Murder is the most serious of all violent crimes, and needs a determined criminal justice response. If there are circumstances in which a killing might be seen as wholly or partly excusable, then this is of interest to all citizens - particularly if these circumstances weigh unevenly against a specific social group.

Provocation is a defence that signals reduced culpability for an intentional killing by replacing a murder conviction with one of manslaughter. Historically it differentiated killings worthy of the death penalty from less heinous killings committed “in the heat of passion” without premeditation.

This was linked to a tradition of male social honour, a breach of which tended to provoke an angry response. Behaviour seen by criminal courts in the past as an affront to male honour included insults arising from drunken fights or a wife’s adultery. Unfortunately, the latter situation is still seen by some, such as Christian lobby group FamilyVoice Australia, to be an acceptable defence to murder today. The perpetuation of such views is partly the reason why provocation has been subject to so much criticism and why some jurisdictions have abolished provocation.

An affront to male honour which in recent decades has been used to argue a case of provocation is the so-called “homosexual advance defence” (HAD), sometimes incorrectly referred to as the “gay panic” defence (which is actually a failed US version of the defence strategy).

Since the 1990s, gay and lesbian activists have expressed serious concerns about homicide cases in which an accused male killer or killers pleads provocation on the basis of an alleged unwanted sexual advance from the victim who was known or assumed to be homosexual.

The argument is that a man who is the subject of an unwanted sexual pass by another man finds this so provoking that he loses self-control and kills. According to the law, if an “ordinary” person could have reacted the way that the offender did by losing their self-control in the face of victim’s behaviour, then the charge of murder will be reduced to manslaughter.

This strategy relies on negative courtroom depictions of the homosexual victim. The logic is that the perpetrator is a “regular” masculine man or youth whose goodwill is pushed to the limit by being propositioned or even sexually touched by a homosexual “nuisance”.

The use of this defence strategy in the NSW case of Green v The Queen in the 1990s reached all the way to the most senior judges in the land. A majority ruling by the Australian High Court favourably viewed the accused killer’s appeal against a murder conviction and paved the way for his eventual securing of a much lighter sentence for manslaughter.

The Green case was subject to much criticism because the court allowed claims of a homosexual advance to substantiate a claim of provocation. In reaching this decision the majority of these judges did not take the opportunity to rule that no ordinary person could be provoked to kill by a non-violent sexual pass. In fact, several comments were made which suggested that such extreme violence may often be expected.

The High Court result in Green mobilised gay and lesbian lobbyists nationwide. It spurred an official Attorney-General’s Working Party Inquiry in NSW which in 1998 recommended that a non-violent sexual advance should be barred from forming the basis of a provocation defence. Nothing came of those recommendations.

More general feminist opposition to provocation because of the way in which it has traditionally privileged male violence and not worked for females has to an extent been more successful and led to provocation being abolished in Victoria, Tasmania and Western Australia.

Other jurisdictions have retained the defence of provocation but amended it with the aim of removing its more problematic aspects. For example, amendments in the ACT and Northern Territory bar the use of provocation on the basis of a non-violent sexual advance. Queensland also retains provocation but bars the defence of provocation in response to the ending or changing of a domestic relationship. Parallel to this reduction in the scope of provocation Queensland has also introduced a specific defence of killing for preservation in an abusive domestic relationship.

The result of these changes is that NSW and Queensland are the only jurisdictions that still retain provocation and have no legislative bar against provocation claims based on a sexual advance (in South Australia provocation is a common law defence and is not found in statute). Two recent cases in Queensland in which provocation was used successfully to reduce charges from murder to manslaughter have once again ignited concern about allowing the defence on the basis of sexual advance.

The ensuing campaign for change led to the creation of a working party in 2011 to examine the operation of the homosexual advance defence and a government pledge to amend the Queensland Criminal Code to, in the words of the former Attorney-General Paul Lucas:

make it crystal clear that someone making a pass at someone is not grounds for a partial defence and by no means an excuse for horribly violent acts.

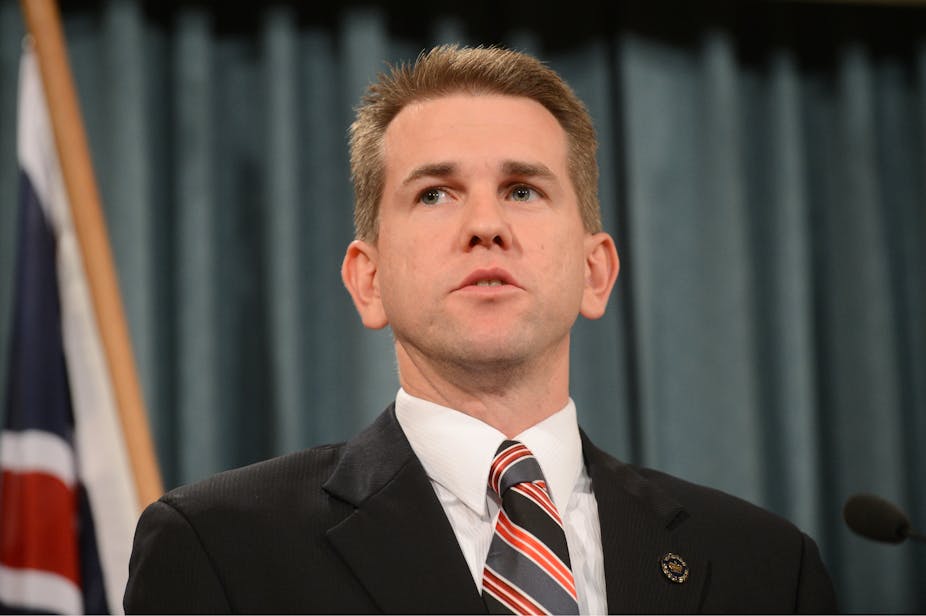

But a change in government means there is now no commitment for reform in Queensland, as stated by the current Attorney-General, Jarrod Bleijie.

Meanwhile, things might be about to change in NSW. In the fifteen years since the Attorney-General’s Working Party recommended changes to the law, successive governments have reneged on their promises of reform or ignored this issue. Now, however, a select committee has been established to inquire into provocation in NSW, and is currently accepting submissions.

This review was sparked by the case of Chamanjot Singh, who was sentenced to six years imprisonment after being found guilty of manslaughter rather than murder of his wife on the basis that he had been provoked by verbal abuse.

It remains to be seen whether NSW will join Tasmania, Victoria and Western Australia in abolishing provocation outright, or whether it will make amendments to remove more controversial elements such as its use in HAD claims.

What sort of signals about male interaction and violence does the legal status of the homosexual advance defence send to men and boys? If the answer to this question suggests physical and even fatal violence as the acceptable response, rather than a simple declaration of non-interest, then we should consider why our society would not tolerate a similar violent reaction from women who are subjected to routine unwanted overtures from men.

The ongoing failure to scrap the homosexual advance defence and the partial excuse it provides to certain forms of male violence is an embarrassment and an injustice for the citizens of Queensland and NSW.

The politicians of NSW now have the chance to change this and we should all hope they do not fail a second time.