The world of political poetry has suffered some significant losses in recent months. Václav Havel, a poet long before he was the last president of Czechoslovakia and the first president of the Czech Republic, died in late December 2011.

Although many of Havel’s poems were whimsical “concrete” poems, a good number were pointedly critical of Czechoslovakian society and politics of the time. These works, along with his other dissident activities, landed him in jail from 1979 until 1984.

February this year saw the death of the Polish poet and Nobel laureate, Wislawa Szymborska, whose poems chronicled Polish history from WWII, through Stalinism and beyond. “My poems are strictly not political. They are more about people and life,” Szymborska once remarked, “but, of course, life crosses politics.”

Feminists – and certain political regimes – have long believed that the personal can be very political indeed. It’s a message reiterated by Adrienne Rich, one of America’s most influential contemporary poets, whose poetry books have sold close to a million copies.

As a woman and a lesbian of Jewish descent, Rich was concerned with the politics of identity long before the idea became de rigueur. Poetry is a map, she declares in her poem, “Dreamwood”: not a revolution, “but a way of knowing / why it must come”. Rich’s death on 27 March dispatched a wave of mourning around the world.

The marriage between poetry and politics has a long history. Archilochus wrote some of the earliest political poetry, and Horace’s tribute to Augustus’s principate in the Roman Odes is among the greatest political poetry ever written.

While much of the earliest political poetry was written in tribute to leaders, much of contemporary political poetry is written in protest.

Robert Hass, American poet laureate (1995-97), elucidates the contemporary view: “I think the job of poetry, its political job, is to refresh the idea of justice, which is going dead in us all the time.”

Nevertheless, political poetry can be difficult for the critic to esteem. Harold Bloom held it to the highest measure in his attack on The Best American Poetry 1996 anthology, edited by Adrienne Rich, calling it “a stuffed owl of bad verse”. He was unable, he claimed, to find in it more than an authentic poem or two.

“It is of a badness not to be believed, because it follows the criteria now operative: what matters most are the race, gender, sexual orientation, ethnic origin, and political purpose of the would-be poet. Sincerity, as the divine Oscar Wilde assured us, is not nearly enough to generate a poem.”

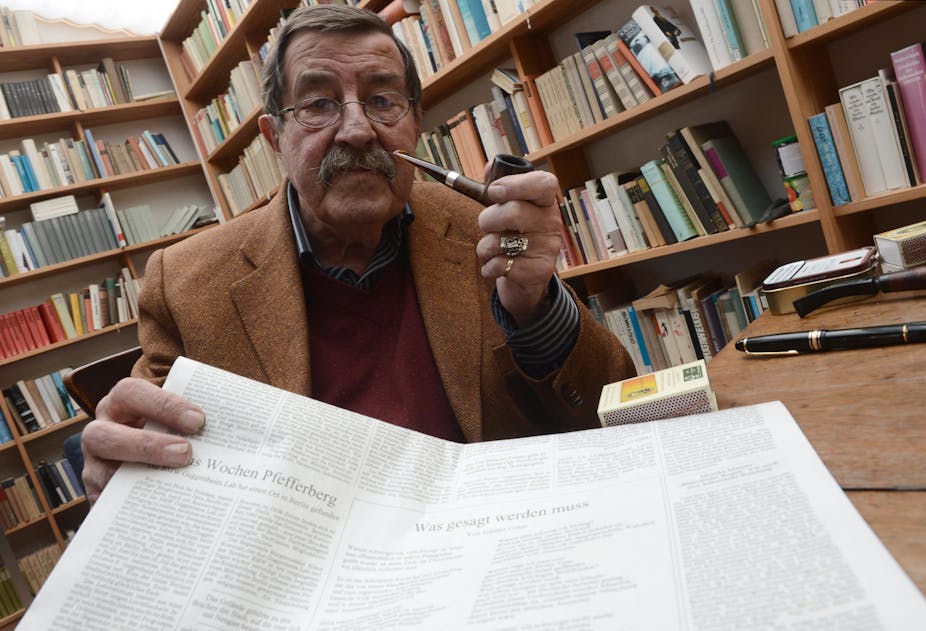

Yet sincerity is precisely the stuff of which Günter Grass’ incendiary poem, “What Must Be Said”, is made. The poem’s argument is two-fold. First, Israel’s nuclear arsenal is a threat to the Iranian people and “endangers an already fragile world peace”;

Second it argues why for a long time he has felt unable to voice his fears owing to a greater fear of being punished for the sins of his German forefathers:

“But why have I kept silent till now?

Because I thought my own origins,

tarnished by a stain that can never be removed,

meant I could not expect Israel, a land

to which I am, and always will be, attached,

to accept this open declaration of the truth.”

Despite his declared attachment to Israel, Grass was right to worry. The poem caused a tremendous ruckus when it appeared on 4 April in several European newspapers.

It demonstrated decisively that poetry can “make things happen” after all, on 8 April Israel declared Grass a persona non grata and denied him future entry into the country.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu said the poem’s allegation that Israel poses a greater threat to world security than Iran – “a regime which denies the Holocaust and calls for Israel’s destruction” – is a “shameful moral equivalence”.

Grass was quick to apologise for the wording in his poem: instead of saying Israel, he should have said “the Netanyahu government”.

Despite the brouhaha the poem has incited, most critics agree it isn’t particularly good. Heather Horn, who translated it from German, chided its “needlessly Teutonic constructions” and “winding and parenthetical tone”.

Someone once said publishing a poem is like throwing a feather off a cliff and waiting for the thud. In Grass’ case the feather turned out to be an elephant and he was standing under it.

The absurdity of fuss generated by an average-at-best poem would be amusing, were it not for the toll it appears to have taken on Grass’s health.

On Monday this week - two weeks after the poem’s publication - Grass was admitted with suspected heart problems to a hospital in Hamburg. “There’s no danger to his life,” his doctor said in a written statement, assuring the world that the 84 year-old poet would return home by “the end of the week at the latest.”

In some societies – past and, sadly, some present – poets pay with their lives for the gall of social critique.

Putting politics aside, let’s hope Günter Grass’s price will not be so costly.