Tobacco, says the World Health Organisation (WHO), is “the only legal consumer product that kills when used exactly as intended by the manufacturer.”

Supporting the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, the Australian Parliament has passed The Tobacco Plain Packaging Act 2011 (Cth). The legislation was supported by all the major parties.

Labor Attorney-General, Nicola Roxon, argued, “Plain packaging means that the glamour is gone from smoking and cigarettes are now exposed for what they are: killer products that destroy thousands of Australian families.”

The leader of the Coalition Opposition, Tony Abbott, acknowledged: “This is an important health measure. It’s important to get smoking rates down further.” The Greens also supported the measure - and called for the Future Fund to end its tobacco investments.

In response, Japan Tobacco International and British American Tobacco brought legal action against the government in the High Court of Australia, claiming that the Act amounts to an acquisition of property on less than just terms under the Australian Constitution. Phillip Morris Ltd and Imperial Tobacco joined the case, and supported their fellow tobacco companies.

In its defence, the Commonwealth was supported by the governments of the Australian Capital Territory, the Northern Territory, and Queensland. The Cancer Council Australia made written submissions, but was not given leave to intervene.

The High Court of Australia heard arguments over three days from the April 17 to 19, 2012. The various parties enlisted battalions of lawyers, the proceedings received intense media attention, and the public galleries were packed. Here’s how it went.

Big Tobacco’s arguments

Tobacco companies struggled with their argument that the introduction of the plain packaging of tobacco products amounted to an acquisition of property on less than just terms.

There was much discussion as to whether the Commonwealth had indeed effected an “acquisition” of the tobacco trade marks. Japan Tobacco International’s barrister argued, “The Commonwealth law by its terms abrogates the power to substitute any message the Commonwealth chooses on what we say is our billboard.”

The tobacco companies argued for a broad view of property under the Australian Constitution, and claimed to hold various forms of intellectual property in relation to tobacco packaging, including trade marks, patents, designs, copyright and passing-off.

Their barristers said the intellectual property rights of tobacco companies had been extinguished, or at least severely impaired. One said, “On our analysis, everything has been taken.”

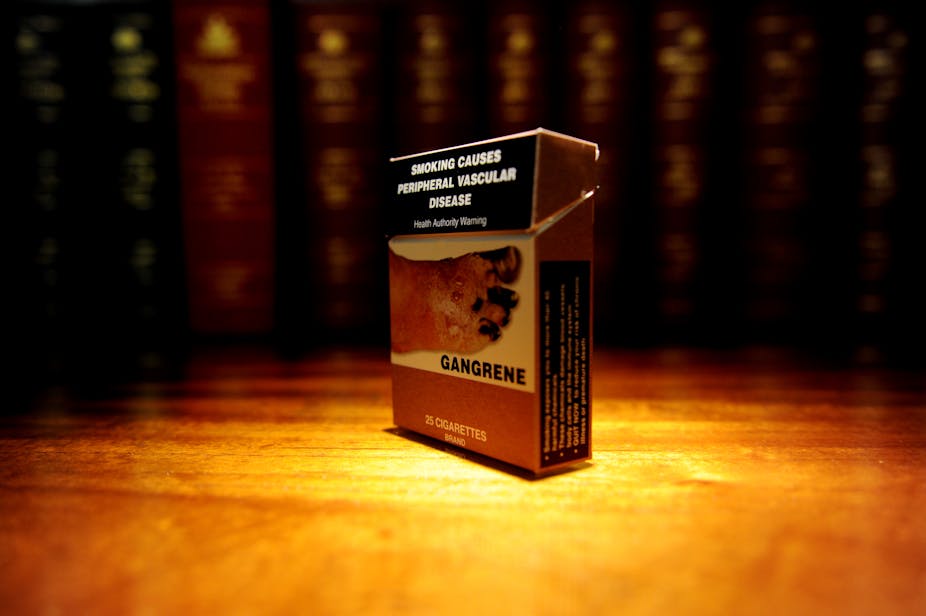

There was much debate about the semiotics of tobacco packaging and clear festishization of the tobacco pack. The judges were invited to closely inspect the packaging of tobacco products. And there was a discussion of the use of words, colours, emblems, badges, and logos - with references to examples such as Camel cigarettes.

But the judges questioned the analogies drawn between property cases, dealing with land, and intellectual property cases on the acquisition of property. Justice Gummow asked, “Are any of these cases about intangibles? A lot of the American cases are about land, are they not?” It was surprising that there was relatively little discussion about past Australian precedents on intellectual property and constitutional law, such as the Grain Pool case, the Blank Tapes case, the Nintendo case, and the recent Phonographic ruling.

Tobacco companies wanted to draw a distinction between graphic health warnings and “excessive regulation” (plain packaging). Justice Kiefel responded, “The degree of regulation may be extremely restrictive and yet there be no acquisition.”

British American Tobacco argued tobacco companies should receive compensation for public health advertisements. “The fact that it is an improving message or a good message may be socially desirable and if it is then the Commonwealth should pay for it,” they argued.

