We all know the internet has enabled the creation of digital worlds of multi-layered, interconnected online information. But who’s going to protect this information for current and future generations?

Online publishing is moving away from its embryonic phase - consisting mostly of electronic surrogates of paper or print artefacts - towards a new, fully-fledged networked information paradigm.

Traditional information forms such as encyclopedias and journals are morphing into dynamic, interactive digital objects. Most prominent among these is Wikipedia, the Web 2.0 flagship, which provides a mechanism for open, collaborative and dynamic information authoring and sharing, fostering the co-production of knowledge.

We’ve already seen a proliferation of free information services: Google Books, Google Maps, AustLII, and the ABS Database, to name just a few. Portals such as Health InCite open digital doorways to virtual meta-collections of specialised information.

And Britain’s largest non-governmental medical research funding body, the Wellcome Trust, is putting its weight behind the open access model by requiring grant holders to publish in free online journals.

Britannica’s demise

In this context, the recent demise of the print edition of Encyclopedia Britannica (EB) after 244 years of publishing could be painted as just another step in the inevitable move from a paper to a digital culture. But it also raises deeper, quite specific, concerns.

While early print editions of EB are still accessible to us today, it isn’t clear whether online archives of dynamic interactive digital publications such as EB will prove to be as robust over time. Will the interconnected online information we currently access still be accessible in 20 years - or 200?

Preservation professionals point to the frailties of the digital medium. In a 1995 Scientific American article, author Jeff Rothenberg summed it up pithily: “Digital data lasts forever or five years – whichever comes first”.

The role of public libraries

Libraries have always been repositories of our cultural memory and knowledge.

Since the dawn of online publishing, they have been more than simply preservers of physical artifacts; they have also been gateways to a world of subscriber-only journals and databases.

But, as we move further into the digital age, the relevance of libraries as intermediaries between information and the public is being questioned.

We are seeing a major shift away from the “user-pays” business model of online publishing towards the Google open-access model, supported by the advertising dollar and, from the user’s perspective, the exchange of personal and use-history data for free content.

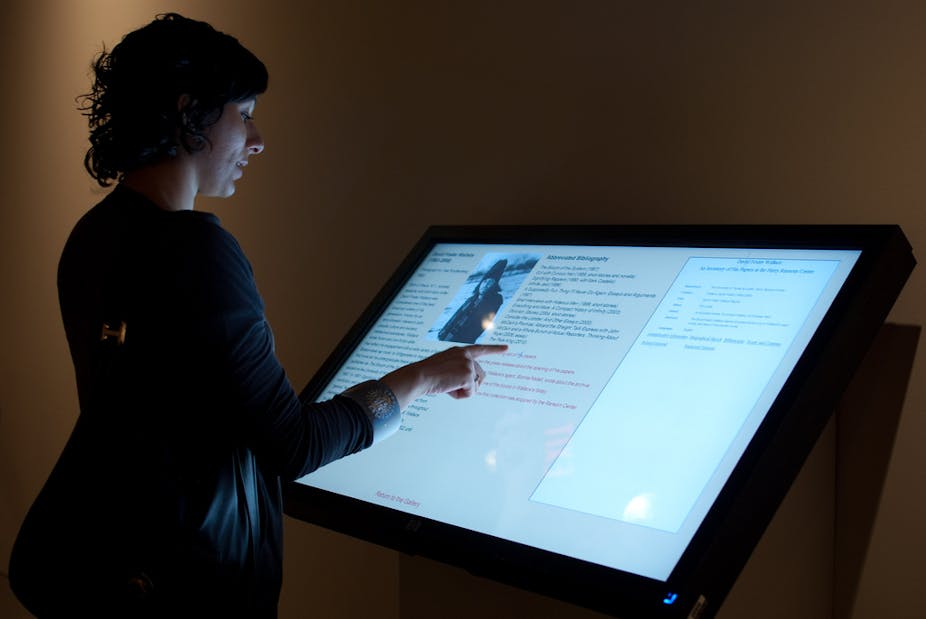

In response, libraries are transforming their intermediation services. Rather than merely controlling access to their own collections, they now play a vital role in guiding their user communities through the multiverse of online information.

But how well are they facing up to the challenges associated with archiving dynamic web knowledge and culture, as opposed to just navigating users through it?

The responses so far fall into two major categories. In collaboration with institutions such as the Library of Congress and the Smithsonian, the US based Internet Archive is attempting to “archive the whole web”.

The archive’s Wayback Machine was initially quite successful in preserving early websites and their interactive elements. Closer to home, the National Library of Australia’s Pandora archive of culturally significant websites has taken a more selective approach, freezing chosen websites at particular points in time.

With the web’s increasing size and complexity, though, much that is now being preserved through initiatives such as those outlined above comprises static digital snapshots.

Is the concept behind the Wayback Machine still feasible, whether applied selectively or across the board, in the context of increasingly complicated internet architecture? Can we find a way to peel back the layers of time so we can continue to truly interact with archived versions of our complex information multiverse?

As-yet-unknown digital preservation technologies may help us address this question, while raising several others, not least: who will provide these interactive archival services on the net and in the cloud?

Perhaps the business models of the open access movement can be applied to these ongoing archiving challenges. Or there may be commercial opportunities here for online information service providers. Developments in the hidden backrooms of Google and Facebook might be of relevance too.

A robust market may emerge for the provision of personal archiving services to the users of YouTube, Facebook and other social media who rely on those sites to preserve their memories.

But can these potential solutions survive beyond the life of their commercial providers? A recent example of the issue here came when the website Poetry.com was sold, and the archive of its 7m users was lost.

There is a place here for the great public library institutions of the world to work in partnership with commercial providers.

By providing trusted, sustainable archiving of dynamic web knowledge and culture, they can continue to fulfil their vital, ongoing societal role as protectors of our information heritage.