Sharing is a good thing right? We are told it is good for the environment by cutting waste and needless consumption; we encourage it in our children for their moral growth; we see it used in advertising, and when we think of it as a neighbourhood activity we get a warm and fuzzy glow. But how many people actually go and ask a neighbour for that fabled cup of sugar?

I recently received a “community cake” from a friend. “You’re into sharing with neighbours Millie,” she said, “I’ve got you the perfect present.” I was given a cake tin containing a recipe and all the necessary ingredients for making a cake. All the ingredients except for, you guessed it, a cup of sugar. That is where the community comes in; it was my challenge to go and introduce myself to an unknown neighbour and ask for a cup of sugar.

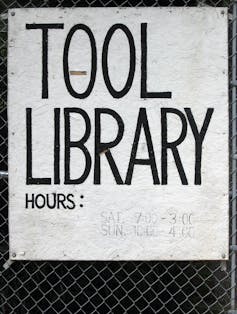

She gave me the cake because I’m interested in how or if ordinary Australians living in the suburbs share sugar, mix masters, lawn mowers, and other everyday stuff. My PhD explores what it means to share in suburban Australia. My research involves talking to people who are in organised sharing networks as well as those who are not.

References to that ubiquitous cup of sugar are frequent during research conversations. Many research participants talked nostalgically of the past when a neighbour would think nothing of asking a small favour. Conjuring a time, imagined or otherwise, when people were less lonely, communities more engaged, and consumerism somewhat more restrained. Indeed sharing was seen as a simple solution to the many social and environmental problems facing Australian suburbs.

It is not only my research participants who view sharing with somewhat rose-tinted glasses. Sharing, or what has recently been dubbed as “collaborative consumption”, is often presented as being a panacea for a plethora of social and environmental ills. A recent Grattan Institute report, Social Cities, outlines worrying signs about the increase in social isolation and loneliness in Australian cities.

Sharing household resources is listed in the appendix to the report, “ideas for social connection in cities”, as a cost effective way to address declining community connection. Not only viewed as a solution to social problems, sharing, or collaborative consumption, made it into the Top Ten Green Stories of 2010 in Time Magazine, in which sharing is considered as “one of the most heartening environmental trends”. Carpooling is a classic example where sharing is promoted as being an opportunity to get to know your community and help the environment.

Environmentalist Ted Trainer suggests that “we must share more things” in his paper The Simpler Way: An outline of the global situation, the sustainable alternative society, and the transition to it, and his call is supported by environmental groups. The Australian Conservation Foundation and the Alternative Technology Association encourage organised sharing through articles such as ‘Collaborative Consumption: give a little, take a little’ and ‘Join the freecycling Sharehood’ in which online sharing networks such as The Sharehood and Friends With Things are promoted. These websites facilitate the exchange of goods and services and aim to build “sustainable and resilient communities”.

The idea of Sharehood has been enthusiastically received by suburban residents with many people signing up as members, yet very few go on to utilise the network. The media has also enthusiastically picked up the concept, yet my research suggests not much actually gets shared. This is interesting given the perception of sharing as the “right thing to do” was common across those involved in the Sharehood, as well as those who were not. And most interesting of all, neither group shared more or less than the other.

So why are local neighbourhood sharing networks failing? With so many people willing to share items, generously posting offers to fix computers, lend wheelbarrows, and teach singing, what could possibly be going wrong?

The problem is in our definition of sharing. In practice, sharing is considered to be an act of generosity, rather than the common use or ownership of goods, time, or experience. We are taught as children that sharing is about being generous. Recently Play School changed the story of the Little Red Hen. In the original the little red hen asks the farm animals to help make her bread. They all refuse to help but want to share in the eating and the little red hen refuses. In the new version, the hen agrees to share her bread. When I asked Play School their reasons for changing the story they emailed back, saying:

We felt it was more in keeping with the ideas of generosity and sharing (which the program frequently models), in hand with a commitment to share in the work next time …

So sharing is promoted as being generous and, as it turns out while we’re really good at offering things and favours, we’re terrible at receiving. Research participants highlight this: “I’ll be damned if I’d ask”, “I wouldn’t want to impose” and, “I’ve got everything I already need” were common in discussions of sharing.

Although there are examples where sharing between neighbours is successful, both within my study and in the studies of others, it seems that this is the exception rather than the rule.

So what does this mean for programs aiming to encourage sharing?

Firstly, we cannot underestimate the cultural power of our need to be self-sufficient and to remain obligation free. As Robert Menzies proclaimed in his 1942 speech, The Forgotten People:

My home is where my wife and children are … the instinct to give them a chance in life – to make them not leaners but lifters – is a noble instinct.

For some, the request for a cup of sugar, a ladder, or advice about pumpkins, is an acknowledgement of an inability to cope on one’s own. No one wants to be seen as needy or not pulling their weight.

Giving is promoted as being ideologically and morally sound. We are constantly being reminded to give more and take less, yet perhaps we forget that to receive can be an act of giving. As one research participant said: “to learn to receive with an open heart may be one of the most difficult things”, yet I believe it may also be one of the most effective methods of community development.

The second thing to remember in our quest to increase neighbourly sharing is the value placed on privacy. With increasingly busy lives the desire to maintain the home as a private space is integral to the maintenance of the great Australian Dream. In many research conversations, people noted the paradox in their desire to be more neighbourly and engaged, yet at the same time wanting to avoid being drawn in to local networks of obligation. To ask a neighbour for something today, means tomorrow - perhaps at your inconvenience - the obligation must be repaid.

In mustering my courage to seek a cup of sugar for my community cake, I must, according to Menzies, become a “leaner”. Yet, what my study seems to show is that rather than being a burden, the very act of asking a neighbour for assistance is a generous act as it opens up the social landscape of acceptable community behaviour.

Neighbours get your cups ready!

Comments welcome below.