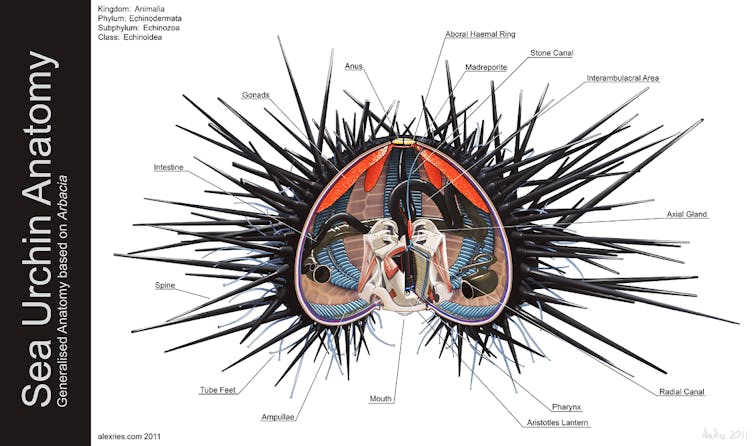

When you open a science textbook or magazine, it’s often the images that capture your attention. Some of these images help you visualise the topics, while others - such as diagrams - can be instrumental in helping us understand difficult concepts.

Creating scientific illustrations can require collaborations between scientists and illustrators. Sometimes they require an illustrator with specific skills or training, such as a natural history or scientific illustrator.

A scientific illustrator is defined as an illustrator who serves science. So assuming that the artist is working with a scientist there shouldn’t be any problems.

But there are.

The process

A scientific illustration could be thought of as operating on three levels:

a simple line diagram that is accurate such as a visual description, a plan or map

an illustration that describes the subject accurately but incorporates specific surface detail such as colour and patterns, etc.

an artwork that could be best described as an illustration based on all of the above but is more about aesthetics than science

Accuracy in terms of shape and related parts is paramount, regardless of the amount of detail, but there are several variations on this. In the case of a beetle, the legs are in the correct scale compared to the body. The amount of surface detail, pattern, body markings and so on can be relatively simple or more complex depending on the type of rendering. Simple black line with shapes to define pattern or stippling to define shapes, tone and form of the subject.

The normal process of drawing a beetle specimen is to look at the fine details of the beetle under a microscope and then start drawing. The details and accuracy are checked with the scientist before the final rendering begins. Care must be taken that artistic license is avoided and the artist sticks to the truth.

The main techniques the artist uses are stippling or cross-hatching and the surface either scraperboard or ink on Bristol board. These techniques and surfaces give the clean delicate lines required for the production of an accurate scientific illustration.

An example of a good scientific illustration of a bird is one that displays detail that is flattened, so that identification is made easy. When standard artistic techniques are used to embellish the bird, it is no longer considered strictly as a good scientific illustration, even though it may be a good artwork.

This is because the shadows, which describe a subject’s form, are not important to identifying the bird species, and thus could be considered a distraction.

The important issues for the scientist are that the illustration or diagram shows all the necessary parts clearly, accurately and to scale, to impart the information they are trying to communicate.

Botanical plates must describe all identifiable parts of the plant, provide a reference of scale and describe illustrated elements in a legend.

The conflicts

The parameter by which an artwork is measured is not always well-defined. What is considered a good illustration can differ between the opinion of a scientist and that of an illustrator.

It seems that what a scientist wants is open to a variety of interpretations.

A few years ago a book on frogs – which I’ll discreetly refuse to name – was brought to my attention. A scientist had written it and the same scientist also did the illustrations. From an artistic point of view the illustrations were considered to be clumsy, almost childish, not very well rendered and quite ugly.

If a student of natural history illustration had produced them they would not have received a good mark for their efforts. But you would assume that the illustrations must have been considered accurate by the scientist and worth publishing.

Although, that fact is not known and assumptions can be dangerous in this area.

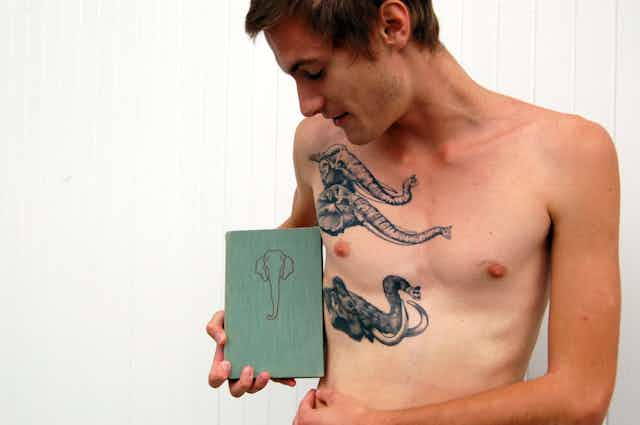

In another example, a student - who was obsessed with illustrating beetles - wanted some constructive feedback from a scientist about the accuracy of her illustrations. I considered the illustrations (see image below) to be a very well executed coloured illustrations of beetles. The student was aware of the parameters required to produce a good illustration.

The feedback she received from the scientist suggested he had little interest. He made a comment on the antennae not being “right” and slipped the artwork back into the student’s folder.

It is obvious that the aesthetics aspect was not of interest to the scientist and he would have been just as happy to have a basic line diagram.

The student was understandably upset and received virtually no feedback. She did not want praise but wanted an indication of what she was doing wrong, or how she could improve her artwork.

I showed the artworks to a published entomologist who happened to be an artist as well and he gave very different and useful feedback. He pointed out the minor faults and admired the beauty of the artworks.

So this raises a couple of obvious questions: to judge what makes a good science illustration properly does someone have to be trained in both areas? Or do the parameters need to be established up front?

Botanical illustrations have some guidelines, but again there are anomalies and the differences appear to depend on who is looking at them and whether the information that has been translated from the specimen had been portrayed accurately and efficiently.

What is good or bad could be – and has been – debated for a very long time. Meanwhile the production of good scientific illustrations will remain as an agreement between individual artists and the scientist they work with.

Perhaps that is how it should be.