The debate about alcohol’s harms is seemingly endless: the role of alcohol in violence, unplanned sex, injury and motor vehicle accidents, the teen binge-drinking epidemic, the risks of cancer and liver disease from chronic alcohol use and raising the legal age for purchase have all been discussed. Notably absent from the discussion is the effect of alcohol on the unborn child.

Foetal exposure to alcohol can have devastating consequences, impairing the subsequent growth, neurodevelopment, learning, and quality of life for the child.

Alcohol is toxic to the foetal brain

Alcohol is a teratogen, or toxin, that readily crosses the placenta. When a pregnant woman drinks, the foetus is bathed by blood containing alcohol, which can disrupt development of the brain, internal organs and face.

Foetal alcohol spectrum disorders encompasses a range of disorders that may result from alcohol exposure in the womb, including foetal alcohol syndrome, neurodevelopmental disorder associated with alcohol exposure, and a range of alcohol-related birth defects.

In north America, foetal alcohol spectrum disorders are the most common cause of developmental delay and are said to affect between 2% and 7% of all births.

Children with foetal alcohol spectrum disorders have variable clinical features. They may have a small or structurally abnormal brain, but even in the absence of such changes, they may have significant abnormalities of function, including problems with learning that limit their academic achievement. Ultimately, this affects their capacity for employment and independent living.

Although the IQ range for such children is wide, they have particular problems with memory, executive function (planning and conduct of complex tasks), and numeracy. They often require remedial education, and frequently exhibit difficult behaviours (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, conduct and oppositional disorders, risk-taking, anxiety and depression). They may have either solitary or overly-friendly personalities.

These children may grow poorly and have defects, and hence abnormal function, of the heart, kidneys, ears, eyes and other organs. These problems don’t go away.

Foetal alcohol spectrum disorders are lifelong and as children enter adolescence, they are at higher risk than the general population of drug and alcohol dependence, anti-social and inappropriate sexual behaviours, mental health disorders, trouble with the law and incarceration.

But these disorders are preventable.

Safe drinking and pregnancy

People frequently ask how much alcohol is safe during pregnancy. Of course, this can never be answered based in human studies, and I think that it may, in fact, be irrelevant.

We know that women who drink no alcohol during pregnancy pose no risk to their foetus. And we know that frequent, high intake, particularly binge drinking, increases the risk. We also know that birth defects may result from first trimester alcohol exposure but that the brain is vulnerable to damage throughout the pregnancy.

And we know that risk to an individual pregnancy is impossible to predict because maternal (and hence foetal) blood alcohol levels are influenced by a range of factors including age, body composition, genetics and prior disease. So it’s better to apply the precautionary principle as recommended in Australia’s national alcohol guidelines – “for women who are pregnant or planning a pregnancy, not drinking alcohol is the safest option.”

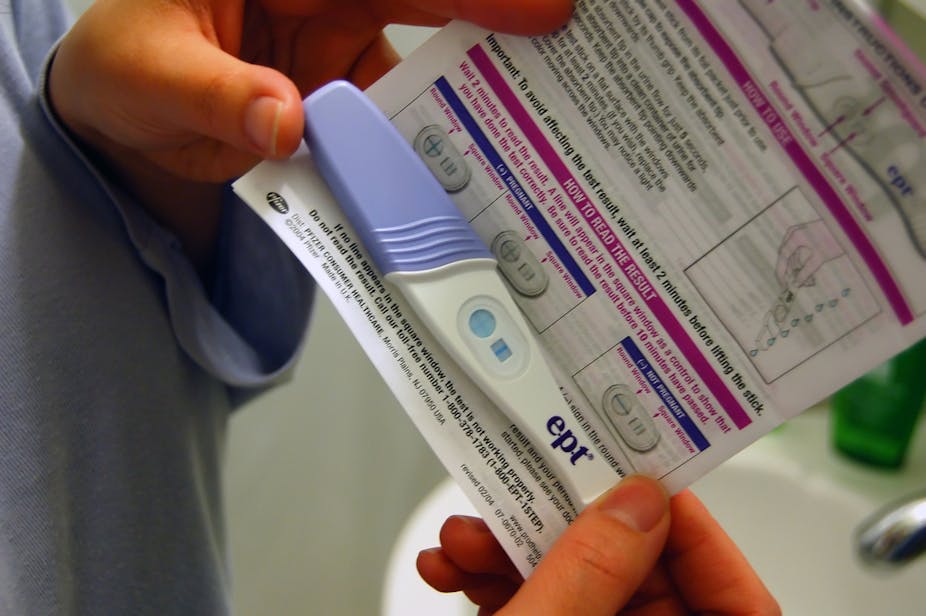

Adding to this complexity is the high rate of unplanned pregnancy, estimated at around 50%, which suggests that inadvertent alcohol exposure may be common.

Prevention is the only option

Strategies to address foetal alcohol spectrum disorder have to focus on prevention. We need highlight the potential harms of alcohol use in pregnancy, as many women and their partners just don’t know about it. This will involve public education strategies, including labelling of alcoholic beverages.

But labelling will only effectively improve knowledge if mandated and enforced, not left to the alcohol industry. Labels must be legible, prominent, and informative.

A recent survey by the Foundation for Alcohol Research and Education (FARE) has showed that, under the current voluntary code, only 16% of alcoholic beverages were labelled and many of these were unreadable or simply referred to a website.

And this brings me back to the debate about alcohol raging in our community. Preventing foetal alcohol spectrum disorder, like all other alcohol-related harms, requires attitudinal and behavioural change. Prohibition is not the solution and behavioural change must be supported by interventions with proven efficacy.

This is the eighth part of our series looking at alcohol and the drinking culture in Australia. Click on the links below to read the other articles:

Part One: A brief history of alcohol consumption in Australia

Part Two: Social acceptance of alcohol allows us to ignore its harms

Part Three: My drinking, your problem: alcohol hurts non-drinkers too

Part Four: Alcohol-fuelled violence on the rise despite falling consumption

Part Five: ‘As a matter of fact, I’ve got it now’: alcohol advertising and sport

Part Six: Advertising’s role in how young people interact with alcohol

Part Seven: Big Alcohol and Big Tobacco – boozem buddies?

Part Nine: ‘Valuable label real estate’ and alcohol warning labels

Part Ten: Forbidden fruit: are children tricked into wanting alcohol?