Last week, I received an email with the subject line: “Bravery award for baby killer.”

It urged readers to sign a Change.org petition calling on the Royal Humane Society of Australia to rescind a bravery award. Paul McCuskey, a volunteer firefighter, had been given a “Certificate of Merit” for helping to save the life of an elderly woman during the Black Saturday bushfires.

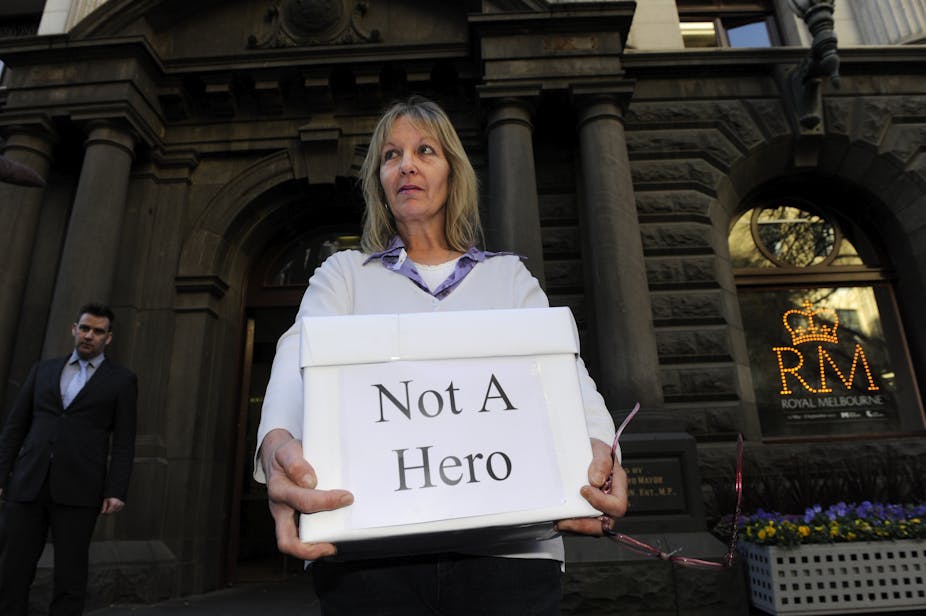

Yet McCuskey is now in prison for a series of vicious assaults on his partner Jeannie Blackburn - attacks that caused a miscarriage and left her blind in one eye. In the face of 18,000 petition signatures and calls from Humane Society patron Governor-General Quentin Bryce and the remarkably courageous Ms. Blackburn herself, the Society finally withdrew the award.

It’s a tragic case, and one that, as Suzy Freeman-Greene points out, raises complex issues. But whether you think websites like Change.org, GetUp! and All Out are genuine forces for progress or mere conduits for feel-good “slacktivism”, complexity is not something they are set up to handle well. Like their ideological opposite numbers in talkback radio, they need to present clear-cut narratives of right and wrong, with an unambiguous call-to-action at the end.

Yet these issues are unavoidably complex. In fact, the language we saw last week involved a clash between two ancient, competing understandings of morality.

The Humane Society’s objective is “to give public recognition to acts of bravery by bestowing awards on those who risk their own lives in saving or attempting to save the lives of others”. The emphasis here is focused on the moral quality of particular actions. It could be maintained – as the society reportedly initially did – that McCuskey’s actions on Black Saturday were morally praiseworthy, whatever else he’s done. But this way of thinking can easily lead to a sort of ethically crude arithmetic, as if we’re supposed to weigh rights against wrongs and come out with an overall score.

Much of the anger directed at the Humane Society’s decision to award the certificate in the first place, on the other hand, used a very different type of moral language: not evaluation of the action, but evaluation of the agent. Awards, we’re told, are for heroes - and a man who beats his partner cannot be a hero.

This focus on character belongs to the “virtue ethics” tradition that goes back to Aristotle. Virtues, according to Aristotle, are a job lot: you can’t be a generous thief or an honest glutton, because your vices will eventually disrupt and defeat your virtues.

But moral heroes often turn out to be flawed. Oskar Schindler, for instance, saved thousands of lives yet was unfaithful to his wife.

Even more troubling are the monsters who seem distressingly normal in other contexts. We find Stalin warmly addressing his daughter as “my little sparrow, my great joy” or tucking Beria’s children into bed disturbingly humanising, as if these scenes somehow mitigate his crimes. Or perhaps it actually makes him more monstrous somehow.

So, what should the Humane Society have done?

Let’s go back a step. Why do we have bravery awards? Not because we want to reward the virtue of courage per se, nor because we want to reward people for saving lives; otherwise every skydiver and surgeon would get one.

Rather, we give such awards in the aftermath of crises where the value and meaning of human life has nearly been obliterated by the absurdity of senseless, arbitrary destruction.

We reward those who hold that threat back, who in risking their own lives testify to the depth of the ways in which we value each other and thereby keep the moral sphere from coming apart. In chaotic moments that threaten to engulf us in meaninglessness, those who perform such acts keep the fabric of our moral universe temporarily intact.

You might say that a violent person can still perform such an act. But the “domestic” in “domestic violence” doesn’t just refer to a location, and the evil of domestic violence is not simply in the horrific physical and psychological harm it causes.

To understand the scale of its moral obscenity we must appreciate the depth of what it violates: the web of vulnerability, love, trust and security that unites us to those we live in the greatest intimacy with. An assault on the people given to us to love unconditionally shatters the moral sense and meaning of our most vital relationships. It is not simply violence in the home, but violence against the home, with everything that “home” implies.

Domestic violence is therefore more than violence: it’s a treason against the moral sphere itself.

To award someone for preserving the moral sphere who had also betrayed it in such a repugnant way would have been perverse.

Grappling with questions like this is hard work. It takes patience, an openness to dialogue and a certain degree of humility. But when our main avenues for talking about these issues are through soundbites and tweets, those virtues can be in short supply.

Online petitions are great - I’ve signed quite a few myself. But let’s not pretend we can just click our way out of moral perplexity.