through an intersection, only to wonder 50 metres down the road whether the traffic lights were indeed green?

How about meeting someone at a party, having a rather enjoyable discussion and then realising that when you shook their hand at the start of the conversation you took absolutely no notice of what their name was?

The world is so chock-a-block full of information that it’s no surprise that many things slip under our radar - even if those things can put you at serious risk of a (social or literal) car crash.

The same principle applies to nursery rhymes.

Have you ever actually listened to the words of these little ditties? Gruesome. Ghoulish. Ghastly! Even those couplets with words so sweet and innocent that you couldn’t possibly believe there was a nefarious origin….think again. Take this well-known verse as an example:

There was an old lady who lived in a shoe,

She had so many children, she didn’t know what to do.

At first glance, the social commentary in this rhyme extends, at most, to urging the use of birth control when one lives in a confined space (say, a shoe). A sound lesson, to be sure. But take a look at the next two lines:

She gave them some broth without any bread;

Then whipped them all soundly and put them to bed.

Yikes. With no more than several twists of the tongue, we’ve crossed several lines of propriety, and raised the concern of child protection authorities. I wouldn’t recommend the old lady for baby-sitting duties.

Of course, nursery rhymes have a perfectly legitimate need. The rhythmic patterns provide an ideal framework for infants and children to develop language, which we’ve explored in a previous column. But why choose these words, when any words would do?

This fortnight, I’ve had a bit of fun trawling through nursery rhymes and researching their astonishingly grizzly roots. I’ve listed below my three favourites. While there is little conclusive evidence for the definitive origin of these three nursery rhymes, I’ve searched high and low to provide the best guess of many scholars (yes, there are nursery rhyme scholars!).

Mary Mary quite contrary

Mary, Mary, quite contrary,

How does your garden grow?

With silver bells, and cockle shells,

And pretty maids all in a row.

I read this nursery rhyme and drift to an image of a sweet old lady tending lovingly to her flowers. Oh, how I wish!

The Mary in this verse, the scholarly books read, refers to Mary Tudor: Queen Mary I of England (b 1516). For those not completely up to speed on their Tudor history, Mary was the only surviving child born to Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon. Henry, ever the SNAG, became impatient with his lack of male heir and decided that he’d like the marriage annulled so that he could try and produce the next King with another woman (he, of course, had his eye on Anne Boleyn).

At that time, England was a Catholic country and required the permission of the Pope for any marriage to be deemed invalid. Pope Clement VII - by all reports, a rather fearsome bloke – denied Henry this request, which royally upset the King and set in place the events that would lead to England breaking away from Rome, and the formation of the Church of England.

Henry VIII died in 1547, and the monarchy was passed to Mary (after a brief stint with her rather sickly half-brother, Edward VII, who died when he was 15). Mary, no doubt a little miffed at Henry’s treatment of her mother, remained loyal to Catholicism throughout her years in exile, and was intent on restoring England to this faith. But the clergy and nobleman weren’t too pleased with yet another change, and proclaimed that Protestantism (Church of England) was the rightful religion of England, and that Mary could go jump in a lake.

Mary got mad – indeed, she got very mad – and passed legislation that would punish anyone judged guilty of heresy against the Catholic faith in the most grisly of ways (Hint: her nickname was Bloody Mary).

It is at this gruesome point that we go back to the nursery rhyme. The garden refers not to a lovely England cottage overcome with bloom, but rather to the cemeteries that were becomingly increasingly full of Mary’s victims. The silver bells and cockle shells refer to her favoured instruments of torture - the former being thumb screws, and the latter being screws that are places on…umm…other parts of the male anatomy. Finally, the ‘maids all in a row’ is a short-hand reference to the guillotine (nicknamed ‘The Maiden’), which Mary also didn’t seem to mind using on her enemies.

I bet you wish you didn’t know that.

Three blind mice

Three blind mice. Three blind mice.

See how they run. See how they run.

They all ran after the farmer’s wife,

Who cut off their tails with a carving knife,

Did you ever see such a sight in your life,

As three blind mice

These lyrics don’t exactly conjure up the serenity of an innocent reading of ‘Mary Mary Quite Contrary’, but the hypothesized origin of this tale is even more gruesome. Again, this nursery rhyme is thought to refer to Mary I, and again, it doesn’t cast her in the best light.

