There is no excuse for Indigenous education in Australia to be in such a terrible and shameful state.

Given the billions of dollars that are allocated to primary and secondary schooling Australia-wide, the basis of the problem must be deeply rooted ideologically and educationally.

The question of racism in the current curriculum must therefore be exposed.

We need an indigenous curriculum that will cater to the needs of aboriginal students and help strengthen their communities.

A progressive curriculum

Indigenous communities around the world have long offered the principles by which they recommend an specialised curriculum should be built.

These principles include learning from the land, beginning from community interest, incorporating community culture, history and language, the centrality of practical experience and the respectful participation of Elders.

This is a democratic curriculum.

Why have non-Indigenous schools and systems found these ideas so difficult if not impossible to implement?

Even a cursory inspection would reveal that principles such as these are very close to those of democratic inquiry learning supported strongly over the past century by progressive educators everywhere.

The contradiction between an inquiry curriculum and what currently exists must be too difficult to contemplate.

Building on knowledge

The Swiss psychologist, Jean Piaget pointed out that children are very active, indeed practical and concrete learners – a concept that may still be misunderstood today.

He suggested that children tinker with their environment and intellectual tools, building on what they know to understand what they do not.

Similar to the findings of the French anthropologist Claude Levi-Strauss, this can be seen as a “science of the concrete”, where children explore the relationship between natural objects and establish a conceptual vocabulary for their own scientific and narrative thinking. When the relationship between the known and the unknown is out of balance, then learning becomes disjointed, confusing and counterproductive.

For Indigenous peoples, connection with the land, trees, rivers and animals is vital for learning and meaning and, if broken, places life itself at risk.

Conversely, if these connections are strengthened then the local environment becomes the springboard for all learning, the construction of explanation and the process of theorising.

This is essential for non-Indigenous children as well.

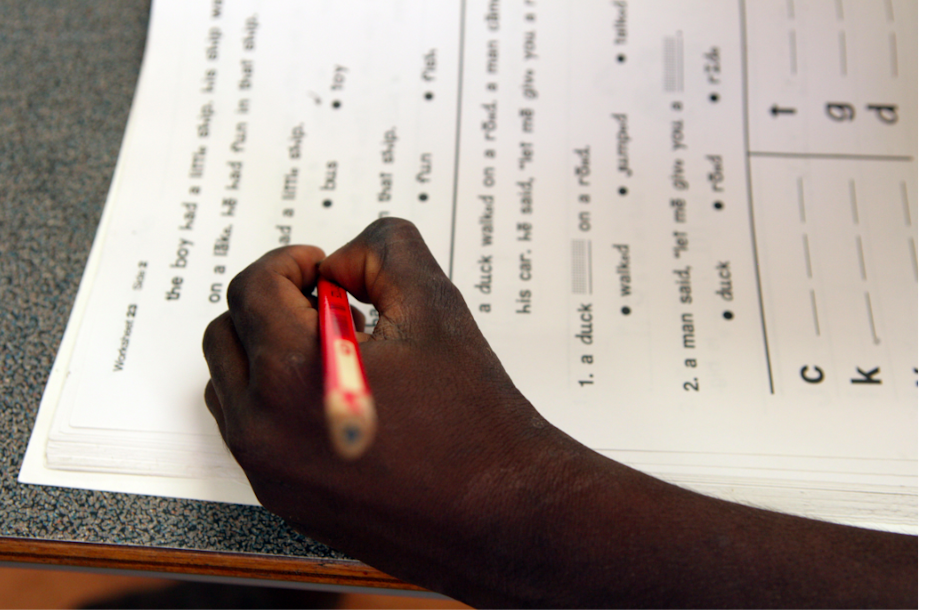

Practical learning

Many schools do not pay enough attention to the concrete and move too quickly to abstract thinking.

Of course, humans have a tendency to use both processes together and cross between them as necessary to solve problems.

But a denial of the experiential too early will result in an inadequate practical base for thinking about cause and effect. Going for a walk by the creek is a good basis for all learning.

In commenting on issues such as these, the American psychiatrist, Jerome Bruner, noted that there are two modes of learning – the scientific and the narrative.

The scientific mode is more empirical, where there is a conscious process of working with the definite properties of objects.

On the other hand, the narrative is more descriptive and communicative, where we proceed more intuitively and informally with the relationship between ourselves and the objects under consideration.

Again, it appears obvious that as young people move to the middle and senior years of schooling, they begin to view knowledge in more abstract and scientific terms, rather than the concrete and narrative.

Child-centred learning

Educators sometimes view this knowledge as having the internal coherence of formal logic. This can be intimidating, when students experience knowledge in uncertain and changing ways.

Based on this argument, the problems faced by Indigenous children in school are problems faced by all children, only more so.

There is an alienation from the knowledge of personal experience, from social identity as a capable learner and the ability to develop local understanding to embrace more global ideas.

These processes need to be incorporated across the curriculum for all children.

What this means is a curriculum that begins with the knowledge and understanding of the child, rather than that of the school.

It means learning that is project-based, where children negotiate the main topics they wish to pursue and where teachers provide a framework of ideas and practices as the work unfolds.

It probably means less subject content and a greater emphasis on discussion and communication of progress between parents, teachers and students.

The curriculum after all is a form of social life.

An inclusive curriculum

There is no reason why the principles of learning supported by Indigenous peoples cannot be incorporated across the curriculum for all children.

There is a remarkable overlap of intent between these principles and those that underpin inquiry learning and which have been acted upon with integrity by progressive educators over the past one hundred years.

To not do so for Indigenous interest is inherently racist.

There may be anxiety from some parents and opposition from some teachers when the implications of a truly democratic and inquiry curriculum are confronted.

It is, however, time for Australia to make this transition, to benefit the learning of all children, Indigenous and non-Indigenous alike.

A curriculum which shamefully and knowingly disadvantages Indigenous children cannot be tolerated any longer.