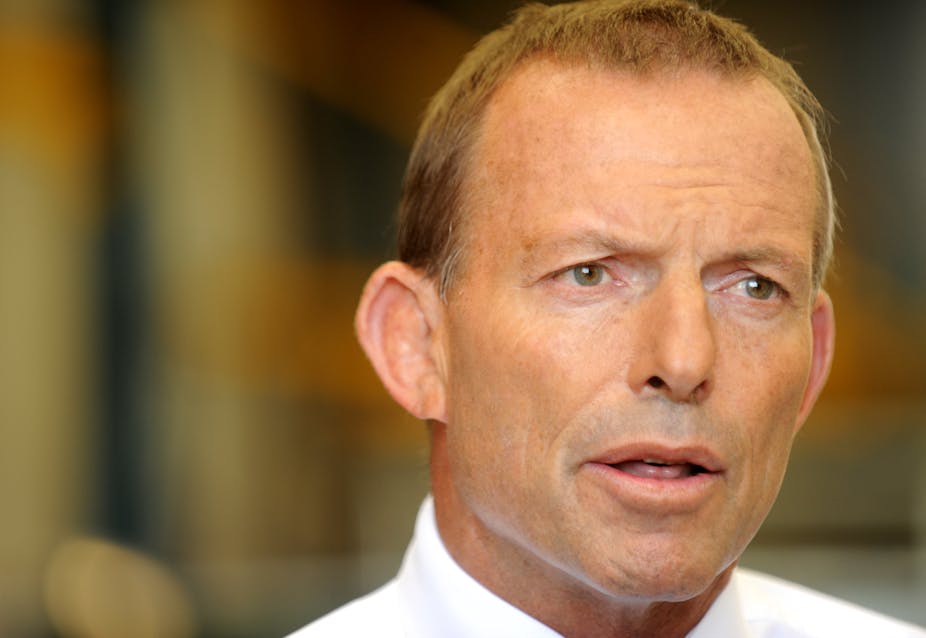

Opposition leader Tony Abbott has said that under a coalition government every boat coming to Australia carrying asylum seekers will be sent back to Indonesia.

The Indonesian police, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees and former chief of the defence force Admiral Chris Barrie have all expressed concern the policy breaches international law, and could risk lives at sea.

Julia Gillard has called the promise “reckless”.

The Conversation spoke with Monash University legal expert, Maria O'Sullivan about the legal implication’s of Abbott’s policy.

What are the legal consequences of the Coalition’s policy of “turning back” boats?

There’s a difference here between International Maritime Law, the Law of the Sea and International Refugee and Human Rights Law. Which law applies depends on the status of the persons concerned. Are they claiming asylum or are they ordinary migrants?

If you have something like a whaling vessel, the issue is clearer - Australia can turn a ship back because our territorial waters is part of our territory. So in some cases we can legally push a vessel back.

However, the issue is more complicated when dealing with asylum seekers. Under International Maritime Law, we have a duty to rescue vessels at sea and of course, asylum seeker boats are usually in distress because they are typically not seaworthy.

What about under international refugee law?

Australia also has obligations under international refugee law, which applies to both asylum seekers and refugees. There is an important difference between asylum seekers and refugees, because someone seeking asylum does have a right to have that claim heard. This does not mean that they have a right to receive that asylum, but they do have a right to ask for it.

If Australia exercises jurisdiction over a vessel, by, for instance, physically going on board as we did during the [Tampa affair] and take control of it, then under international law we exercise our jurisdiction over that vessel and certain obligations arise from that.

Australia cannot directly return the vessel to, say, Afghanistan if there are asylum seekers that are on board saying that they’re from Afghanistan. This is because Article 33 of the 1951 Refugee Convention prohibits “non-refoulement”. This means Australia cannot return a refugee to a territory where they would be under threat to their life or freedom for reasons of political opinion, race and so on.

This means that we cannot return them either to Afghanistan directly, but it also means we cannot return them to a country where they would then be sent (by that country) back to Afghanistan. For example, if there was a high chance that Indonesia would be sending asylum seekers back to their country of origin, then Australia cannot push those asylum seekers back to Indonesia.

The issue of refoulement is quite complicated. Article 33 of the Refugee Convention prohibits expulsion or “return” of refugees. The word “return” has been interpreted by many to apply even when the asylum seekers do not reach Australian territory - that is, people don’t have to come into Australia in order for that obligation to operate.

Now the US state department in a number of cases a few years ago argued that the non-refoulement obligation doesn’t arise when the asylum seekers are in international waters. In a famous US Supreme Court case of Sale v Haitian Council the Court actually held that if the push back occurs on the high seas then it’s okay, because the vessel hasn’t actually entered the country’s jurisdiction. However, UNHCR and many academics have been critical of that US judgement.

So this issue is complicated, it involves the interplay between maritime and refugee law, the concept of “jurisdiction” and the obligation not to return. Does that extend to just Afghanistan or Iraq, or does it extend to Indonesia? What if conditions are so bad in Indonesia that asylum seekers feel they have to return back to their country of origin?

Does Indonesia have the legal right to refuse the boats when they come back?

If they contain Indonesian citizens they have to accept them, but if they’re asylum seekers, there’s actually no legal right. As Indonesia is not a party to the Refugee Convention, they currently have no legal obligation to accept asylum seekers. Indeed, even parties to the Refugee Convention like Australia did refuse the entry of asylum seekers during the Tampa affair in 2001.

The problem is that this situation could theoretically start “people ping pong”, where we take the boats back to Indonesian territorial waters and Indonesia says no, we don’t want them. In that situation Australia would eventually have to accept them. But there could be a situation where people are just being dragged from country to country.

What are Australia’s legal obligations when a boat is in trouble, or not seaworthy?

Basically under the International Convention on Law of the Sea, the country exercising jurisdiction attempting the return of the boat has to ensure first that the boat is seaworthy, and second that the people are in good condition, they have food and water, so that they are able to survive the journey back to a country like Indonesia.

And then if the boat is not seaworthy, if it’s in distress, the Australian authorities would have an obligation under the International Law of the Sea to rescue that vessel. Importantly there’s also an obligation to then take those people and allow them to disembark at a place of safety and this really, to my knowledge, hasn’t been analysed very much. What do we mean by a “place of safety”? Would it mean, if they’re not seaworthy, we could take them back to Indonesia, or would that mean bringing them back to Australia?

I haven’t seen much written on this aspect, but that’s primarily because most countries do accept asylum seekers, they may reject their claim but they do actually accept them into their territory for processing.

Would this asylum seeker policy affect Australia’s relationship with Indonesia?

Definitely. There were news reports about how unhappy Indonesia was with the Malaysian solution and trying to get a regional burden-sharing arrangement. Because Indonesia feels that we actually don’t carry the fair burden of asylum seeker policy in the region.

That tension is not a new thing, during the Tampa affair this happened as well. The [Indonesian] foreign minister said it was a case of “megaphone diplomacy”. I think there is a perception in the whole region that we are a wealthy, Western country which is well-resourced and underpopulated, yet we’re trying to get them to shoulder all the burden of asylum seekers. The question asked is, if we’ve got the resources, why aren’t we taking the fair burden of the asylum seeker issue in the region?

I think that tension will be exacerbated if we were to pursue push-backs in the region.