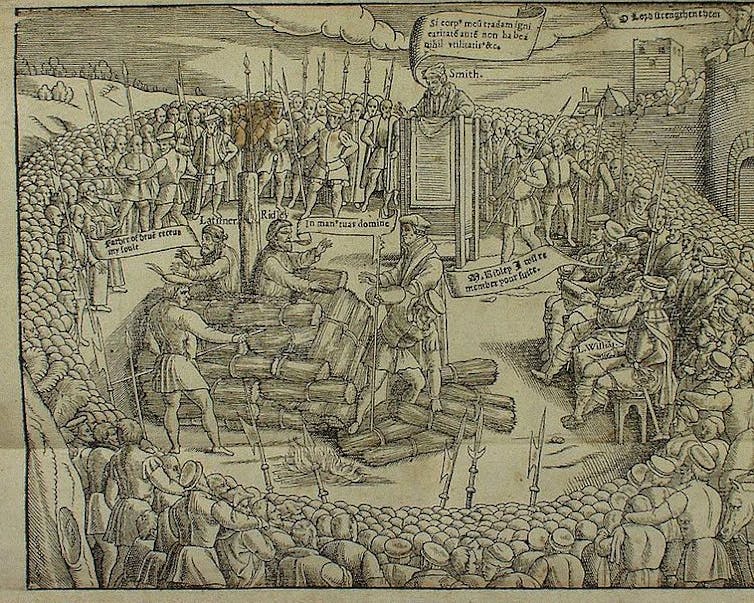

Thomas Cranmer was an influential clergyman of the early 16th century, and a bit of a pain in the neck to Mary. Henry VIII appointed Cranmer as the Archbishop of Canterbury, and even after Henry’s death and Mary’s ascension to the throne, Cranmer flew the flag for the Church of England. This, of course, was a big mistake given that Mary was rather active in crushing any voice of dissent. She threw Cranmer in jail with two other Anglican Bishops, Hugh Latimer and Nicholas Ridley, and roundly burnt them at the stake. There is a plaque on Broad St in Oxford marking the site of this ghoulish event.

‘Three blind mice’ is thought to be a reference to Cranmer, Latimer and Ridley. Mary I was married to Philip of Spain, who had vast land holdings throughout Western Europe, and thus ‘the farmer’s wife’ refers to Mary herself. The big spanner in the works for this interpretation of the nursery rhyme is that the Bishop’s weren’t actually blinded (which was a charmingly common form of torture in the 16th Century). However, it is argued that the blindness may be a little dig at the Bishop’s Protestantism.

Humpty dumpty

Humpty Dumpty sat on a wall,

Humpty Dumpty had a great fall.

All the king’s horses and all the king’s men

Couldn’t put Humpty together again.

Fast forward a hundred years, and the English monarchy itself was under threat. The Royalists (Cavaliers), who were loyal to Charles I, were coming under attack from the Parliamentarians (Roundheads), who fought for Oliver Cromwell against the rather overbearing policies of Charles.

In 1648, the Royalists were on a whistle-stop tour of eastern England to recruit men for the upcoming war, and they stopped at Colchester, a small town in modern-day Essex. The Parliamentarians tracked their enemies to Colchester and forced a siege which lasted 11 weeks.

During the siege, the Royalists had a large cannon that was placed on a strategically important flank of the town’s wall. The cannon’s nickname was ‘Humpty Dumpty’. At the final battle that forced the end of the siege, the Parliamentarians attacked the wall supporting Humpty Dumpty, and the cannon fell to the floor, breaking into pieces. Legend has it that the nursery rhyme was used as a way for Crowell’s army to communicate the news around the divided nation. (The first allusion to Humpty being an egg wasn’t until the 19th Century)

Postscript: In somewhat of an ironic turn, the nursery rhyme that most people believe has an unpleasant origin - Ring a ring o’ roses - has actually very little evidence connecting it with the bubonic plague. Many scholars believe that the link was merely the work of 19th Century conspiracy theorists - as indeed may be the three interpretations that I’ve presented above. Let the debate rage on!

Click here if you would like to be on the mailing list for this column.