As a witness to the proceedings and an expert in intellectual property, the arguments of the tobacco companies about acquisition of property often seemed synthetic and unreal to me.

The Commonwealth

The Commonwealth government mounted a strong defence of the legality and constitutionality of the plain packaging of tobacco products. Their submissions explained the measures were “directed to informing, redressing and reducing harm to the public health that is caused by use of the tobacco products.”

The solicitor-general for the Commonwealth, Stephen Gageler, argued the law was “no different in principle from any other specification of a product standard or an information standard for products or, indeed, services that are to become the subject of trade in the future.”

He observed, “The product information required to be placed on these products differs only in intensity from product information that is routinely mandated to accompany therapeutic goods, industrial chemicals, poisons and other products injurious to the public health”. He commented, “The mandatory graphic health warnings are the skull and crossbones for a digital age, nothing more.”

The Solicitor-General said that “to suggest that the tobacco packages become little billboards for government advertising is wrong.” He denied the government was engaged in advertising, or derived any such benefit, and contended that a regulatory norm of conduct was not an acquisition of property.

The government stressed the sale and packaging of cigarettes had long been regulated in Australia, and that plain packaging was but the latest step in this process.

The solicitor-general argued the statutory rights of intellectual property are often varied and modified, adding a trademark “must at least be subject to a subsequent prohibition on use to prevent harm to the public or to public health”. Indeed, Article 8 of the TRIPS Agreement 1994 recognises that “members may, in formulating or amending their laws and regulations, adopt measures necessary to protect public health and nutrition”.

Solicitor-general also argued that the concept of just terms raised larger questions of fairness and justice under the constitution.

The Commonwealth maintained that it would be incongruous to compensate Big Tobacco, “For the Australian nation representing the Australian community to be required to compensate tobacco companies for the loss resulting from no longer being able to continue in the harmful use of their property goes beyond the requirements of any reasonable notion of fairness.”

Sideshows: margarine, boxes and Ratsak

Notwithstanding its serious subject matter, the case also had its colourful moments.

An amusing esoteric sideshow in the case was the fierce battle between junior lawyers over legal history relevant to the case. There was discussion of the Margarine Act of 1887 (United Kingdom), which required the plain packaging of margarine and margarine-cheese. But there were no reports of 19th century margarine and margarine-cheese makers ever ran litigation over plain packaging.

There has been much debate about absurd patent applications of late. And in this case, British American Tobacco revealed that it has filed patent applications for packages for tobacco products. Here’s the WIPO version of British American Tobacco’s suspect patent application for a “soft cup package for tobacco products”.

What is novel, inventive or useful about a soft cup package for tobacco products? Patent law should be encouraging the progress of science and the useful arts - treatments and therapies for cancer, for instance - rather than cigarette boxes.

Another oddity was the frequent comparisons between warnings on Ratsak poison, and health warnings on tobacco products, which gave the case a peculiar ending. The barrister for Japan Tobacco International invited the seven judges of the High Court of Australia to inspect the labelling on Ratsak, which he had bought at local shops.

A brilliant Australian idea

The High Court of Australia has reserved its decision. A ruling can be expected later in the year.

French CJ signalled that he thought that the matter of tobacco was exceptional. “None of these cases… involve somebody putting into the marketplace a substance which places at risk of serious and fatal disease. We are talking about something in quite a different category, are we not?” he asked.

The case provides the court with an opportunity to contemplate the constitutional role of the Commonwealth in regulating and protection health.

In terms of larger principles, the High Court of Australia can provide guidance on:

the difference between acquisition of property and regulation;

the relationship between property and intellectual property; and

the standard of justice underlying just terms.

It remains to be seen whether the ruling will have larger implications for the labelling of therapeutic goods, food, alcohol, and beverages, such as soft drinks.

What we know for certain is that, far from heralding the end of the fight about plain packaging, this case is merely one battle in an ongoing war for better public health.

But it will certainly have wider international implications. Geoffrey Robertson QChas predicted that, not only will the Commonwealth win the case, but other countries will follow the “brilliant Australian idea”. Both New Zealand and England have initiated public consultation processes, with a view to establishing schemes for the plain packaging of tobacco products.

Meanwhile, other attempts by tobacco companies to thwart this measure will continue. Big Tobacco will no doubt seek to challenge plain packaging in a wide array of arenas. The Ukraine, for instance, is leading a misconceived challenge to Australia’s plain packaging of tobacco products under the TRIPS Agreement 1994. And, there’s a contrived action against Australia’s scheme under an investment treaty between Hong Kong and Australia.

Health activists are also concerned about Big Tobacco’s involvement in the development of free trade agreements, such as the Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement and the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement. There are fears that such treaties will include parts aimed at undermining tobacco control measures.

Coda

British American Tobacco Australasia Limited v. The Commonwealth of Australia Case S389/2411

JT International SA v. The Commonwealth of Australia Case S409/2011

Transcript of Day 1 of oral argument