Some years ago while researching for my book on suicide in Australia, I thought it would be interesting to begin the book with a case study of the first recorded settler suicide in Australia. It did not take me long to find out this information.

Robert Hughes’s then newly published book The Fatal Shore gave a vivid account of Australia’s first recorded suicide in the following words: “The oldest female convict was Dorothy Handland, a dealer in rags and old clothes who was eighty two years old in 1787. She had drawn seven years for perjury. In 1789, in a fit of befuddled despair, she was to hang herself from a gum tree at Sydney cove, thus becoming Australia’s first recorded suicide”.

It didn’t happen

Search for more information about her life in Australia discovered that contrary to Robert Hughes account, also found in several other well known Australian history books, Dorothy Handland did not hang herself at Sydney Cove in a fit of befuddled despair. In fact she served her seven years at Port Jackson without incident. On 4 June, 1793 she embarked on Kitty for England, and was among those reported on board at Cork on 5 February, 1794.

I also discovered a story about a popular rhyming children’s game of forfeits well known even up to present day in England, “Here Comes an Old Woman from Botany Bay, What have you got to give her today”, in an Australian history journal which suggested that she might have been the subject of this game rhyme.

But I found no record of Dorothy Handland’s life in Australia and that has puzzled me ever since. Let me offer a plausible explanation as to why Dorothy Handland found noone interested in her seven year ordeal in Australia.

From the very onset, convict women had three possible roles open to them: whore, indentured worker, wife/mistress or a combination of these. The construction of these roles began almost from the very beginning ships of the First Fleet started their voyages. Women were seen as whores. According to officer in command of the expedition convict women threw themselves at the sailors and Royal Marines in “promiscuous intercourse” and “their desire to be with the men was so uncontrollable that neither shame nor punishment could deter them”.

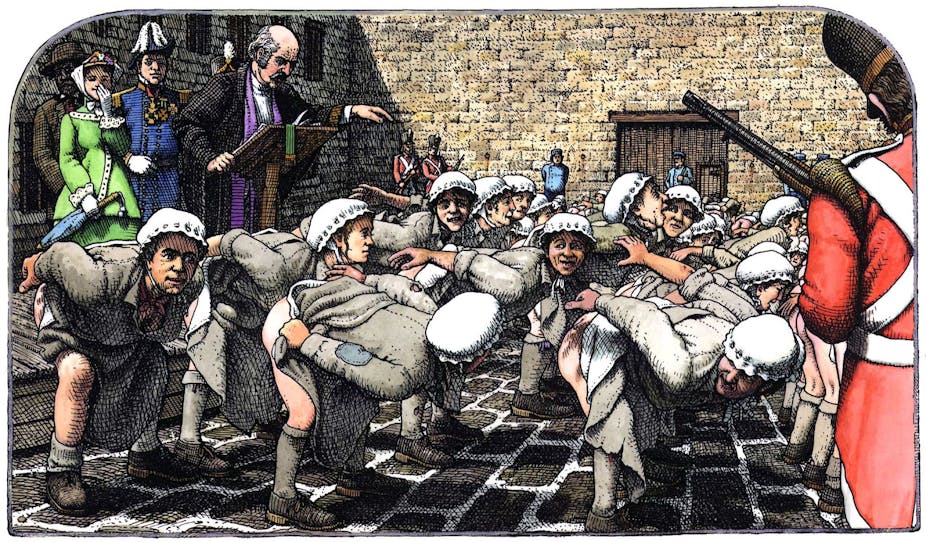

According to Robert Hughes, on arrival at Botany Bay “the women floundered to and fro, draggled as muddy chickens under a pump, pursued by male convicts intent on raping them… the sailors on Lady Penrhyn applied to her master, Captain William Sever, for an extra ration of rum to make merry with upon the women quitting the ships. Out came the pannikins, down went the rum, and before long the drunken tars went off to join the convicts in pursuits of the women… It was the first bush party in Australia with some swearing, others quarrelling, others singing… as the couples rutted between the rocks, their cloths slimy with red clay, the sexual history of colonial Australia may fairly be said to have begun”.

A man’s country

The conditions, as they were at the beginning of the new colony, were conducive to making women convicts as sex objects for men: convicts, marines and officers. Besides giving or receiving sexual favours women had to work as labourers and servants for the officers under back breaking and harsh conditions. A lucky few managed to establish families, mainly with fellow convicts.

Of the people transported to the antipodes between 1788 and 1852, about 24,000 were women: one in seven. Many Australians still think their Founding Mothers were whores. Undoubtedly some were prostitutes and some became prostitutes to survive by selling their sexual services. What is quite certain, however, that no women were actually transported for whoring, because it was never a transportable offence.

The vast majority of female convicts - more than 80% - were convicted of petty theft. The crime of violence appeared very low among them. And yet there was rarely a comment on colonial society, scarcely a passage of evidence to various Committees of the government, hardly a tract or a diary or a letter home, that missed the chance to describe the degeneracy, incorrigibility and worthlessness of women convicts in Australia. Military officers believed this and so did doctors, judges, parsons, governors and, of course their respectable wives.

Convict men might in the end redeem themselves through work and penance, but women almost never. It was as though women convicts had passed the ordinary bounds of class and become a fiction, nor for pornography: crude raucous Eve, suckling rum and mothering bastards in the exterior darkness, inviting contempt rather than pity from the social superiors, rape rather than help from men.

Australian historians generally swallowed this stereotype. Some later Australian feminist historians have striven to retain the picture while dismantling the biases, arguing that that their fate was foisted on them by a tyrannous male power structure which deemed it necessary to have supply of whores to keep the men, both convict and free, quiescent. Under such conditions an old women like Dorothy Handland could not fit into a whore, worker or wife roles.

No place for those who don’t fit the mould

She was in other words superfluous to the requirements of the time and thus attracted no attention and labours of her seven long years were invisible to her fellow convicts, their masters and obviously to many, if not all, historians.

To give history of the founding of Australia a touch of authenticity the makers of history and those who recorded it found it convenient to assign Dorothy Handland a place in it by claiming that her age, diminished mental and physical abilities and the harsh conditions of the alien land totally befuddled her and she found an escape, an exit, by hanging herself.

But she lived, worked and survived seven years in merciless physical and human conditions of the new colony and returned to her homeland. She may not have left a mark on Australian history but Dorothy Handland offers an extraordinary example of the triumph of human spirit over adversity.