The most recent Australian anti-obesity measure, the West Australian LiveLighter campaign, features a series of shocking television advertisements, including one showing a middle-aged man in his kitchen.

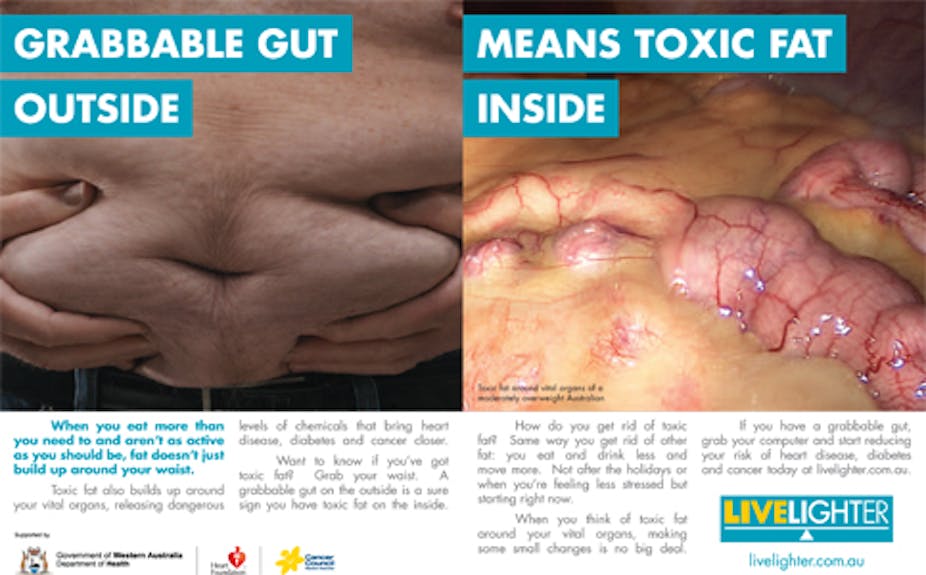

The man reaches into his fridge to take out a slice of left-over pizza. As he holds the pizza, wondering whether to go ahead and wolf it down, he glances down at his belly. His other hand squeezes the flesh there and the camera suddenly swoops into the man’s insides. Viewers are treated to images of pulsing slabs of bright yellow fat covering body organs.

The camera goes back to the man as he looks pensively through a doorway at his young sons happily playing a computer game. The voice-over says, “Fat around your waist is bad, but toxic fat around your vital organs is worse.”

The viewer is left in suspense, wondering if this dad will let himself and his family down by indulging his desire for pizza and thereby adding to his “toxic” visceral fat.

This is part of yet another in a series of social marketing campaigns conducted for health promotion purposes and funded by public health authorities. Like many such ads, it seeks to achieve behaviour change by evoking negative emotions. These include fear of disease and an early death, guilt, shame, embarrassment – and in cases such as this one, disgust.

The images of this ad share the “yuck factor” with past Australian anti-smoking campaigns and photographs on cigarette packets. These images have featured gangrenous limbs or digits, blackened lungs full of tar, a mouth disfigured by cancerous lesions, people coughing up blood and so on.

The LiveLighter campaign is replicating the “Every cigarette is doing you damage” anti-smoking campaign by focusing on internal organs contaminated and rotted by tobacco. Here the slice of pizza replaces the cigarette as the poisonous agent of bodily damage.

The health authorities that give the go-ahead to advertising agencies to create such ads clearly believe that provoking shock, horror and repulsion in the viewer is a legitimate and effective means of persuading people to change their habits.

In the case of the LiveLighter campaign, the intention is clearly to invite the target audience – people who have a “grabbable gut”, as the campaign’s print media ads put it – to envisage the insides of their bodies as diseased, poisoned and repulsively overrun with deposits of viscous fat. As it’s noted on the campaign website: “We certainly hope to make a big impact with this new campaign.”

The campaign can be criticised for its very imprecise use of language with such terms as “grabbable gut” as a marker for dangerous weight-gain, and its simplistic representation of internal fat as invariably “toxic”.

Critics of these kinds of tactics in health social marketing campaigns are less than convinced that they are ethical or even effective. They have expressed strong concern that the association of certain types of people with revolting images serves only to position these people as disgusting themselves. And looking at these images of chunky fat strangling body organs is enough to put anyone off their pizza – or their low-calorie salad, for that matter.

The idea that this apparently poisonous stuff is bubbling away inside one’s body inspires revulsion towards that body – both its outward “grabbable” fat and its internal hidden “toxic” fat.

Do such disgust-inducing tactics even work to change people’s behaviour? It’s one thing to arouse controversy by using shock tactics, it is another for such tactics to actually have an effect on entrenched daily habits. Research suggests that although anti-obesity campaigns are certainly capable of drawing audiences’ attention to the issues, and sometimes in inducing them to make short-term changes, they have not often been effective in changing long-term behaviour.

Some researchers have argued that fear tactics may be counter-productive, as they simply encourage people to switch off and not pay attention to campaign messages. Even if fear is induced, if people feel unable to make changes this may lead to unresolved insecurity, anxiety and self-hatred.

While little focused research has zeroed in on evaluating specifically the effectiveness of attempts to induce disgust, it’s likely that many members of the target audience may simply avert their eyes because they find the images so repulsive. The whole emotional reaction of disgust is about aversion, the desire to avoid the sight, smell or touch of the repellent object with which one is confronted. Moral meanings are also central to what we find disgusting.

Whether or not they are effective, it’s difficult not to feel queasy about the punitive, patronising and moralistic attitudes displayed in these kinds of anti-obesity campaigns. In their efforts to inspire negative emotional responses, the agencies that develop and fund such campaigns never appear to acknowledge or take responsibility for their possible unintended side-effects. These may include provoking and perpetuating self-disgust, guilt, shame and dread and contributing to the marginalisation and stigmatisation of certain behaviours, body types or social groups.