Welcome to the Future of Work, a series from The Conversation that looks at the ongoing evolution of the workplace. Today, London Metropolitan University’s Frances Holliss looks at the growth of home-based work and the implications for urban design.

The home-based workforce is growing rapidly, globally. This is a popular, family-friendly, environmentally-sustainable practice; good for both the city and the economy. But we do not generally design for it at either an urban or a building scale.

This needs to change.

As ubiquitous as the “house”, the building type that combines dwelling and workplace has existed for hundreds - even thousands - of years. Examples can be found worldwide.

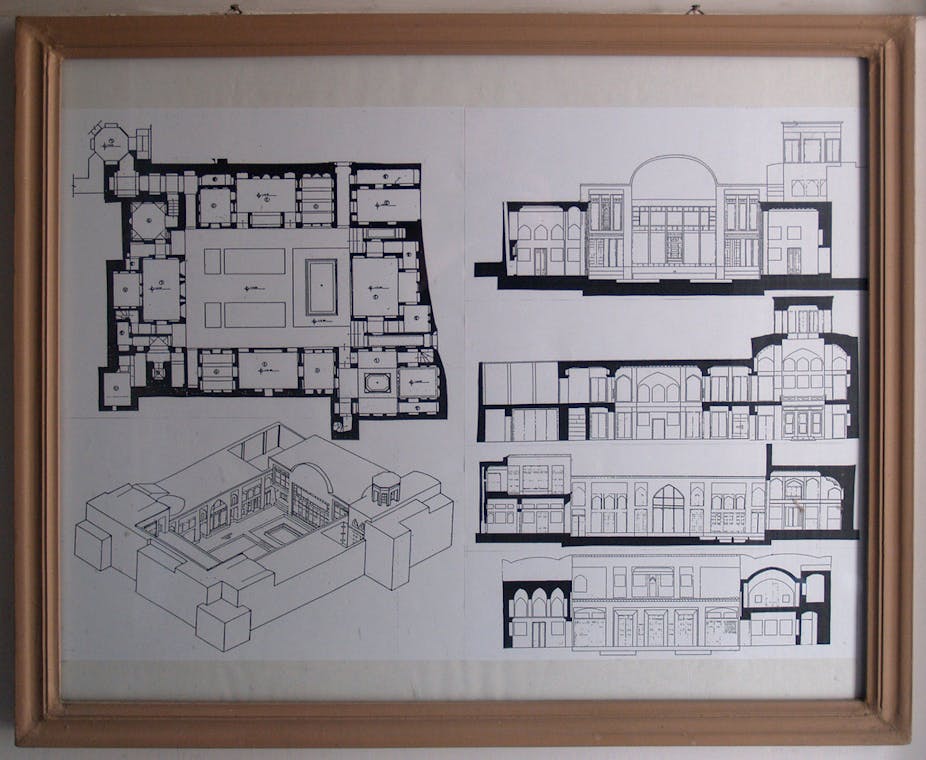

They range from the Japanese machiya to Malaysian shop-house; Iranian courtyard house to Vietnamese tube house; medieval English longhouse to contemporary live/work unit. Taking different forms according to culture and climate, these buildings are often so familiar that we do not notice them.

Their history has not been constructed before. But it can be found - fragmented and often disguised - in publications about houses or workplaces, about individual buildings or architects’ oeuvres, or about particular geographical locations or historical periods of history.

The “workhome”

Carl Linnaeus, the 18th century botanist whose classification system for the biological sciences is still in use today, said: “If you do not know the name of things, the knowledge of them is lost too.”

This may be key to understanding why so little is know about this age-old building type.

Before the industrial revolution, it was called “house”, with sub-sets of bake-house, bath-house, ale-house and so on. But through the 20th century, the term “house” came to refer to a building type in which people cook, eat, bathe, sleep and watch TV, and nothing else. So the building that combines dwelling and workplace lost its name.

In order to be able to gather knowledge about it, this building type needs a name. So I have coined the generic term “workhome” to refer to all buildings that combine dwelling and workplace.

Research process

To establish the existence of the workhome, I excavated its history from medieval times to the present day in England.

Then, building on work carried out by North American architects Penny Gurstein and Thomas Dolan, I set out to identify some (ideally universal) design “truths” for workhomes.

A close scrutiny was made of the lives and premises of 76 contemporary home-based workers in urban, suburban and rural contexts in England. Participants were selected from across the social spectrum, working in a wide range of occupations and inhabiting all sorts of different buildings.

A semi-structured interview was held with each person. Some lasted only twenty minutes while others talked for hours. Many said how much they enjoyed the process and how it affirmed their chosen lifestyle.

Photographs were taken of each building, inside and out, except where these would endanger the inhabitant in some way. And each building was measured so simple plans could be drawn.

Who are these home-based workers?

An analysis of all the home-based workers, first, revealed eight different workhome user-groups.

juggling parents

backbone of the community

professionals

24/7 artists

top-up

craft-worker

live-in

start-up

The analysis highlighted the different spatial and environmental requirements for each group, which hints at the need to revolutionise design for home-based work.

What are these buildings like?

An analysis of the buildings, in terms of their dominant function, found two basic types

home-dominated

work-dominated

Home-based workers either work in their homes or live at their workplaces. A lack of understanding of this basic distinction has led to confusion on both sides of the ocean as local authorities tried to legislate the “live/work” movement.

Three degrees of spatial separation

Most contemporary home-based workers inhabit buildings that have not been designed for the dual use. This often causes frustration, stress and inefficiency. A central issue is the relationship between the “dwelling” and “workplace” elements of the workhome.

Three basic degrees of spatial separation between the two functions were found in the 76 buildings studied. Each is suited to different sorts of home-based worker.

no separation: live-with

some separation: live-adjacent

more separation: live-nearby

The first type combines dwelling and workplace in a single fire compartment with a single entrance. Many different possible models exist, including the “double-height space and mezzanine” and the “workspace in the spare bedroom”.

The second type combines dwelling and workplace in two adjacent fire compartments each with its own entrance. This type is popular in workhomes such as shops, pubs and funeral parlours, where the work involves interactions with members of the public.

The third type separates dwelling and workplace into two buildings a small distance from each other. Each has its own entrance. Common models include the “shed at the bottom of the garden” and the “mews workspace at the bottom of the garden across a courtyard, with a separate access road”.

Design as a tool

Common disadvantages to home-based work include problems with occupational identity and social isolation. The fact that most home-based workers inhabit cities and buildings designed around the dominant spatiality of the industrial revolution, which separated dwelling from workplace, exacerbates this.

Cities and buildings designed around home-based work would inevitably take a different form. It’s time for us to explore this. Recognising the existence of the workhome - and its immense contemporary relevance - is a necessary first step.