The moon. Our nearest neighbour. The main source of the ocean’s tides, and a beacon that drives the lives of animals across the globe. And also, to date, the only object beyond Earth on which humans have set foot.

Over the years, the moon has played a central role in the burgeoning understanding of our place in the universe. Yet despite its proximity to Earth, and the detail with which it has been studied, many of the moon’s secrets still elude us.

In this, and another four articles, I’ll introduce you to some of the ways in which the moon has influenced life on Earth, how it has taught us about the formation of the solar system, and the past (and future) of our exploration of the solar system’s strangest satellite. But first, some initial thoughts on our weird neighbour.

The moon: the stats

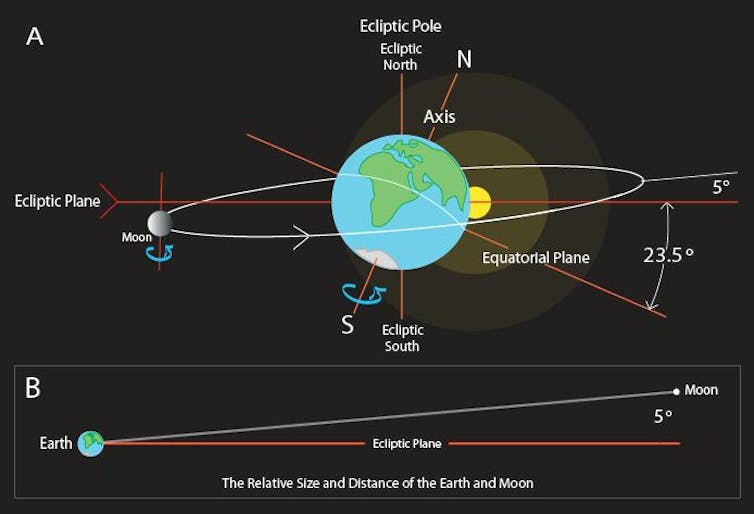

The moon orbits Earth at a mean distance of just over 384,000km. Its orbit is inclined to the plane of Earth’s orbit around the sun by just over five degrees.

If we were looking at the Earth-moon system from beyond Earth’s orbit, we would see the moon spends roughly half its time below the plane of Earth’s orbit around the sun, and the other half above that plane.

The location in its orbit at which the moon passes from below the plane of Earth’s orbit to above that plane is known as the “ascending node”. Over a period of around 18-and-a-half years, the location of the ascending node precesses around the moon’s orbit completely.

Because the rotation axis of Earth is tilted with respect to the plane of its orbit by 23-and-a-half degrees (the cause of the seasons), the moon’s orbital tilt, with respect to the Earth’s equator, varies over this 18-and-a-half year period between about 18 and 29 degrees.

The moon’s orbit around Earth is also slightly eccentric - at perigee (its closest distance to Earth), it’s a little over 362,500km from Earth, while at apogee (furthest from Earth), it is almost 405,500km away.

That might not sound like much - around a 10% variation in distance - but it means that the apparent size of the moon in the sky can vary quite markedly, as can be seen below.

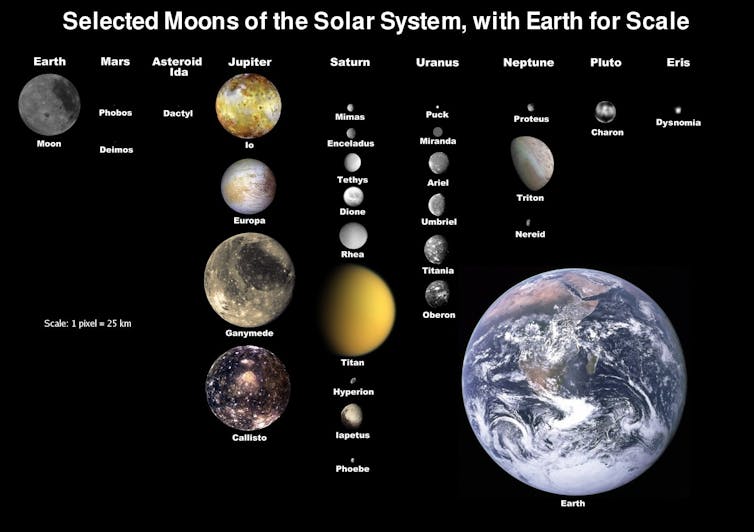

The moon is 1,737km in mean radius (compared to the Earth’s 6,371km), making it the fifth largest satellite in the solar system. But even though it is ¼ the diameter of Earth, it is significantly less dense than our planet (at roughly 1/81 the mass of Earth).

Even stranger is the fact that the near- and far-sides of the moon look so different. The near-side, familiar to anyone who has spent any time looking at the night sky, is dominated by the “mare”, basalt outpourings that span a large fraction of surface.

The far side of the moon, by contrast, looks totally different - a dichotomy that has long puzzled researchers (although a recent study may have come up with an explanation).

The strangest planetary satellite?

In the four centuries that have passed since the discovery of the Galilean satellites (the four moons of Jupiter), the number of satellites known through our solar system has grown to more than 170 moons. And it’s not just the planets that have been found to host companions: the solar system’s smaller bodies are also regularly accompanied by their own satellites.

The dwarf planet Pluto is now known to have at least five satellites, and companions abound in every population of solar system object we study.

While there are several satellites larger than our moon (Jupiter’s Ganymede, Callisto and Io; and Saturn’s Titan), those satellites are all dwarfed by their host planet. In stark contrast, when compared with Earth, the moon is huge.

The other large satellites in the solar system orbit their host planets almost perfectly in the plane of their equator. Yet our moon’s orbit is inclined by between 18 degrees and 28 degrees to our equator.

So why is our moon so unusual? Why is it so different to so many of the other satellites in the solar system? The answer lies in the moon’s origin - and that’s a story we’ll return to shortly.

This is the first part of our series on the moon. To read the other instalments, follow the links below:

Part Two: Crash – a-ah! Our moon has a history of violence

Part Three: Out on the pull: why the moon always shows its face

Part Four: With or without you: the role of the moon on life

Part Five: Satellite of love: our on-off relationship with the moon