It’s not every day that you discover a huge structure that stretches more than half way across the sky. But this exact thing happened to the international team of astronomers I was leading, as we pored over observations taken with the CSIRO’s Parkes Radio Telescope recently.

What we have discovered are giant outflows of charged particles emanating from the central regions of our galaxy, as reported in our paper published in Nature earlier this month.

So where do these charged particles come from? And what can they tell us about our galaxy?

Cones and particles

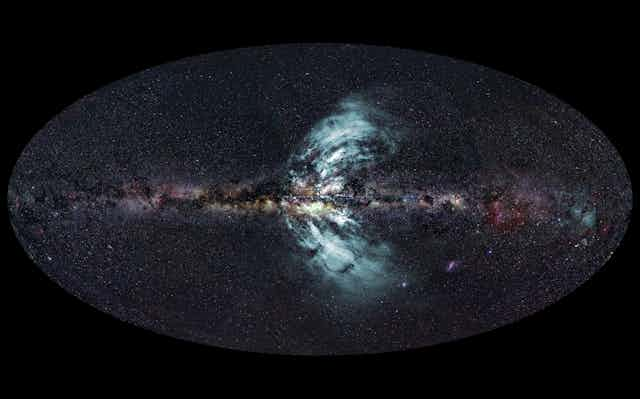

These outflows of charged particles consist of two lobes extending vertically from the disc plane of the galaxy on either side. Imagine two cones with their narrowest points joined together and you get an idea of what this structure looks like (see image above).

The lobes closely correspond to the gamma-ray bubbles discovered in 2010 using data from NASA’s gamma-ray space telescope Fermi (see image below).

These outflows are huge, stretching 120º across the sky – two-thirds of the way from horizon to horizon. In absolute terms, these outflows are spread across 50,000 light years – half the diameter of the entire galaxy. Quite simply, this is the largest structure ever discovered in our galaxy.

Origins

The analysis of the Parkes data shows these structures are outflows of charged particles generated by star formation activity in a narrow area around the galactic centre. The central part of the Milky Way contains a massive amount of star-forming gas and many young and massive stars which form and explode as supernovae.

The lobes also contain three ridge-like, parallel structures corkscrewing around the surface of the lobes. At least one of them looks to be connected back to the galactic centre and its footpoint might be one of the super-stellar clusters orbiting the Galactic centre.

The ridges, we suggest in our Nature paper, are direct outflows coming out from one of these individual super stellar clusters. The other two ridges are not connected back and their footpoints are no longer active.

These ridges might thus be relics of past star-formation activity – a signature of past stellar clusters orbiting the galactic centre.

Detecting the undetected

Many people ask us why these huge structures have not been seen before. This is because the sky was previously observed at a radio frequency that was either too low or too high.

At low frequency the signal is hidden because of a phenomenon called Faraday rotation – when the polarisation angle of light is rotated by material between the source and the observer. At high frequency the signal from the charged particle outflows is too weak and goes undetected.

When we planned our project we were aiming to study the structure of the galaxy and its magnetic field and we decided to observe at an intermediate frequency (2.3 GHz) to overcome the issues mentioned above and unveil the hidden galactic signal.

What has really surprised us is the massive amount of energy contained in the lobes – in the order of the energy expelled by a million supernovae.

To provide a bit of context, each supernova is so bright that it outshines the entire galaxy hosting it. The structure we discovered hosts more energy than is expelled by a million of these stellar explosions.

This massive amount of energy is produced in a compact region (about 600 light years across) at the very centre of our galaxy and is spat out vertically in the form of these outflows to the outskirts of the galaxy – the galactic halo.

This halo was thought to be a quiet place, but we now discover that it is continuously injected with a massive amount of energy. Our study would seem to suggest that the interaction between our Galaxy and its periphery needs to be rethought.

Our data also show that the outflows carry a strong magnetic field with a massive magnetic energy which is generated in the very centre of the galaxy and transported away in the halo.

We suspect this process can play a key role in generating and sustaining the galactic magnetic field, whose origin has been a mystery since its discovery.

How the outflow field we discovered connects to the general field of the galaxy will need to be investigated in future.